Was Winston Churchill to Blame for the Fall of Singapore?

British officers surrender to Japanese troops at Singapore, Feb. 15, 1942.

"I put the telephone down. I was thankful to be alone. In all the war I never received a more direct shock," British Prime Minister Winston Churchill said. He had just received word Japanese naval aircraft had sunk two British warships off the coast of Malaya on December 10, 1941. The prime minister was to receive many more shocks over the next two months, culminating with the fall of Singapore on February 15, 1942. He had spoken of "Fortress Singapore," but it had not held out for long. Was Churchill responsible for Singapore’s surrender?

{default}Great Britain recognized Japan as the main threat to Singapore as far back as the end of the First World War and had made plans in the event of war. A strong British fleet would sail to Singapore to seize control of the seas around it, preventing a direct land invasion of the colony or on the Malay Peninsula just to the north.

Churchill gave assurances early in the war to both Australia and New Zealand that defending Singapore would take precedence over British defense of the Mediterranean. But late 1941 found Britain in a fight for its life in a war against both Germany and Italy. Singapore did not receive what was planned or was promised. It got what could be spared, a squadron known as Force Z.

Force Z consisted of the most recently constructed capital ship in the British Navy, the battleship Prince of Wales, accompanied by the battle cruiser Repulse, and four destroyers, all commanded by the 5’2" Admiral Sir Tom Phillips. The aircraft carrier Indomitable was also to be part of the force, but it was undergoing repairs after running aground near Jamaica. With his "fleet" lacking an aircraft carrier, Phillips anticipated air cover from the Royal Air Force flying out of Singapore and sailed from there on December 8th—too late to disrupt Japanese landings on the east coast of the Malay Peninsula that same day.

Air cover for Force Z was not forthcoming, but Phillips sailed on after receiving news of a second Japanese landing near his position. He maintained radio silence, hoping that stealth, maneuver, and anti-aircraft fire would ensure his ships’ survivability, but a Japanese submarine reported their position. On December 10th, over 100 Japanese level bombers and 25 torpedo bombers struck. The Repulse went beneath the waves with a third of her crew; Prince of Wales sank soon after, losing one-fourth of her sailors—the first capital ships ever sunk at sea in wartime by aircraft. Phillips drowned. Force Z, however brave its commander and crews, was simply too small to carry out the naval portion of Britain’s defense strategy for Singapore. Nor would have adding a British aircraft carrier such as HMS Indomitable equipped with only a handful of modern fighters likely have made any difference against such a large aerial force.

British air power might have filled the vacuum left by the lack of a strong fleet. British planners recommended reinforcing Singapore with hundreds of up-to-date aircraft. But Singapore fielded mostly obsolete fighter types such as Brewster Buffaloes. Once again, defending Singapore was less of a priority than defeating Germany, even if defeating Germany meant shipping hundreds of modern Britain fighters to the Soviet Union or retaining them for its own forces in the Middle East.

The third element in British strategy was a quick strike into southern Siam (now Thailand) to seize airfields and landing areas that could be used by the Japanese to invade Malaya. The success of OPERATION MATADOR depended upon fast decisions and timely movement by the British. The Japanese simply got inside their decision cycle and were already ashore before any orders to execute MATADOR were given. All elements of British strategy—command of the sea and air and an occupation of important ground—had failed to occur.

When the Japanese landed in southern Siam and northern Malaya on December 8th, they found themselves hundreds of miles north of Singapore. Allied troops, consisting mostly of Indians, Australians and British, stood between them and Singapore. The Japanese quickly dominated the obsolete Allied aircraft and gained air superiority. With the demise of Z Force, they controlled the sea, with the ability to land troops behind Allied lines. They also had the advantage of possessing nearly 200 tanks, while the Allies had none.

