Tactics 101 044 – The Staging Plan

For the Glory – PC Game Review (corrected link)

AIR ASSAULT

THE STAGING PLAN/REVIEW

“It is worth recalling that the Mongols, although their Army was entirely composed of mobile troops, found neither the Himalayas nor the far stretching Carpathians a barrier to progress, for mobile troops there is usually a way around.”

—Sir Basil Liddell Hart

LAST MONTH

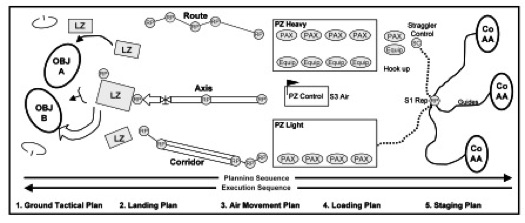

In our previous article, we focused on the fourth plan of an air assault operation – the Loading Plan. In dissecting this plan we touched on several areas. These included the selection of a Pickup Zone (PZ), the many responsibilities of the Pickup Zone Commander (PZCO), movement to the PZ, internal and external loading, the bump plan, and communications. We finally wrapped it all up with a diagram and displayed an example of a PZ. After reading the article, it should be pretty clear this is a very important plan. The bottom line is you must get the right people and the right equipment on the right bird at the right time. Clearly, a significant challenge!

THIS MONTH

We will conclude our mini-series this month on air assault. We will break out this article into three parts. First, we will look at the final plan – the Staging Plan. Second, we will provide you some detail on what should be included in the Air Mission Brief. This is in essence, the blueprint driving an air assault operation. Finally, we will wrap up the article with some overall keys to success in conducting an air assault. We will address each of the five plans and highlight the critical concepts we touched on in previous articles. Let’s begin.

THE STAGING PLAN

The staging plan is the last plan you will make and the first one you will execute in an air assault. When you get to this one you’re almost done! The staging plan is based on the loading plan and assigns the arrival time of ground units (troops, equipment, and supplies) at the PZ in the proper order for movement.

In simple terms, the Staging Plan is the tactical road march to the line of departure. In some cases, this can be a relatively short maneuver with minimal concerns (if there is such a thing). At the other end of the scale, this can be a significant maneuver with many moving pieces (and many headaches). The keys to a successful staging plan are details, preparation, leadership, and flexibility. We will address each.

In regards to details, there are several areas that must be planned. First, you must develop a viable maneuver table for all units involved in the air assault. Again, this is no different than planning a roadmarch. Second, you must develop graphic control measures that are in concert with your maneuver table. Finally, as in all details, they must be disseminated to all and understood by all.

One way to assist in understanding is in your preparation. Key events in preparation are rehearsals and reconnaissance. As discussed earlier, you must determine how much available time you have for rehearsals and conduct the most complete type of rehearsal you can. This may be a rock-drill, brief-back, walk-through, leader rehearsal, or a full-rehearsal. In terms of reconnaissance, walk or ride the ground from your current position to the PZ. The more familiar the better!

As in all the previous plans, leadership is vital. You must determine where the hic-cups can be and position yourself there. Make sure you have accountability of your people and equipment. Wayward groups of Soldiers enroute to the PZ is not a good way to get things started.

Finally, you must be flexible in mind, physically and mentally during the staging plan. As we all know, things will not go as planned during staging. For example, the birds can be late getting to the PZ, the maneuver table can get thrown off for a myriad of reasons, and oh by the way, your enemy can have a little influence on actions on the ground. Whatever the case, have some contingencies prepared and make the best out of whatever comes you way.

That is basically the Staging Plan. We tied in much of it last month in our discussion of the Loading Plan. Nothing can disrupt an air assault quicker than a poorly planned, prepared, or executed Staging Plan. As we have stressed from the start, each plan of an air assault is linked with other. Consequently, issues in the Staging Plan have consequences each the other four plans.

AIR MISSION BRIEFING

One of the key points we have highlighted throughout our discussion is the amount of detailed planning that must be conducted in planning an air assault. The piece that goes hand in hand with this is that it must be then articulated to the executors in a way that is understood by all. That is no small feat!

In the air assault world, we have one tool that can assist us in achieving both. This is the Air Mission Briefing (AMB). Let’s talk about the briefing itself and provide an annotated shell of the briefing. This shell will show you some of the details that should be considered in the overall air assault plan. Let’s start by discussing the briefing in general.

