The End at Stalingrad: 20th January – 2nd February 1943

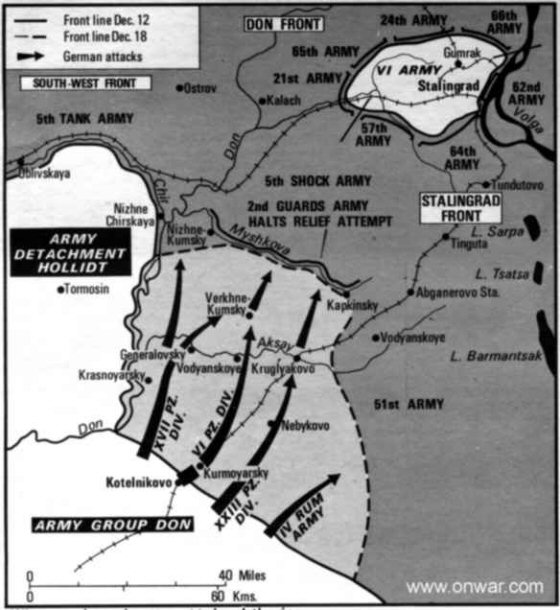

Hitler could now plan a relief effort to break the Soviet ring around Stalingrad. Fall Wintergwitter, Operation Winter Storm began on the 12th December 1942. General Hermann Hoth had the LVII Panzer Corps under his command and, in the driving blizzards the Whermacht undertook its first winter offensive. Despite good headway, the Soviets were able to halt Hoth on the Myshkova River, some 30 miles south west of the Kessel. Within Stalingrad Paulus refused to breakout as this would have meant refusing a direct order from Hitler. Field Marshal von Manstein repeatedly urged Paulus to manoeuvre 6th Army to break out and initiate Operation Thunderclap, the plan to link up 6th Army with LVII Panzer Corps. Paulus refused and when the Russians launched Little Saturn on the 16th December 1943, the fate of 6th Army was finally sealed. Further Soviet formations had crushed their way through Italian and Romanian positions on the Don heading towards Millerovo. The only link the 6th Army had to the outside world was via the tenuous air bridge that, as the Luftwaffe generals feared, could not adequately supply an army so big.

{default}

Operation Winterstorn

THE END AT STALINGRAD

The soldiers of the divisions that made up 6th Army were not aware of their ultimate fate for a while. Many of them put great stock in the Fuhrers promise of relief. Indeed, many inside the pocket could not, or rather would not believe that a whole army of 250,000 men would be left to wither on the vine and die, as the Fuhrer said, "you can rely on me with rocklike confidence." Initially the Russian formations around Stalingrad were content to sit and wait. As the German frontline was gradually being pushed westwards there was no rush to eliminate the Kessel. Once the prospect of relief had disappeared, the Soviets had time and hunger on their side.

Food was the biggest concern inside the Kessel. Intense and very strict rationing had been out in place under the orders of the 6th Army’s chief of staff, Major General Schmidt. Supplies that were flown in were in no way adequate with the figures been flown in far from the required amount, only once did the figure ever reach 300 tons. Furthermore, the Luftwaffe transport fleet was taking heavy casualties, and due to the Russian offensive was forced to fly from bases further and further to the west. Inside Stalingrad the issue of bread had fallen to 100 grams per man. The only meat most soldiers had to eat was horse meat or, if they were lucky, whatever meat they could plunder from a canister dropped by the Luftwaffe. This offence, looting, was punishable by death, and so was hoarding. This, however did not stop over zealous quartermasters from amassing quantities of supplies in well furnished and stocked bunkers to the rear while the soldier on the frontline froze whilst munching a mouldy slice of bread.

The situation for the wounded was terrifying. The field hospital at Gumrak was over crowded and the medical officers performed under ghoulish conditions. The weather was cold and many patients froze to death awaiting treatment. Medical supplies were in extremely short supply. Wounds that under normal conditions would have been treated fairly quickly usually killed a man. There was little possibility for a wounded man to be airlifted out of the Kessel, though a fair few men were able to leave Stalingrad in this way. The cases of self inflicted wounds rose dramatically, an offence that was punished by posting to a penal detachment or by shooting. Many historians and survivors describe chaotic scenes at Gumrak airfield as throngs of men, wounded soldiers, staff officers, and deserters tried to get a valuable seat on a outgoing JU 52. As reality dawned on the men inside the pocket, chaos began to descend and discipline was in danger of collapsing.

JU52s Supplying Stalingrad