Tactics 101 038 – Air Assault

Air Assault

"The art of war is, in the last result, the art of keeping one’s freedom of action"

LAST MONTH

In our last article, we focused on transitions. As we discussed, in the majority of battles, there are windows of opportunity that present themselves to a Commander. These windows of opportunity may enable a Commander to seize the initiative away from his opponent. Conversely, these windows of opportunity may provide the Commander the ability to simply get out of a bad situation. In both cases, it takes the wise Commander to first understand the window is open and then to act upon it.

In the previous article, we provided you some ways on how you can be that wise commander. We specifically answered the following questions: 1) What is a culmination point? 2) How do you know when a unit has culminated? 3) How do you transition effectively from defense to offense? and 4) How do you transition effectively from offense to defense. We hope the article provided some significant takeaways you can utilize on your battlefield.

THIS MONTH

Beginning this month, we will begin a series of articles on air assault operations. Truly, any army possessing this capability and then possessing the ability to effectively utilize the capability is a formidable foe. During our series, we will cover all facets of air assault operations. This will include planning, preparation, and execution.

To set the conditions, we will focus this article on a general overview of air assault operations. This will include a brief history, a little doctrine, a little language, and describing what air assault can do for you and just importantly, what it cannot achieve. For those of you who have been associated with any air assault operation; you know how challenging it is from start to finish. For those who have not; I believe you will quickly admire all those who do it for a profession! Let’s begin!

A BRIEF HISTORY

Mobility has always been a key military concern. Generals and Soldiers alike worry about how they will get around the battlefield. Innovations in mobility invariably impact the way battles are fought. The first concern was tactical mobility—the ability to move Soldiers and small units around during engagements and battles. Tactical mobility solutions that evolved were cavalry, chariots, and tanks. The next level of concern was operational mobility—the ability to shift forces between battles and engagements. Innovations in the operational realm include the train and riverine troop carriers. Lastly there is strategic mobility—the ability to move between theaters. Strategic mobility innovations were troop ships and strategic airlift. Air assault was an attempt to overcome terrain at the tactical and later operational level. It has been a revolutionary method of mobility and has been a true combat multiplier in modern warfare.

Air Assault was born in the years immediately preceding the Vietnam War. The army was wrestling with the looming dilemma of jungle warfare. Light infantry, long the traditional jungle war-fighter, moved slowly and was plagued by tropical maladies. Paratroopers took time to prepare and required air force partners. Jumpers also required suitable drop zones. On the other hand, Mechanized infantry and armor were hopeless in swamps, bogs, and triple canopy rain forests. Obviously, there was a significant void that needed filling.

The answer seemed to lie in a new capability uncovered during the Korean War—the helicopter. Some forward thinkers wondered what might happen if the helicopter’s role was expanded beyond its introductory Korean role as an air ambulance. The helicopter escaped the natural hindrance of geography, rapidly extracted the wounded from the battlefield, and then transported them to a Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals (MASH). If helicopters could transport casualties from the field, then why couldn’t they move fighters to the field and within it?

The first problem was the machine was itself. The old Korean ‘erector set’ Medical Evacuation (MEDEVAC) chopper only carried two wounded troops on each skid. This was obviously not a viable troop load. To work, the troop assault helicopter had to carry a squad at least. This eventually led to the UH-1 Huey. This was the bird that hopscotched all over Fort Benning, Georgia, with the test division, the 11th Air Assault Division. The Benning trials proved the rotary wing concept.

The helicopter allowed dismounted troops to move rapidly from point to point through the jungle. Its’ ability to move above the jungle enhanced troop survivability by removing them from the disease ridden tropical environment and brought them to the decisive point fresh and ready to fight. It overcame the airborne drop zone problem in that a guided insertion into the landing zone allowed for a smaller landing zone. The air assault trials vindicated a new form of warfare—one that promised expanded mobility, rapid response, and the warrior’s dominance over terrain.

The 11th Air Assault concept was fielded in Vietnam as the newly minted 1st Cavalry Division. They faced their historic first test in the Ia Drang Valley in November 1965 at LZ X-Ray and Albany. Hal Moore’s battle at LZ X-Ray was the one that showcased what air assault could do. He put troops on the ground where they were needed and his support inserted artillery batteries where they were needed. It was clear the helicopter and air assault were now a permanent addition to the war making repertoire.

The combination of aviation and infantry along with other members of the combined arms team is not new. The helicopter is just a new and more precise delivery platform—having progressed from gliders to planes to choppers. The air / infantry mix forms a powerful and flexible team that projects combat power throughout the entire depth, width, and breadth of the battlefield without being restricted by terrain.

AIR ASSAULT – WHAT IT CAN DO

The versatility of air assault comes from its combination of the helicopter’s operational agility with the firepower and tactical mobility of the infantry and its’ close combat capability. Throw in combat support arms and you have a veritable witches brew of combat power. This lethal and versatile combination can be effectively employed on the low, mid, and high-intensity battlefield.