The AMB is the last coordination meeting of the key leaders involved in the air assault. Thus, you should have the following at the briefing: intelligence officer, operations officer, fire support officer, aviation liaison officer, air defense liaison officer, the operations officer from the lift aviation unit supporting the air assault, operations officers from the air recon and attack helicopter units supporting the air assault (if involved), communications officer, logistical officer, the Pick-up Zone Commander, the commander of the ground tactical plan, and of course the Air Mission Commander. Clearly, you better have quite a few chairs at the brief to seat everyone. However, as you can see each has a distinct role in the air assault.

The purpose of the AMB is two-fold. First, to lay out the details of the operation as the unit currently understands them. Second, iron out any of the loose ends that may still exist. The AMB literally goes from soup to nuts of the air assault. It includes each of the five plans and reviews the air movement table (which we discussed earlier in the series).

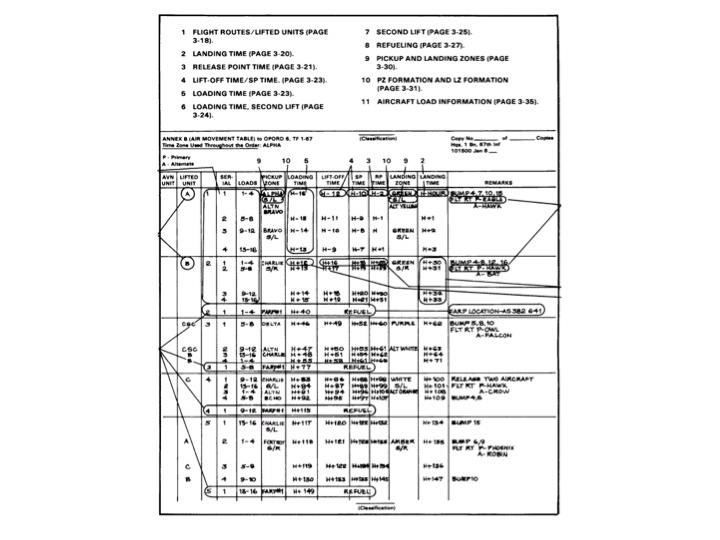

THE AIR MOVEMENT TABLE (A CRITICAL TOOL)

THE AIR MOVEMENT TABLE (A CRITICAL TOOL)

It is imperative the AMB takes place as soon as possible to allow for lower unit planning and preparation. In the perfect world (let us know if one exists out there), we want to use the old one-third, two-third rule (some units strive for a one-fourth, three-fourth split). To translate, you want to take one-third of the available planning time for your use and give your subordinates two-thirds of time. For example, if the first birds are to arrive at the PZ in twelve hours; you want to conduct the AMB in four hours and give your subordinates the other. Keys here are to issue warning orders throughout (to enable your subordinates to conduct some advance planning) and to ensure the AMB does not drag on; thus taking up your subordinate’s time.

Now that we have provided an overview of the AMB, let’s look at what should be covered. For those familiar with an Operations Order (OPORD); you will see they are very similar. For those uninitiated, we will dedicate a future article on the OPORD. In our discussion, we will highlight the key topics that should be addressed and provide some additional commentary on their importance

1. Situation. This paragraph should present extensive analysis and descriptions of the friendly and enemy based on the information available.

a. Enemy forces. Air assault orders require added emphasis on troop concentrations and Air Defense Artillery locations and assets. The enemy situation starts broad and general and becomes narrow and focused as you progress toward the end. The enemy situation includes the following:

- – Disposition: A general statement of where the enemy is and what is he doing.

- – Composition: A statement of how the enemy is put together in terms of men, weapons, and equipment both organic units and attached.

- – Strength: A statement of how effective we assess the enemy to be—of the XXX troops they normally have, YYY will be present and able to fight…

- – Capabilities: Outline the enemy’s capabilities in terms of maneuver, firepower, protection, counter-air, mobility, chem…. Again, in an AASLT operation we are particularly interested in air defense and early warning.

- – Course of Action: Here we propose what we think they will most likely do; other things they might do; and the most dangerous thing they could do.

b. Friendly forces. As with the paragraph above; we begin high and work down.

