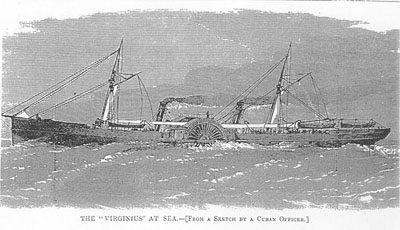

The Virginius

Unsaid, another motive for Grant was likely the hope that Santo Domingo would divert attention from the growing scandals plaguing his administration. But he managed the project poorly. The Senate, offended by the president’s heavy-handed and secret maneuvering in the matter, withheld support. And, like the public at large, most Senators were more interested in Cuba. Concern over Cuba and whether America would get drawn into the island’s conflict had many Senators wondering if Grant were not biting off more than he could chew in the Caribbean.

Conceding defeat, Grant turned his focus to Cuba and instructed his secretary of war, John Rawlins, to commence secret negotiations with Spain. The Spanish government seemed amenable to a deal. Its president at the time, General Juan Prim, worried about his country’s ability to maintain control over what had become an increasingly renegade colony. He offered to sell the island to Cubans, with the United States holding the mortgage. But before the deal could be struck, Spanish nationalists, trying to hold on to a vestige of the Old World Empire, assassinated Prim. About the same time, Rawlins died, and with him any impetus for U.S. intervention into Cuba.

{default}At the time, American Secretary of State Hamilton Fish felt relief. He logically believed that the United States, still recovering from its own civil war, had no taste for another. He had consistently resisted efforts to become entangled in Cuba, arguing against aid for Cuban insurgents and U.S. official recognition of the Cuban belligerency. Now, all his efforts seemed wasted as the Virginius resurrected talk of U.S. involvement.

Fry was smart enough to know he was in a tough spot. The United States was officially neutral in the Cuban dispute, and filibustering was illegal. More importantly the Virginius’ American registry was invalid. She had no right to fly the American flag given her ownership by the Cuban Junta. Worse, General Juan Burriel, the governor of Santiago, the capital of the island, hated the Cuban rebels and the United States. Burriel personified Spanish cruelty. If Fry expected mercy here, he would soon get an education.

Anxious to extract a measure of revenge against the Cuban guerillas, and in the bargain hoping to set an example for anyone helping their cause, Burriel moved with dispatch. He ignored a 1795 treaty with the United States that ostensibly guaranteed Americans the right to a civil trial. Instead, Burriel conducted a secret military trail of the prisoners that denied them the benefit of counsel. The fate of Ryan and three Cubans seemed inevitable. They had been sentenced to death three years earlier for prior indiscretions.

The newly formed Spanish government was three thousand miles away. Just five years removed from a monarchy, it was now a republic headed by President Emilio Castelar. On learning of the seizure, Castelar immediately cabled General Joaguin Jovellar, the chief Spanish military official in Cuba. With no desire to provoke the United States, Castelar cabled Jovellar to release the crew of the seized vessel. Unfortunately, Jovellar was in Havana with no easy means to communicate with Burriel in Santiago. Ironically, Cuban rebels had severed telegraph lines between the two cities. In any case, Burriel likely would have ignored orders to act with leniency.

Eight days after the ship’s seizure the New York Times reported the first executions—four days earlier Ryan and three others had faced a Volunteer firing squad. The United States state department had tried to intervene, first through its consulate on the scene and next by instructing its foreign minister to Spain, former Civil War general Daniel Sickles, to demand that the Spanish government delay extraction of any penalty on the prisoners until more could be known of the incident.

“The four prisoners were shot at the place made famous by previous executions, and in the usual manner, kneeling close to the slaughter house wall,†the Times reported. “All marked the spot with firmness.†Of Ryan, an eyewitness said the man “showed marked courage,†and that he “kept up to the last, never flinched a moment, and died without regret.†The New York Herald covered the more gruesome details. Its reporter George Sherman had attempted to sketch the scene but was arrested. He would spend three and half days in a noisy jail for his effort.

News of the executions angered New York City residents. Cuban sympathizers held mass rallies demanding that Grant do something. On the surface, the president was uncharacteristically calm. Behind the scene, he instructed Fish to commence diplomatic discussions with the government in Madrid. He also authorized the U.S. navy to make preparations to sail to Cuba in the event diplomacy failed.

Had the executions stopped at the first four, the crisis might have passed with little fanfare, but four days later the nation learned that Captain Fry and forty-eight other men had also been brutally shot. One accounting of that crime described the scene. "The Spanish butchers advanced to where the wounded lay writhing in agony, and placing the muzzles of their guns in some instances in the mouths of their victims, pulled the triggers, shattering their heads into fragments.â€

A poignant farewell letter Fry penned the night before to his wife made its way into the American papers. “When I left you I had no idea that we should never meet again in this world, but it seems to me that I should tonight, and on Annie’s birthday, be calmly seated, on a beautiful moonlight night, in a most beautiful bay in Cuba, to take my last leave of you my own star, sweat wife! And with the thought of your own bitter anguish, my only regret of leaving.â€

Through inexcusable to civilized minds, Burriel’s action typified how Spanish authorities operated in Cuba. In a similar atrocity that same day they murdered eighty other insurrectionists in cold blood.

British citizens had also comprised part of the crew and had been shot. That evening the British warship, Niobe, arrived from Jamaica and leveled its cannon on the city. Discretion being the better part of valor, Burriel wisely ended further bloodshed.

[continued on next page]