When the Japanese landed in southern Siam and northern Malaya on December 8th, they found themselves hundreds of miles north of Singapore. Allied troops, consisting mostly of Indians, Australians and British, stood between them and Singapore. The Japanese quickly dominated the obsolete Allied aircraft and gained air superiority. With the demise of Z Force, they controlled the sea, with the ability to land troops behind Allied lines. They also had the advantage of possessing nearly 200 tanks, while the Allies had none.

The Japanese initially encountered Indian troops. Fire and maneuver won the day; they simply bested the Indians in combat and outflanked resistance by leaving the roads and infiltrating behind Indian positions. Even without many trucks, the Japanese kept up a steady advance thanks to bicycles. Bicycles abounded in Malaya and Japanese troops took them for their own use. Traveling in groups of 60 to 70 men, they pedaled their way down the peninsula, which gave rise to the campaign’ nickname, the Bicycle Blitzkrieg. The Japanese also conducted just enough landings behind Allied lines to tie up opposing troops. By the end of December, the invaders were halfway to Singapore.

The Japanese retained the initiative in January 1942. The Allies inflicted some casualties through ambushes and fought delaying actions to enable comrades to escape capture, but the Japanese never faced a serious counterattack, let alone a counteroffensive. Additional Allied troops arrived, but not enough to stop the onslaught. The end of the month found the Allies blowing a 20-meter gap in the causeway bridge linking Singapore and Malaya. The battle for Malaya was over; the fight for Singapore proper was on.

Responding to pleas from Australia and New Zealand that Singapore be better defended, Churchill sent reinforcements. These included the 18th British Infantry Division and 44th Indian Brigade—the latter only partially trained—as well as nearly 50 Hurricane fighter planes. But the Japanese paused for only a few days before landing on Singapore on February 8th.

Churchill ordered that Singapore should be defended vigorously and that commanders should die with their troops. The Allies fought to hold on to the high ground at Bukit Timah, the location of their food and gasoline depots, but lost the position on the 11th. With the Japanese threatening Singapore city proper, the Allies pulled back their troops from the eastern section of the island on the 12th, a move that left Singapore’s water reservoirs in Japanese hands.

Low on food, water, and ammunition, the British command ruled out a counterattack. The Allies attempted to withdraw some personnel, but the Japanese sunk most evacuation boats.

Seeing further resistance as futile, on February 14 Churchill reversed himself and authorized the surrender of Singapore. Lieutenant General Arthur Percival, the British commander of the British and Commonwealth forces at Singapore, sought terms. The Japanese commander, Lt. Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita, told him that any surrender would be unconditional. Percival complied. Reports of the number of troops surrendered to the Japanese range from 60,000 to 100,000 men.

Ironically, Percival surrendered to a force that was much smaller than his own—Yamashita reported his strength as only 30,000 men. Yamashita’s troops were also quite low on ammunition, but Percival could not have known that. The Japanese had advanced over 500 miles in just over 70 days to capture not only their objective, but most of the Allied army as well.

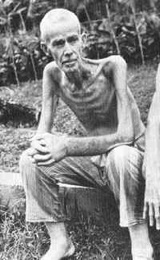

Surrender did not bring an end to the suffering, which simply entered a new phase. The Japanese executed, tortured, and killed thousands of prisoners. Other prisoners of war were worked to death. Civilians fared no better. Any amazement or awe of the Japanese victory over their English colonial masters was quickly forgotten under Japanese rule. Citizens starved as the Japanese shipped food elsewhere. The Japanese tortured or killed others suspected of aiding the Allies. Japan’s post-war estimate of civilian deaths is 5,000, but other sources place it as high as 50,000.

Surrender did not bring an end to the suffering, which simply entered a new phase. The Japanese executed, tortured, and killed thousands of prisoners. Other prisoners of war were worked to death. Civilians fared no better. Any amazement or awe of the Japanese victory over their English colonial masters was quickly forgotten under Japanese rule. Citizens starved as the Japanese shipped food elsewhere. The Japanese tortured or killed others suspected of aiding the Allies. Japan’s post-war estimate of civilian deaths is 5,000, but other sources place it as high as 50,000.