This is by design — get the big picture first and see how you fit in it.

- – Higher unit’s mission and intent: We need to know what our parent unit is doing and how our mission fits within their scheme.

- – Mission of the units to our right and left: What are the units on either side of us doing?

- – Mission of the nits to our front and rear: What are the units to our front and to the rear doing?

- – Reserve: Describe the size and power of the reserve and its planned employment.

- – Attachments and detachments: Show who has come into your unit and who is leaving your unit. You should annotate arrival and departure times. Critical in this discussion is to show your task organization and ensure everyone knows who belongs to whom and at what time.

c. Weather. Although always important, the weather is critical to an air assault

mission. Normal orders discuss visibility (our ability to see and be seen),

mobility (our ability to move) and survivability (weather impacts on

effectiveness). Air assault orders require extensive added information:

- – Ceiling and visibility at altitude

- – Wind, temperature, and pressure

- – Sunrise and sunset,

- – Moonrise and moonset, percent of moon illumination, end evening nautical twilight, and beginning morning nautical twilight

- – PZ and LZ altitudes

- – Weather outlook / forecast

2. Mission. Clear, concise statement of the task that is to be accomplished and the purpose for it usually stated in the form of the 5 W’s: who, what, and when, where and why.

3. Execution. We begin with a broad statement (Concept of Operation) of the overall mission to begin with the expanded purpose which links the ‘why’ of our mission to the ‘why’ of our commander’s mission. Next is the statement of how the unit as a whole will accomplish the mission which identifies key subordinate units and their key tasks while stating the decisive point for our mission. Last is the description of the desired end state—the commanders vision of where we should end up in relation to the terrain, the enemy, and to friendly units

a. Ground tactical plan. The heart of the operation…use the above format to specifically describe this portion of the operation. Add tasks (and purposes) to maneuver units, tasks (purposes) to combat support units, and tasks (purposes) to combat service support units.

b. Fire support plan. Outline fire support throughout the mission with emphasis on ingress, landing, and seizing and defending the objectives. Include the plan for suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD).

c. Air defense artillery plans. Any special air assault support is added to the normal description of air defense on the objective.

d. Engineer support plan. Discuss engineer tasks related to creating mobility (to include LZ prep), counter-mobility (cutting off threat reinforcements and counterattacks) and survivability (preparing fighting positions during consolidation).

e. Tactical air support. Describe the use of TACAIR in support of the insertion and then operations on the ground.

f. Aviation unit tasks. In this paragraph, we discuss the mission of the lift aircraft (Blackhawks) that will insert out troops. We also discuss the mission of the attack aircraft (Apaches) that support the insertion, then actions on the ground. We also cover aerial scouts (Kiowa’s) enroute, landing, and during ground operations.

g. Staging plan (both primary and alternate PZs). Provide a broad description of the staging plan using the same method as used in the concept of the operation paragraph. Add staging plan details as below.

- – Pickup zone location.

- – Pickup zone time.

- – Pickup zone security.

- – Flight route to PZ.

- – Pickup zone marking and control.

- – Landing formation and direction.

- – Attack and air reconnaissance helicopter linkup with lift elements.

- – Troop and equipment load.

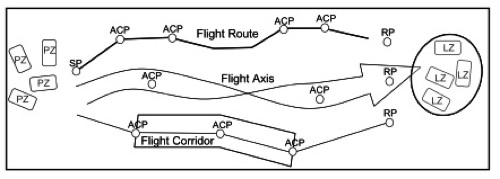

h. Air movement plan. Provide a broad description of the air movement plan using the same method as used in the concept of the operation paragraph. Add air movement plan details as below.

- – Primary and alternate flight routes

- – Penetration points.

- – Flight formations and airspeeds.

- – Deception measures.

- – Air reconnaissance and attack helicopter missions.

- – Abort criteria.

- – Air movement table.

i. Landing plan for primary and alternate LZs. Provide a broad description of the landing plan using the same method as used in the concept of the operation paragraph. Add landing plan details as below.

- – Landing zone location.

- – Landing zone time.

- – Landing formation and direction.

- – Landing zone marking and control.

- – Air reconnaissance and attack helicopter missions.

- – Abort criteria.

j. Laager plan (both primary and alternate laager sites).

- – Laager location.

