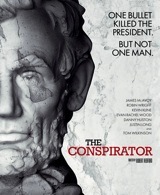

The Conspirator – Movie Interview

Armchair General‘s Jim Zabek had the opportunity to interview Fred Borch, history advisor for the recently released movie The Conspirators, which depicts the trial of the conspirators in the plot to kill President Abraham Lincoln, in particular the accused conspirator Mary Surratt. A recent poll on our partner site, HistoryNet.com, found that 41% of those who took the poll felt she had a minor involvement in the plot and 30% believed she was deeply involved. Just 14% said she was not involved in the conspiracy at all.

Jim Zabek (JZ): Please tell us a bit about yourself so that we can introduce you to our audience.

Jim Zabek (JZ): Please tell us a bit about yourself so that we can introduce you to our audience.

Fred Borch (FB): I’m a retired Army officer and lawyer (served 25 years active duty in the Judge Advocate General’s Corps) and now work as the Regimental Historian and Archivist for the JAG Corps. As far as I know, I am the only full-time military legal historian in the United States. In addition to three law degrees, I received professional education and training as a historian at the University of Virginia.

{default}JZ: Why is it important that Army lawyers have some knowledge of history?

FB: You can’t understand why we practice military law the way we do today—or the role played by judge advocates in the Army today—if you don’t understand what we have done in the past and why things have changed. Even more importantly, you can’t make good decisions about the future without knowing what has happened in the past. Actually, almost all Army lawyers understand how important a good understanding of history is to our profession—so that makes my job much easier as the historian for the JAG Corps.

JZ: How did you come to be involved in the movie?

FB: I gave a speech on the Lincoln assassination trial at a Civil War history conference a few years ago, and met a researcher who was working on the script for the movie. She asked me some questions about the trial of Mary Surratt and the other conspirators and she later recommended to the producers of The Conspirator that I be hired as a history advisor. So that’s how it all started. After that, I reviewed the movie’s script on more than a few occasions—ensuring historical accuracy—and spent a few days on the set in Savannah, Georgia, during filming in October 2009. At this time, I met briefly with the director, Robert Redford, but spent more time with James McAvoy (who plays Mary’s principal lawyer), Tom Wilkinson (who plays Senator Reverdy Johnson, also one of Mary’s lawyers). Later, I spent many hours on the telephone with actor Danny Huston, discussing the life of the man he portrays in the movie, Brigadier General Joseph Holt, the Judge Advocate General. Holt was the lead prosecutor at the military commission.

JZ: Was your work part of your regimental historian duties, or did you do this in your personal capacity?

FB: One hundred percent in my personal capacity. There are strict ethics rules that govern what I can or cannot do as a government employee — and these rules require that any sort of consulting on a commercially produced movie be done on my own time and away from the office. I actually had to get a formal ethics opinion before I could agree to work on The Conspirator.

JZ: How did you and Dr. James McPherson work together? Were there parts you did separately and others in which you worked together?

FB: We worked well together, if for no other reason than our talents as historians were complementary. By that I mean that as my expertise is military legal history, I naturally focused on the trial itself and legal questions surrounding the prosecution of the eight conspirators at a military commission. Jim McPherson, who is one of the foremost experts on the Civil War—his Battle Cry of Freedom is the best single volume history of the Civil War—advised on broader historical questions.

JZ: How are the military commissions today similar to the one that tried Mary Surratt? What are the major differences?

JZ: How are the military commissions today similar to the one that tried Mary Surratt? What are the major differences?

FB: This is really "apples" and "oranges." The most fundamental difference is that the military commissions operating today were created by Congress in 2006, using its powers under Article I of the U.S. Constitution. The military commission that tried Mary Surratt had been brought into existence by President Andrew Johnson, utilizing his powers as Commander-in-Chief under Article II of the Constitution. That may sound like a legalistic answer, but it really isn’t because the Constitution is the starting point for everything in our country, so how tribunal or court is brought into existence is important. Other major differences are that there was no presumption of innocence at the military commission that heard evidence against Mary Surratt, there was no judge to rule on evidentiary issues or to conduct of the prosecution or defense, and there was no appeal from the commission’s verdict in 1865. The military commissions created by Congress in 2006 are completely different and are all about ensuring a full and fair trial for the accuseds who appear before them.

JZ: Was Mary Surratt guilty? Was there any exculpatory evidence you know of that wasn’t presented at trial? Are there any particularly good arguments that she was not guilty?