Some revisionist historians blame Churchill for the debacle at Singapore. Churchill did not want to lose Singapore, and he needed to demonstrate to the Australians and New Zealanders that he was trying to defend it; hence, the reinforcement of troops and aircraft in January. Did he make promises to the Australians and New Zealanders that he could not keep? Yes, but Japan shocked the entire world by attacking not only Britain but the United States as well. Could Churchill have ordered a larger fleet to Singapore? Yes, he could have. But the Battle of the Atlantic was raging—it would not reach a climax until 1943—and was a very "near-run thing." Even if Singapore could have been defended with a strong British fleet, would holding it have been worth losing the Battle of the Atlantic? Of course not.

Should Churchill have sacrificed the Mediterranean by sending aircraft and tanks to Singapore as he had promised? No, protecting the Middle Eastern oil fields from German occupation was much more important than Singapore. The same goes for aid to the Soviet Union. With German troops in sight of the Kremlin in December 1941, the Soviet Union needed all the help it could get from Britain in fighting their common enemy.

The blame for the fall of Singapore can be put on Churchill, but that is simply indicative of the fact that he was in charge. Were his decisions faulty or callous? No, rather they were taken as part of the overall war effort. However tragic the fall of Singapore was for its citizens and defenders, however betrayed they and the Pacific Dominions felt, Churchill made the correct decisions.

February 15, 2012, will mark the 70th anniversary of the fall of "impregnable" Singapore to Imperial Japanese forces. In recognition of that anniversary, Armchair General is publishing this article and an accompanying slide show of photographs taken at two Singapore museums that preserve the history of those momentous days in World War II. Click here to see Hans Johnson’s article and images, the Fall of Singapore museums.

About the author

Hans Johnson is a freelance writer who lives in Florida.

There wasn’t much that Churchill or anyone else at Whitehall could have done. At this stage of the war, the British Empire had too many holes in the dyke and not enough fingers. Their desert army consumed all of their own as well as US lend Lease armor-an asset that might have turned the tide in Malaya. The RAF was also stretched by having to operate in the Mediterranean Theatre and to defend the UK. It had only been in teh last 6 months that Germany had switched her priority from pursuing an air war over Britain’s skies. The Royal Navy had even bigger problems, fighting the War in the Atlantic, struggling to control the Med (they had been badly mauled in the Greek/Crete campaign/ and trying to keep the Indian Ocean open

By now they were exporting first line aircraft to bolster the Red Air Force, so that is why there was nothing left but Brewster Buffaloes and

second line troops for Singapore, as well as weak naval formations

Those planes that Churchill insisted got sent to the USSR proved of little value. Even Stalin himself remarked how the Hawker Hurricane was no better than their own LaGG flying coffins. Because they simply were poorly suited to the conditions, being high maintenance and unable to cope with the colder climate.

They could’ve and should’ve been given to Brook-Popham. No excuses, Malaya and Singapore fell because of Churchill’s interfering negligence.

Given the subsequent cold war it is questionable that modern aircraft and assistance in general was sent to the Soviets at this time.

I do think that Churchill deserves some blame for the Singapore debacle, not for decisions made in December 1941 to February 1942, but for one made in March 1941 – to divert resources (notably troops, tanks, and aircraft) from Libya to Greece. Said diversion was honorable and well-intended; Greece had bravely and successfully fended off the Italian invasion, and were about to face the fury of the Germans. But, Churchill’s decision to put forces into Greece prevented the arguably likely prospect of finishing off the defeated Italians in Tripoli.

Had Connor’s force not been depleted for the Greek enterprise, it may well have defeated the Italians in the same manner as Commonwealth forces would in Ethiopia. Thus, no Afrika Korps, no Desert Fox, no Western Desert see-saw campaign of two more years, no serious threat to British hegemony in the Middle East. Resources, especially tanks and first-line Spitfires & Hurricanes, could have been spared for Malaya.

The end result may have been the same. But a more effective defense of Malaya-Singapore may have been accomplished with the resources freed up by an earlier British victory on the North African littoral. Thus, one could argue that the seeds of surrender in Singapore were planted in the defeats of Thermopylae and Maleme, and in the missed opportunities in Tripoli.

My father’s cousin, David Gates, was with the 18th Infantry division. He arrived just in time to be surrendered to the Japanese. He survived the war in a Japanese concentration camp, somehow, but looked like a skeleton. He died only five years later in 1950.

The real question here is how fossilized was the British military to the point where an army of 80,000 gets outfought by an army of less than 35,000. Where were the plans? who thought that routine and procedures could avoid the blitzkrieg style attacks of the Japanese. Britain had already suffered this and barely escaped at Dunkirk. Why were the lessons of WW1, infiltration tactics, and those of the blitzkrieg not taken into account?

Because (although few admitted it) the troops in Malaya were to be charitable 3rd rate. The Indian Army troops that made up the majority were regulars in title but recent draftees in fact, the regulars sent to the Middle East of detached to form new battalions. The identical titled battalions of the 4th and 5th Indian Divisions were as good, usually better, than any enemy faced – those of the 9th and 11th Divisions in Malaya easily routed. Even worse were the brigades of the Indian State Forces, some of whose battalions mutinied and one of which shot their commanding officer. Even the Australians were less impressive than expected (ignore the endless propoganda from Aussieland that invariably blames others for defeats). Mind you they had the excuse that their general was an utter coward – the only senior officer to run away and not stay with his troops when Singapore fell.

In fact the unit your relative served with (the 18th Territorial) was the best around. It held its line to the end, finally surrendering when the Indian and Australian brigades to its east were defeated.

Of course the basic weakness was the behaviour of the Conservative Party in the ’30’s, whose leaders (including Churchill) were not concerned with the military.

I’m sorry but that is absolute nonsense.

I don’t know what you think you know, but I can assure you now; the Indian army soldiers in Malaya proved themselves tough opponents for the Japanese. The actual Japanese beachhead in Malaya was almost defeated buy Indian army defenders!

Despite everything; the campaign was not a push-over for the Japanese as Churchill and propaganda-fed popular British history has led people to believe. The British, Indian and Australian soldiers put up tough fights against long odds. The fact you’ve not mentioned the Argyll and Sutherland’s proves how little you really know.

Although it is true that Australian general Bennett shamefully abandoned his command. But you can’t fault the rest of the Aussies.

I can’t help suspecting there’s an element of nationalist stereotyping and racism in your misconceptions.

Rubbish – every historian of the Indian Army has acknowledged that the performance of units in Malaya and Burma was far inferior to that of the same sort of units in Libya and everywhere else. And the same is true of the Australians. And as for the A&S the only reason why they were considered to perform better was because they were on detached service training for jungle warfare and therefore missed the initial debacle in the north of Malaya. And I most certainly can fault the ‘rest of the Aussies’ – if you had bothered to read the histories you would know that it was through the Australian and Indian fronts that the Japanese crossed the waterway before Singapore, forcing the surrender of the island

Facts are somewhat more important that illusionary and invented references to racism.

Too well said @Been Benuane. One simply cannot discount the great efforts , fighting spirit and sacrifices of the Forces defending Singapore and Malaya. Take into account, for example, 2nd Lt. Adnan bin Saidi of the Malay Regiment in SG. During the battle of Pasir Panjang Ridge, he fought bravely and valiantly. When they were forced to retreat to Bukit Chandu(Opium Hill), he foiled the Japanese soldiers’ attempt to infiltrate their ranks as Punjabis due to his sharpness and eagle eye. The Malay Regiment was short of ammunition and supplies, but in their bravery, continued to resist the Japanese Army. 2nd Lt. Adnan fought bravely, bringing down many Japanese men. Even when captured and brutally tortured by the Japanese, he refused to surrender. They bayoneted him viciously and as if that was not enough, tied him in a cocoon and hung him on a tree, where they continued their bayoneting and stabbing of him. He and the Malay Regiment lived up to Lt. Adnan’s personal motto: Death before Dishonour. Despite being outnumbered 1.4:13 , the defenders of Pasir Panjang ridge fought to their graves, taking down more men with them. So, @David Hughes, do you think that that can be described as a mere ‘charitable force’? Is taking down much more than 10 men to their graves on average a ‘inferior’ force? The details of Lt.Adnan’s cruel death are written in blood. The forces defending SG were anything but ‘push-over’. However, the commanding officers were at fault for underestimating the enemy and their unwillingness to face the enemy in battle.

Considering the Japanese advancement through the causeway, it was the British Officials poor judgement and embarrassing blunders that caused the withdrawal of forces to SG and the partial destruction of bridges meant to impede the Japanese advance. However, labourers simply rushed in and rebuilt them quickly. The Japanese army made full use of stolen bicycles. Seen by the Japanese’ victory in Malaya and SG, it was the bicycle which was the greatest invention of the 20th Century.

Furthermore, The average British there were more then overconfident and complacent. The then governer of SG, said to his clerk in response to her query and I quote, “What did you say? A Japanese bomb dropped in Singapore? There will never be a Japanese who would set foot in Singapore.†Despite the Japanese forces right at their doorstep, balls and leisurely activities continued at Raffles Hotel in SG as if the war was not going on, save the enemy next door. They were clouded by their thought of the ‘greatness and superiority of white man’.

To conclude, the forces defending SG fought bravely and valiantly. However, the meagre and inadequate resources given to Percival to defend Singapore & Malaya and the numerous tactical blunders made by the British caused the fall of Singapore & Malaya.

The simple fact was that Churchill had clearly neglected the defense of Malaya and Singapore.

He sent hundreds of aircraft and aid to the Soviet Union, many months before the Japanese invaded Malaya. But it was home-made units like the Il-2 Sturmovik aircraft and T-34 tank which proved decisive factors in winning the war on the Eastern Front. None of the aircraft or tanks sent by the British were given any credit.

Churchill also clearly underestimated the Japanese. He and his War Cabinet did not believe the Japanese had bomber aircraft capable of flying at a very long-range. They did not believe they had superb fighters like the A6M Zero (despite reports from China after one was captured intact). He sent only one battleship and one battlecruiser (the Prince of Wales and Repulse) when the Japanese attacked with dozens. Last but not least, they never thought the Japanese would really invade until after they had landed in Malaya, after all Japan had never preceded hostile action through declaration of war. Some ‘War Cabinet’ Churchill had.

On second thoughts it would have been more appropriate to have headed the article ” were Churchill/MacArthur/Percival/Roosevelt responsible for the Fall of Singapore/Manila/Malaya/Philippines”. All western leaders seem to have been like Churchill (as Aubrey above states) in grossly underestimating the capabilities of the Japanese. The reasons were multiple, one of the least realised and powerful, being the influence of Christian missionaries in China. These were endlessly pressing for Western involvement after the Nanking Massacre, invariably accompanying their demand with claims that the Japanese were just disorganised, brutal and primitive (and non-Christian) barbarians that were easy prey!