- – Laager type (air or ground, shut down or running).

- – Laager time.

- – Laager security plan.

- – Call forward procedure.

k. Extraction plan (both primary and alternate PZs).

- – Pickup location.

- – Pickup time.

- – Air reconnaissance and attack helicopter missions.

- – Supporting plans.

l. Return air movement plan.

- – Primary and alternate flight routes

- – Penetration points.

- – Flight formations and airspeed.

- – Air reconnaissance and attack helicopter missions.

- – Landing zone locations.

- – Landing zone landing formation and direction.

- – Landing zone marking and control.

m. Coordinating instructions.

- – Mission abort: what conditions will cause us to cancel the mission.

- – Downed aircraft procedures: how do we protect and recover Soldiers and machines.

- – Vertical helicopter instrument flight recovery procedures.

- – Weather decision by one-hour increments and weather abort time.

- – LZ / PZ / MEDEVAC / Ammo DZ markings.

- – Unit link-up procedures.

- – Passenger briefing.

- – Commander’s critical information requirements (CCIR): critical information the commander needs to make key decisions—Priority Information Requirements (PIR) is enemy information, Friendly Forces Information Requirements (FFIR) is information about your unit and the units around you, and Essential Elements of Friendly Information (EEFI) is information that you must deny to the enemy that, if compromised, changes the mission. (Remember we spent an earlier article discussing this critical concept)

4. Service Support. Describe the concept of support throughout the mission. This includes Class I (food), Class III (fuel), Class IV (barrier material and mines), Class V (ammo), Class VIII (medical supplies) and Class IX (parts—mainly for TOW Hummers). Critical topics for air assault missions are the aerial MEDEVAC and aerial re-supply of ammunition.

a. FARP locations (primary and alternate). Where will the helicopters refuel?

b. Ammunition and fuel requirements. What is our basic load of ammunition and when, where, and how will we re-supply it.

c. Backup aircraft. Where do we get replacement aircraft from and where will they be physically located.

d. Aircraft special equipment requirements. Do we need special equipment such as cargo hooks (Slingload) and command consoles with headsets.

e. Health service support. MEDEVAC, casualty collection points, and battalion aid station location

5. Command Signal. Describe where key leaders will be and how they can be located and communicated with.

a. Signal.

- – Radio nets, frequencies, and call signs.

- – Communications-electronics operation instructions in effect and time of change.

- – Challenge and password: critical when operating behind enemy lines.

- – Authentication table in effect.

- – Visual signals: key to small unit communications on the objective.

- – MEDEVAC signals.

- – Navigational aids (frequencies, locations, and operational times).

- – Identification friend or foe (radar) codes.

- – Code words for PZ secure, hot, and clean; abort missions; go to alternate PZ and LZ; fire preparation; request extraction; and use alternate route.

b. Command.

- – Location of air assault task force commander, XO or second in command on the objective, and higher commander.

- – Location of the main command post, tactical command post, and rear command post.

- – Chain of command: succession of who takes over if the commander is lost or cannot communicate.

- – Point where air reconnaissance and attack helicopters come under OPCON as aerial maneuver elements.

6. Time Hack. All watches are synchronized.

THE AIR MOVEMENT TABLE (A CRITICAL TOOL)

Hopefully, we did not overwhelm you with the amount of detail that must be planned and understood in an air assault. However, the above should be an excellent reflection on the various aspects of an air assault that must be coordinated and how the five plans literally become one.

With our above discussion on the Staging Plan and the Air Mission Briefing complete, our mini-series on Air Assault Operations is also complete. We thought since we are nearing the Holiday Season, we would provide a gift to our dedicated readers. So here are some overall keys to success in conducting an air assault and some nuggets you should remember in each of the five plans. Unfortunately, if you do not like the gift it is not returnable.

AIR ASSAULT KEYS TO SUCCESS

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

1. DETAILED PLANNING: Distributed operations require exhaustive planning to include a comprehensive consideration of and planning for unexpected, but possible contingencies.

2. COMMUNICATIONS: An Air Assault Task Force (AATF) is initially dispersed. It must assemble and advance to its objective and often will not physically come together until final consolidation and extraction. Maintaining communications is the only way to fight and win with this distributed force.