Air assault operations are those in which the assault forces (combat, combat support, and combat service support), using the firepower, mobility, and total integration of helicopter assets, maneuver on the battlefield. They do so under the control of the ground maneuver commander (GMC). They get to the battlefield under the command of the air maneuver commander (AMC). Once on the ground, using vertical envelopment, they engage and destroy enemy forces or seize and hold key terrain.

Air assault operations are not merely aerial movements of soldiers, weapons, and materiel by Army aviation units and must not be viewed as such. They are deliberate, precise, carefully planned, and vigorously executed, combat operations designed to allow friendly forces to strike over an extended distance, over terrain barriers. The goal is to attack the enemy when and where he is most unsuspecting and vulnerable.

Although air assault, airborne, ranger, and light infantry units are much more suited to the role of air assault than are other types of infantry—all infantrymen and their supporting arms counterparts are prepared to execute air assault operations when the situation dictates. Mechanized infantry within Mech and / or Armor heavy divisions can also exploit the mobility and speed of their organic and supporting helicopters to secure a deep objective in the offense, reinforce a threatened sector in the defense, or to place combat power at a decisive point on the battlefield. They can also use them for deep reconnaissance. Like all other forms of infantry, they must retain proficiency in the conduct of air assault operations. This can be a challenge resource-wise.

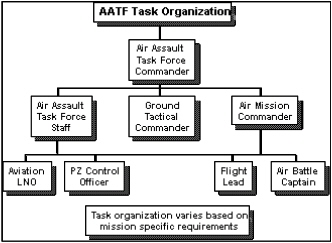

Air assault operations are accomplished by employing an air assault task force (AATF). The AATF is a group of integrated forces tailored to the specific mission and under the command of a single headquarters. It may include some or all elements of the combined arms team. The ground or air maneuver commander, designated as the air assault task force commander (AATFC), commands the AATF. The AATFC may combine infantry companies with aviation assets that can be employed singly or in multiples.

So what can you do with an AATF? The answer is a lot. Helicopter mounted infantry can attack the enemy from any direction. They can drop in on the defender’s head (vertical assault) or can place its’ troops on an assailable flank or to the enemies rear. An excellent option is to insert AATF behind the defender then dissipate into the terrain and infiltrate towards the position. All in all, the great advantage of the AATF is that it can attack the enemy from an unanticipated direction.

An AATF can delay a much larger force without becoming decisively engaged by using Landing Zones (LZ’s) and Pick-up Zones (PZ’s) in depth. Troops enabled by the helicopter can withdraw on moment’s notice or fly in and plug a gap in a flash. Remember that executing a delay, whether with air assault troops or not, requires detailed planning and rehearsal. (We will discuss this planning in later articles).

The heliborne task force can fly over or bypass barriers and obstacles enroute to striking objectives in inaccessible areas. The helicopter overcomes terrain and delivers troops to unexpected locations at unexpected times. The AATF can conduct deep attacks and raids beyond the forward line of own troops (FLOT) or line of contact (LC). They can rapidly concentrate, disperse, or redeploy to extend an area of influence.

An AATF makes an excellent reserve force for the higher unit. Air assault reserves are highly agile and responsive, thus allowing commanders to commit a larger portion of his force to action. Reserves are most effective when they are mobile and possess range—air assault delivers both when planned for in depth. They can react rapidly to tactical opportunities and necessities and conduct exploitation and pursuit operations. This ties into the ability of the AATF to rapidly place forces at emergent decisive points as they are recognized on the battlefield.

Air Assault troops can make excellent scouts providing observation, surveillance, or can screen a wide area. They are excellent for rear area combat operations (RACO), reacting to enemy attacks against logistics and ammunition sites or any other ‘soft’ rear area asset. The rear area is full of combat support and service support units that are vital to the success of the forward combat elements. The rear area is large and is not heavily defended. The enemy can hit the rear in any of a number of places. The AATF makes an excellent quick reaction force to respond to these threats.

Needless to say, the AATF can rapidly secure and defend key terrain such as crossing sites, road junctions, bridges or deep objectives. They can hold these pieces of key terrain and pass armored units through to continue combat operations in depth. This is a traditional task in areas with terrain such as is found in Korea.

They can bypass enemy positions in order to achieve surprise. When timed and planned right, there is no modern surprise more dislocating than facing an unexpected aerial assault. They can conduct operations at night to facilitate deception and surprise and execute fast-paced operations over extended distances. Their mobility even allows them to execute economy-of-force operations over a wide area by holding critical but not decisive terrain for a specified time or until conditions are met that trigger their movement to other objectives. They can provide rapid reinforcement to committed units.

AIR ASSAULT – WHAT IT CANNOT DO

The AATF sounds like the do all/catch all unit, doesn’t it? Well, not quite. As with any force, the AATF has limitations. An air assault task force is light, mobile, and relies on helicopter support throughout any air assault operation. Helicopters may be incredibly mobile, but they are machines and are affected by the weather, maintenance, and can be hindered by battlefield obscuration. The birds themselves are also subject to high fuel (JP4) and ammunition consumption rates. Lastly, remember that the force itself is light once the helicopters depart.

