The Virginius

Now the second act. The officer turned to Ryan and Cuban general Bernado Varona. When ordered to assume the same position, they hesitated. Whether through fear or defiance, neither prisoner obeyed and soldiers again intervened. Proud military men, Ryan and Varona struggled to their feet and asked to die standing like men. The impatient officer shouted to his executioners, who felled the victims where they stood. One witness would later call the shooters “wretched marksmen,†as Ryan still lived, moaning in agony.

{default}The officer stepped forward brandishing his sword. Perhaps he cursed, and surely he sneered in contempt before thrusting the blade through the wounded man’s heart to finish the job. And in cruel testimony to the hatred that this Spaniard felt for his enemies, he next waved to a group of cavalrymen awaiting his signal. The riders spurred their mounts forward and thundered back and forth over the bleeding corpses, grinding them to mush.

Not to be left out, the aroused crowd of civilians, so far denied its own hand in the affair, now surged forward, intent on ugly work. Some men held machetes. They savagely severed the heads from the bodies, and affixing the four prizes to long pikes, led the crowd on a triumphant march through the Santiago streets, gleefully exclaiming victory over the insurgents and foreigners. The celebration had begun. It was November 1873.

The day’s butchery would ignite an international crisis that challenged American president Ulysses S. Grant and almost threw the United States into war with Spain. The event that sparked the crisis was a seemingly innocuous seizure by Spain of a ship in Caribbean waters, the Virginius. The vessel was a filibuster; according to international sea law it operated illegally, running guns and supplies to Cuban rebels engaged in a ten-year fight for independence against the oppressive Spanish government on the island—not really the business of the U.S. Government. Had that been the whole story, the incident would have likely died on the back pages of the papers. But because the Virginius was flying the U.S. colors, President Grant couldn’t so easily ignore the matter. Nor were strong forces in Washington and New York about to let him.

Many Americans, given their own history, sympathized with the plight of the natives in the Spanish colony. The European nation ruled the island with an iron fist, and slavery, so recently eradicated in the United States in a bloody civil war, was still openly practiced there. The American press had covered the war since its inception in 1868, fueling readers’ passions with graphic coverage of massacres against Cuban women and children, a commonplace event in the island struggle. The savage character of the fighting appalled the American public. When news of how Spanish authorities had treated the ship’s crew, American concern grew to outrage.

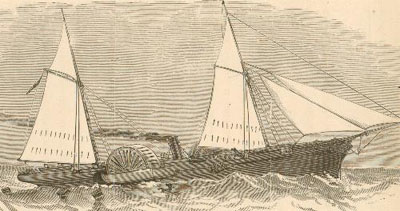

Four days before Ryan’s execution, Captain Joseph Fry, an Annapolis graduate, stood on the deck of the Virginius. So far so good. A side-wheeler capable of eight knots, the Virginius was making good time. Having embarked from Jamaica that morning, Fry was on schedule to unload his cargo as planned. In another two hours he would anchor in a secluded spot off the coast of Cuba. Fry had piloted the ship before on similar missions. As then, expatriates and American sympathizers in New York, known as the Cuban Junta, had financed the trip.

Among his passengers were Cuban General Oscar Varona and William Ryan, a Canadian soldier of fortune. Together they commanded more than one hundred rebels hoping to join their compatriots in the mountains of eastern Cuba. Fry’s cargo included some five hundred Remington rifles, swords, revolvers, and ammunition.

Along with its renegade crew the ship carried a notorious reputation. As a Confederate vessel during the American Civil War it had slipped the Union blockade between Mobile, Alabama and Havana. For the last several years it had pirated arms to Cuban rebels, prompting the Spanish government to complain to Washington. The Volunteers—the name given pro-Spain elements on the island, including Spanish military forces hostile to native Cubans—considered the Virginius a nuisance. They were anxious to get their hands on her.

Twenty miles off the Cuban coast, Fry suddenly spotted smoke on the horizon. The Spanish warship, Tornado, another former Confederate ship, was heading in his direction. Fry quickly reversed course and ordered a retreat to Jamaica, a British protectorate. A ten-hour chase ensued. The Tornado, the quicker of the two ships, caught Fry while still outside British waters and fired a warning shot across the Virginius’ bow. Now desperate, Fry ordered his crew to toss his contraband cargo of arms overboard. A second cannon shot found its mark, shattering the ship’s smokestack. The captain reluctantly hove to and surrendered his ship.

Though they did not know it, the crew of the Virginius was a victim of bad timing. For the last three years Grant had been working to expand American influence in the Caribbean. His primary objective had been to secure Santo Domingo through annexation, it being the only independent state in the West Indian islands. Encouraged by land speculators and the Navy, Grant considered it a land ripe with minerals and one in need of salvation. Like its neighbor Cuba, Santo Domingo had a history of internal revolution. The island could provide the nation a key naval base and extend the principal of the Monroe Doctrine.

[continued on next page]