Lt. Colonel Francis Hayley Bell was appointed as MI5’s Defence Security Officer in Singapore in 1936 and had expert knowledge of the Far East, having previously been Commissioner of Tientsin before his arrival in Singapore. In the 1930s Hayley Bell penetrated a Japanese spy ring and learned of the Japanese plans to invade, not by sea, south of Singapore, which was defended by the famous “big guns”, and from where everyone thought an attack would come, but Hayley Bell knew and reported back to London that the Japanese planned to invade from Siam and Northern Malaya, and that it was their intention to move their troops down the Malay peninsula to attack Singapore north of the island. Despite the British Government propoganda during the 1930s of the so called strength of “Fortress” Singapore, Hayley Bell knew just how vulnerable Singapore really was but his warnings to Churchill, the British Government and to the Governor of Singapore were ignored. Churchill and the British Government were made aware of and knew about the Japanese plans to invade from Siam and also the truth about Singapore’s vulnerability and ability to withstand an attack long before Britain was involved with the war in Europe, when something could have and should have been done.

In order to demonstrate just how vulnerable Singapore was to enemy attack, Hayley Bell directed a small force posing as saboteurs to stage a mock commando raid on the island’s vital installations. Commandos simulated an attack on the recently completed Naval Base which would have disabled both the graving dock and floating dock. They aso managed to “set fire” to the RAF’s fuel dump, “sink” a fleet of flying boats moored near RAF HQ, “destroy” the switchboard at the civil telephone exchange and “bomb” the main power station, all without being detected. The operation caused outrage at both Government House and Fort Canning, the military HQ in Singapore and following complaints to the War Office in London, Hayley Bell’s services were terminated at just the time when had his warnings to the British Government been heeded and, had he been allowed to continue his job as Singapore’s Defence Security Officer, his work may have determined subsequent events in Singapore very differently……

My father who went out to Singapore to join the Borneo Company in 1932, and was a friend of Lt Col Hayley Bell’s daughter, Elizabeth, and her busband who both lived in Singapore. My father was part of the Malayan Naval Voluntary Reserve force during the Thirties and joined the Royal Navy at the outbreak of war when he took part in the evacuation of retreating allied troops off the coast of Malaya, the blowing up of the Causeway joining Singapore to the mainland, destroying boats and junks in the area to delay the invasion of Singapore itself. He left Singapore just hours before surrender on a convoy of ships escorting a Fairmile launch taking Rear Admiral Spooner and Air Vice Pulford, amongst other senior service personnel, who were given permission to leave in order to continue the war against Japan from elsewhere. Both Spooner and Pulford sadly died of starvation on one of the islands near Sumatra after their launch was machine gunned and beached. Pulford is alleged to have said to Spooner, “Of course we will be blamed (for the loss of Singapore) but look at how little resouces we had…” . My father’s ship was one of the many torpedoed and sunk between Singapore and Sumatra, He was rescued from the water by HMS Tapas and taken to the island of Singkep to continue the preplanned escape route across Sumatra to the east coastal port of Emmahaven (Padang) where he boarded one of the later evacuation ships leaving for Java and Western Australia. After this ship was also sunk by the Japanese Navy, he swam ashore, where he lived for several weeks in a Sumatran village until he eventually gave himself up after the Japanese ultimatum to shoot whole villages, if local people were caught helping the Allies. He was imprisoned initially in Sumatra, then taken back to Changi in Singapore and later Formosa where he spent 3 years at Shirakawa, which was known as the Officers’ Camp and where the prisoners did backbreaking work farming and raising lifestock as “White Coolies”….When released by the US Navy, he was just 6 stone.

Ms Gradson: Thank you for that account, both the moving recital of your father’s exploits and suffering and of the incompetant response to Colonel Bell’s findings.

It certainly confirms the stories that the real villians in the peace were the senior officers of the Foreign and Colonial Service, men determined to maintain the appearence of normality, regardless of the facts placed before them. At a time when promotion meant ‘do not rock the boat’, it is not surprising that accurate fears of Japanese attack were discounted and those who suggested them disciplined.

It is often forgotten that the ‘senior officer in Malaya’ was not Percival the General but the Governor, a typical and mediocre appointee who flatly ruled against any defence actions that might offend the local Sultans, the business community or even the Japanese envoys.