3. EXTENSIVE USE OF INDIRECT FIRES: The AATF has very little support once it deploys deep into enemy held territory. What it does have is indirect fire from organic artillery and mortars, organic air support from Apache gunships and Kiowa Warriors, and Tactical Air (TACAIR). All must be planned for and used judiciously.

4. AGGRESSIVE EXECUTION: Air assault operations are unforgiving. To dither is to give the enemy an opportunity.

5. LEADERSHIP: As in all military operations, leaders are the key to success. From the brigade commander down to the squad leader; all must know their job, lead their men, and make decisions that compliment mission success. Issue clear orders and conduct comprehensive brief-backs and rehearsals.

Considerations for Each Plan

Ground Tactical Plan.

1. This plan must come first and it must drive all other plans. The tendency to allow air movement or landing at the PZ drive ground execution must be avoided. Make your ground plan first and adjust it to the landing and air plans if required. However, always remember the ground objective is the reason for the mission.

2. Don’t forget reconnaissance. An AATF cannot afford to be surprised.

3. Use all fire support available to you—fires kept the troops at LZ X-Ray alive.

The Landing Plan.

1. LZ selection is critical. Decide early on whether to land on, near to, or away from the objective based on enemy disposition and the mission.

2. Build deception into the landing plan such as false insertions and false prep fires. Any hesitation and misdirection of the enemy benefits your force when it is most vulnerable.

3. Survey your LZ’s. It is nothing less than disaster than to find the LZ will not accommodate the lift.

Air Movement Plan.

1. Plan for suppression of enemy air defense (SEAD). SEAD has to be deliberate and well thought out. It’s not the air mission commander’s job; it’s the ground commander’s job. Allocate scouts, air, and artillery to it. Helicopters that get shot down don’t land at the LZ, don’t deliver combat power to the objective and generate combat search and recovery (CSAR)—see Blackhawk Down.

2. Plan for alternate routes. There’s more than one way to skin a cat and contingencies must be considered when dealing with aircraft. Remember to be clear about abort criteria, administrative and enemy driven.

3. Army airspace command and control (A2C2) must be well coordinated, planned and executed. The AATF will not be the only thing in the air. Planning has to account for TACAIR, UAV’s, and artillery.

Loading Plan.

1. This is the first point where helicopters and men converge so PZ posture and control is essential. Lack of discipline on the PZ can abort a landing or a take off and thus the mission.

2. This is where the bump plan can save you. If an aircraft falls out, the bump plan allows you to maintain momentum.

3. Make sure your chalks are self sufficient and fit the buildup of combat power envisioned for the objective. They must be combat capable with key leaders cross leveled across the lift and prime movers are with their equipment (Artillery with their truck etc…).

Staging Plan.

1. Timing is critical—a blown staging plan execution leads to a blown operation. Everyone needs to be in place, on time, and ready to move to the next area while en-route to the PZ. Grab and establish positive control of attachments early.

2. Movement must be well orchestrated. Units need to know where their staging areas are and how long it takes to get to and from them. Quartering parties are key to getting units in place. Accountability of personnel and equipment is vital throughout the process and is aggravated sine this often occurs at times of limited visibility.

3. Since the staging plan is all about the interplay between timing and movement it requires detailed rehearsal on or about the same level as the rehearsal of actions on the objective. Rock drills, brief-backs, walk-throughs, leader rehearsals, and full rehearsal (where possible) will guarantee that the mission get off on the right foot. Number your chalks, serials and lift for enhanced command and control.

ALWAYS REMEMBER THE IMPACT OF WEATHER. HELICOPTER PERFORMANCE IS DRASTICALLY AFFECTED BY WINDSPEED, TEMPERATURE AND HUMIDITY. (SEE DESERT ONE).

The Coveted U.S. Army Air Assault Badge

AIR ASSAULT!!

NEXT MONTH

We will change missions (focus) next month. Our next article starts a mini-series on operations we term tactical enabling operations. Just as the name suggests, these are operations that set the conditions (enable) for a unit to conduct another operation. This may be offensive, defensive or retrograde in nature. Without success in these enablers there is little possibility for accomplishment in the larger scheme of things. In the upcoming months, we will discuss enablers such as passage of lines, relief in place, encirclement, etc…. As is our Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) we will get into the details that will assist you on your battlefield. We will begin the mini-series with the extremely challenging passage of lines.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks