The End at Stalingrad: 20th January – 2nd February 1943

BACKGROUND

Following the halting of the Soviet winter counter-offensive in March 1942, Hitler pondered where to strike in the East. Operation Barbarossa and the subsequent defensive battles had robbed the Whermacht of its ability to launch an offensive running the length of the Front as it had done in June 1941. Leningrad was an option, and indeed serious preparations were being made with Von Manstein’s 11th Army to be transferred to Army Group North from the Crimea after the subjugation of Sebastopol. Army Group Centre was still in a position to strike at Moscow from its positions at Vyazma and Rzhev. But it was in the South that Hitler had decided to strike.

As ever economic considerations precipitated Hitler’s strategic thinking, as it had earlier in the campaign with the diversion of Guedrian’s armour into the Ukraine when the road to Moscow lay seemingly open. The capture of the oil rich fields of the Caucuses would in Hitler’s belief fuel his drive to victory and deal the Soviets a blow they could not recover from. Furthermore the successful German counter attack against the Soviet thrust to capture Kharkov had left the Germans with good jumping off points for an offensive across the Donets. Operation Brunswick, a much amended directive that had its strategic objectives widened during the course of the campaign, was the code name given to Germany’s 1942 summer offensive. The objectives were the Caucuses and their oil, and the River Volga; this second objective was designed to cut off Soviet North-South communications and supplies, especially up the wide Volga. Stalingrad itself only became a major objective when Operation Blue arose out off Fuehrer Directive Number 45. This widening of objectives spread the German troops thinly on the ground, as such the Army Groups allocated to the offensive had a large number of Axis satellite troops allocated to them; these were often deployed on the flanks of the German schwerepunkte, a decision that would have cataclysmic consequences later in the campaign.

{default}Sixth Army, under the general command of General der Panzertruppen Fredrich Paulus, was given the task to spearhead the advance across the Don steppe and up to the Volga and beyond. 4th Panzer Army (Hoth) would provide the mechanized and armoured punch for the 6th Army, which at the time was the most powerful single formation in the entire Whermacht. In a classic Blitzkrieg campaign 6th Army was in a position to start assaulting the city of Stalingrad by early September, 16th Panzer Division had reached the Volga in late August. Once inside the city progress was slow but by 30th September the Soviet 62nd Army, under General Chuikov, had lost the southern part of the city and only held fast in the Factory District in the North.

Street Fighting in Stalingrad

The fighting in Stalingrad was very bitter with house to house engagements and close combat by small sized units and assault companies. The Germans advantage in numbers was balanced by the Russians ability in urban combat and the advantages defensive fighting in a city provided. However, despite rugged Russian efforts Paulus was ready to launch his last, and he was confident that it would be the decisive, assault on the 11th November, his regiments having being reinforced by specialist assault teams comprised of engineers that had been specially flown in.

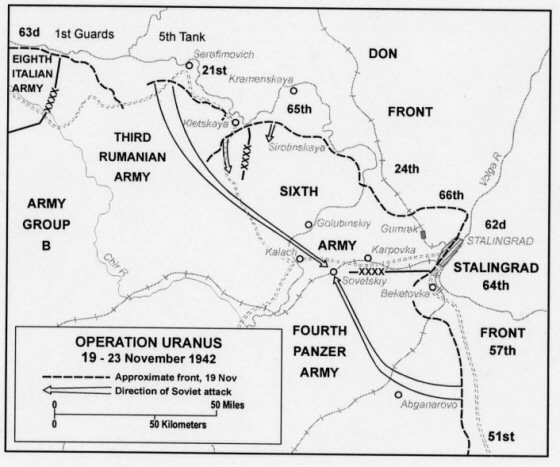

THE TRAP ? OPERATION URANUS 19TH NOVEMBER 1942

STAVKA had been eyeing the extended German flank for a while. While German strength was being frittered away in the city, the Russians had begun a steady and very secret build up of troops on either flank of the beleaguered city. To the North of Stalingrad the Romanian 3rd Army held a long front on the River Don, while to the south the Romanian Fourth Army safeguarded 6th Army from attack. When the Soviet attack came it took the Axis forces completely by surprise. Earlier attempts at trying to force the left flank had failed, but these had been rapidly and ill prepared at the behest of Stalin, eager for a counter-stroke. This time however, it was Marshal Zuhkov, who had saved Moscow the previous winter, who had planned the operation.

Operation Uranus