The failure of intelligence caused this disaster. To procede as if you are living in the 1850s and plan a war according to the American Civil War era in the 1940s, is inexcusable. Fossilized minds are not going to learn anything very soon.

It must be pointed out that the Japanese were very intelligent in their use of bicycles as a cavalry in the jungle. Solid tyres, not pneumatic ones, were the key here. Must have been a pain riding them, but they were effective.

The real problem here was prejudice and mental fossilization. The inability to understand your enemies leads to disaster. Barbara Tuchman’s ‘The March of Folly’ records this. Singapore should have been on her list.

The British failure in Singapore can be traced to Churchill’s failure to read , understand and examine the intelligence reports that were available to him and he didn’t listen to people in the War Cabinet and military who had. In 1936/37 Malaya Command reports were made to the British military that a land based defense of Singapore was essential, the landing places in Northern Malaya and southern Thailand were correctly guessed by both the military and British intelligence. Air Marshall Brooke Popham was made head of British Far East Command on the 18/11/40. The appointment of an RAF man to head the defense of Britain’s biggest naval base outside the UK speaks for itself. Churchill made the correct decision in 1940 that air power would be the deciding factor in the defense of Malaya and Singapore. He just never sent the planes.

After a review of the available information Brooke Popham. Confirmed earlier estimates that the air defense of Malaya and Singapore would require mixed force of fighters and maritime attack / strike aircraft number 300 to 500 aircraft to be successful. Based on this estimate 250 Hurricanes were made to tropical pattern to meet this requirement. In August 1941 with crated planes being loaded on to ships for Singapore, Churchill personally intervened to keep a promise to Stalin, these planes were sent to Russia. Half of them were sunk on route. These planes had to have the tropical gear stripped off to be used in the Russian climate. The thing is that Brooke Popham was told these planes were still coming.

50 Hurricanes were sent to Singapore in late January 1942. Further the Japanese got the British strategic and diplomatic plans for the Far east in November 1940 when Brooke Pophams personal orders directly from Churchill/GHQ along with code books and other crucial documents were captured on the SS Automedon by the German surface raider Atlantis. After this information was passed on to the Japanese by the Germans, they were better informed than British Far east command. Unbelievably the British didn’t revise their codes, policy or war plans, they didn’t supply Brooke Popham a new copy of his orders. He had to learn it bit by bit deducing it from telex and letters piecemeal. Brooke Popham along with Percival are often blamed for the fall of Singapore. Close examination of the records shows these men to to be intelligent, brave men whose requests for material and commence pro active military action were ignored until it was too late. In 1948 after the war Brooke Popham wrote a letter asking what happened to his1940 orders and he was lied to and told the Automendon was sunk by Submarine. ie the papers were destroyed not captured.

The RAAF and RAF were placed in the northern airfields to strike invasion force before they could disembark troops. These air field needed to be defended. Brooke Popham and Percival’s Operation Matador was needed to be put into operation but political pressure directly from Churchhill over breaching Thailand’s neutrality

stopped this plan being implemented until it was too late.

Being Bo Polar and a practicing alcoholic Churchill’s character was prone to ill advised , ill informed, snap decisions. Good politician and public moral booster may be but when he interfered at the tactical and command level it was a disaster.

Disaster after disaster for the British can be routed home to this. The Norway invasion, the support of Finland, Greece, Crete, mismanagement of the desert war, the Diepe Raid, and Singapore. After the Italian campaign bogged down and Casablanca Conference was held Churchill’s direct interference in military decisions was not possible because of the combined US British command structure. Its after Churchill’s direct interference stopped that the Allies start winning.

Sure, the British Officials back in jolly old England made lots of mistakes and the Japanese sent their 3 most toughest trained divisions to land in Siam, but the British in SG made their fair share of mistakes and tactical blunders. It could be well said that Percival was fighting with his hand tied behind his back. However, his high command DID make their fair share of mistakes such as their unwillingness to face the Japanese in battle, the underestimation of the Japanese forces and the intelligence collected by the Japanese, their constant retreats and withdrawals and the partial destruction of bridges( somewhat ineffective due to labourers who rushed in to repair the bridges).