FB: There is no doubt that Mary was part of a conspiracy to harm President Lincoln. She certainly conspired with John Wilkes Booth and others to kidnap the president. At trial, the testimony of John Lloyd was the government’s proof that she knew that the kidnapping plan had been transformed into a murder plot. Lloyd stated under oath that Mary had driven out to see him on April 14, 1865, and instructed him to have some rifles ready for pick-up by "other parties." When Booth and his fellow conspirator, David Herold, showed up later that day—after Booth had shot Lincoln—Lloyd in fact gave the rifles to them. But did Mary actually know that Booth was going to assassinate the president that night in Ford’s Theater? Lloyd’s testimony was enough evidence that she did. There is, however, another basis to find her guilty and that is the law that governs liability for a conspiracy. If an event is foreseeable, then everyone in the conspiracy is guilty, even if they didn’t think that event would happen. For example, in a conspiracy to sell marijuana, if one of the conspirators decides to sell heroin instead (or in addition to marijuana), then all the conspirators are criminally liable for selling heroin. That’s because in a conspiracy to sell marijuana, it is foreseeable that other drugs might be sold. In a conspiracy to kidnap, a homicide is foreseeable because kidnapping is a violent crime and it is foreseeable that the victim might be killed. After all, the victim might resist the kidnapping. So suppose that Booth and the conspirators had tried to kidnap Lincoln, and he had resisted and been killed? They’d be guilty of murder—because the killing was foreseeable in a kidnapping conspiracy. That’s why the law says Mary is guilty in this conspiracy, too. So I don’t think there are any good legal reasons to say that Mary was not guilty—there was sufficient evidence for the seven generals and two colonels who heard her case to convict her.

JZ: How do you interpret the fact that Mary Surratt was executed shortly after the assassination, but when her son was captured over a year later charges against him were dropped?

FB: Four factors. First, when Mary Surratt was tried, there was every reason to believe that she had been part of a diabolical conspiracy that included the top leaders of the Confederacy, and her quick trial and hanging reflected a desire on the part of the government to send a message that this sort of attack on the Union’s leadership would not be tolerated and would be punished severely. So Mary’s trial was all about getting quick results. Second, when her son was prosecuted, his trial was in a civilian court where more than a few jurors had Confederate sympathies and where a unanimous verdict was required. Pretty tough to get a conviction when a unanimous verdict is required and there is a good chance at jury nullification—and John Surratt’s trial resulted in a mistrial because there was a hung jury. Third, John Surratt was very smart: at his civilian trial, he admitted to being part of the kidnapping plan but denied knowing that Booth had transformed the conspiracy into a murder plot. Since Surratt had been in Canada at the time Lincoln was killed, this was enough "reasonable doubt" to preclude his conviction. Fourth, the country wanted to move on—to get the assassination behind it—and this had to have been a factor in John Surratt’s ultimate freedom, too.

JZ: Do you believe any anti-Catholic bias affected the conviction of Mary Surratt?

FB: No doubt. In Protestant America in the 1860s, Catholicism was seen as subversive and anti-Republican. You can be sure that some of the commissioners who voted to hang her were prejudiced against Mary because of her religion and suspicious of her because she was such a devout Catholic. Remember that in 1960, there were more than a few Americans who proclaimed that they could not vote for John F. Kennedy because he was a Catholic. In 1865, this feeling was even stronger.

FB: No doubt. In Protestant America in the 1860s, Catholicism was seen as subversive and anti-Republican. You can be sure that some of the commissioners who voted to hang her were prejudiced against Mary because of her religion and suspicious of her because she was such a devout Catholic. Remember that in 1960, there were more than a few Americans who proclaimed that they could not vote for John F. Kennedy because he was a Catholic. In 1865, this feeling was even stronger.

JZ: Mary Surratt was the first woman ever executed by the United States government. What message do you think this sent?

FB: President Johnson and Secretary of War Stanton were trying to show that an attack on the government’s leadership would be dealt with swiftly and severely and that your gender wouldn’t save you from the hangman’s noose. But the hanging was a political disaster—it generated a lot of sympathy for Mary and this no doubt influenced the jury that heard John Surratt’s case. Some must have thought that the Surratt family had suffered enough.

JZ: Finally, how accurately would you say the movie portrays the historical events surrounding the trial of Mary Surratt?

FB: Obviously, we can’t know what Mary Surratt and her lawyer, Fred Aiken, actually said to each other. Some of the other dialogue is conjecture, too. But Jim Solomon, a brilliant writer and the principal author of the screenplay, was meticulous in adhering to the historical record, and since there is a complete transcript of the military commission proceedings, Jim was able to be very faithful to reality when it came to the trial itself. In my opinion, the movie definitely captures the spirit of the times—the Zeitgeist as the Germans call it.

JZ: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

FB: Go see the movie. Great director, great cast, great story. You won’t be disappointed.