Helicopters are vulnerable to adverse weather such as extreme heat and cold which affects the helicopters allowable cargo load (ACL). Other environmental conditions such as blowing snow and sand can limit flight operations, hinder visibility, or degrade range. This is what happened to the helicopters sent to rescue the hostages in Iran (OPERATION EAGLE CLAW in 1980). The heat and blowing sand degraded the helicopters performance significantly and contributed heavily to mission failure.

Once on the ground, the air assault troops rely on aerial lines of communication (ALOC) for resupply. This is why air assault troops require a ground link up within 48 hours or must have robust air support. Helicopters are vulnerable to hostile aircraft—particularly fast movers—air defense, and electronic warfare action. Don’t forget small arms ground fire. During the initial ground attack during Operation Iraqi Freedom, ground fire wreaked havoc on Apaches conducting deep strikes.

Remember that once the troops get off the birds, they become light infantry with reduced ground mobility. Once inserted, the air assault troopers have all the strengths and weaknesses of any light infantry force. As a light force, they have limited nuclear, biological, chemical (NBC) protection and even more limited decontamination capability.

They are also dependent on the availability of suitable LZ and PZs. LZ / PZ analysis must be thorough. AATF ground troops have little vehicle-mounted antitank weapon support.

Attacks (ground, air, or artillery) during loading and unloading of the helicopters can be devastating. The infantry is also exposed when moving into position or when not dug in. Air strikes can also disrupt an air assault due to the limited array of ADA systems that can be deployed with an air assault task force. Electronic warfare (jamming) hinders operations since air assault is heavily reliant on radio communications for command and control (C2). A major threat to air assault is enemy artillery or other fires that may destroy helicopters and air assault forces during PZ or LZ operations. This is mitigated by proper planning and preparation of the battlefield—enemy air defenses and artillery must be pre-targeted and suppressed during the air movement at a minimum.

TACTICAL EMPLOYMENT

The tactical employment of an air assault task force is different from those of light and other dismounted infantry. An air assault task force is employed judiciously and only on missions that require:

– Massing or shifting combat power rapidly. – Using surprise. – Using flexibility, mobility, and speed. – Gaining and maintaining the initiative. – Extending the depth, width, or breadth of the battlefield.

OPERATIONAL GUIDELINES

An air assault task force is normally a highly tailored force specifically designed to hit fast and hard. They are best employed in situations that provide the air assault task force a calculated advantage due to surprise, terrain, threat, or mobility. The principles of employment are basic guidelines that govern the planning and execution of air assault operations. They are:

- The air assault task force should be assigned only missions that take advantage of their superior mobility and should not be employed in roles requiring deliberate operations over an extended period of time.

- Air assault forces always fight as a combined arms team.

- The availability of critical aviation assets must be accounted for as a major factor in any operation.

- Planning must be centralized and precise while execution must be aggressive and decentralized.

- Air assault operations may be conducted at night or during adverse weather, but require more planning and preparation time in those cases.

- Unit tactical integrity must be maintained throughout an air assault. When planning loads, squads are normally loaded intact on the same helicopter, with platoons located in the same serial. This ensures fighting unit integrity upon landing.

- Fire support planning must provide for suppressive fires along flight routes and in the vicinity of landing zones. Priority for fires must be to the suppression of enemy air defense systems (SEAD).

- Infantry operations are not fundamentally changed by the integration of aviation—tempo and distance are dramatically changed, however.

- Although mechanized infantry units are not frequently employed in air assault operations, they can conduct such operations on a limited scale. Since it would be unexpected, such operations may be the decisive.

- Typical air assault operations conducted by mechanized forces are river-crossing operations, seizure of key terrain, raids, and rear area combat operations. An air assault task force is most effectively employed in environments where limited lines of communication are available to the enemy, where he lacks air superiority and effective air defense systems.

SUMMARY

The versatility of Air Assault spans all three levels of war; tactical, operational, and strategic. Air Assault can be used day or night and can move almost any size unit from squad to Brigade. Even larger movements are possible given detailed planning by experienced units. Tactical air assault can be used to augment ongoing operations within a battle or engagement. Air assault troops can perform maneuvers that no other force can and that can provide opportunities for follow on forces to exploit. They can also have operational impact by picking up and moving formations from one battle to another where their unexpected arrival may have decisive results. On the strategic level, air assault capabilities can deliver Special Forces to remote locations in order to engage strategic targets. Commanders at all levels should consider how, when, where, and for what purpose t use such forces when they are available. When employed properly, they can be decisive. When misused, the results can be disastrous.

NEXT MONTH

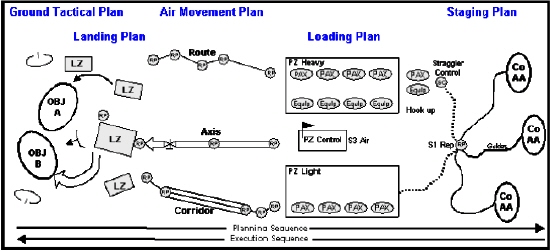

In coming articles, we will discuss the planning, preparation, and execution of air assault missions. The discussion will address the five parts of a comprehensive air assault plan listed below and depicted to the right.

- The Ground Tactical Plan

- The Landing Plan

- The Air Movement Plan

- The Loading Plan

- The Staging Plan