Winston Churchill, Bi Polar Alcoholic.

He played a central role in planning the disastrous military campaign at Gallipoli during WWI, leading to a quarter-million Allied casualties. Worse, his decisions during the Second World War led to the fire-bombing of German cities by the Royal Air Force (the bombing of Dresden is one of the rare examples in which the American Army Air Corps joined the RAF in the purposeful incineration of civilians).

Mental Health

Churchill is alleged to have slept only four hours, drunk an entire bottle of port before retiring and three scotch and sodas before lunch alone. Upon the subject of his alcoholism, Churchill remarked with characteristic dryness “I have taken more out of alcohol than alcohol has taken out of me.

My father was involved in the New Guinea campaign, my brother in laws father was a POW in Changi, my wife’s father was in the middle east.

The words these people and other veterans, I have known all speak badly of Churchill.

Churchill’s aim was to protect England at any cost!

I worked with a teacher in China for nearly one year, who suffered from bi polar. This person was self medicating mainly with alcohol and some drugs. Never taking the prescribed medicine.

I could write a book on what was happening with this person. Unbelievable, massive highs and lows, no sleep, manipulating clever liar, rage, kindness, student predator and so on.

From my observations these people with bi polar disorder who are not on any prescribed medication only care about themselves and are basically out of control.

Hans Johnson, you make a lot of excuses for Churchill.

The fact remains; in 1937 the British command in the far east presented Operation Matador, which was a strong defensive plan for Malaya. While Britain undoubtedly already had a lot on its plate with the war in Europe against Germany and Italy; they certainly had the resources to enact operation Matador.

They had the surplus obsolescent aircraft that could’ve matched the Japanese aircraft in the lower altitude battles, but Churchill instead insisted they got given to the USSR to be wasted piecemeal.

They could’ve spared more naval units for force Z including another Illustrious class carrier to replace HMS Indomitable. But Churchill was more focussed on a vague threat of two German Battlecruisers (and a couple of pocket battleships), which would need to sortie through areas of RAF air superiority and would need to combat the Royal Navy’s numerical superiority.

They could’ve deployed an entire army corps to the Malayan peninsular in 1939 or early 1940 and had them acclimatised, properly based, supplied and even more prepared as the Argyll and Sutherland’s proved. British India could’ve supplied ample manpower against a Japanese threat.

Britain would’ve struggled to supply enough quality armour, but Britain could’ve supplied enough anti-tank guns along with anti-aircraft guns.

But Britain didn’t. And that’s solely because of Winston Churchill. Nothing to do with any shortage of resources. Because Churchill could never fathom how the Japanese may actually be the strong threat they subsequently proved. In a similar vein to how he never understood that Italy was not in fact a soft underbelly of Europe. Or that Alpine troops would easily outflank and outfight British Tommies with no mountain training in a place like Norway. Or that the Dardanelles has more than mere gentle slopes in its topography. I honestly doubt if the man ever had to walk up many hills on his life.

No excuses, please just concede that it was one of the many blunders of a politician whose main talents seem to have been making verbose speeches, writing self-indlging personal memoirs, gambling and drinking.

I think that 100 Hurricanes and mixed force of 150 Stuart Valentine and Matilda tanks would have made Singapore totally invulnerable. That’s Churchill’s fault.

The British High Command In SG felt that Tanks in the jungles were not a feasible idea. The British actually had parts and pieces of some fighters which could have been easily assembled and deployed in action. These could have been used to take down the observation balloon set up by the Japanese to direct their mortar fire on SG.

Unpopular opinion: Churchill was responsible for most of World War 2 and its casualties.

Given the subsequent cold war it is questionable that modern aircraft and assistance in general was sent to the Soviets at this time.