Norwich University’s Gettysburg Staff Ride

001-gettysburgstaffride-001

(Kneeling, left to right) Bill Spoehr, Terry Freese and Johannes Allert; (Standing on near side of fence, l to r) Jim Ehrman, Charles McDonald, Bill Barron, Tom Bottom, Ed Svaldi, Bill Utley, Fred Wieners, Will Windhorst and Judy Christrup; (Standing behind the fence, l to r) Janet Mara, Shellie Garrett, John Votaw, Drew McElroy and Bill Kelly.

Editor’s Note: We recently eagerly jumped at the invitation by Norwich University to send ACG author Jeffrey Paulding along on the Civil War Gettysburg Campaign staff ride conducted as part of Norwich’s outstanding Master of Arts in Military History program. As you’ll read in Paulding’s article, this staff ride is a terrific example of the type of innovative courses available in Norwich’s acclaimed masters program. ACG sincerely thanks Norwich University for the opportunity to accompany their Gettysburg Campaign staff ride. Visit militaryhistory.norwich.edu/ for more information about this outstanding graduate degree program.

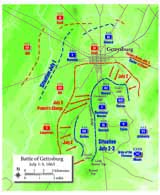

Amid the gently rolling hills of Pennsylvania, for a few hot days in July 1863, the Confederate and Union armies clashed around the crossroads town of Gettysburg. Later, in November 1863, President Abraham Lincoln immortalized the battle in his Gettysburg Address. Already the significance of the battle was being etched onto the American historical consciousness. In a war upon which the fate of the entire nation turned, Gettysburg would be seen as the pivotal point. This previously insignificant collection of farms and fields, low ridges, streams, stony hills and tangled woods would become hallowed ground; each terrain feature assuming a terrible significance, and some, like The Devil’s Den, Little Round Top and The Angle, would achieve iconic status in American military history.

Amid the gently rolling hills of Pennsylvania, for a few hot days in July 1863, the Confederate and Union armies clashed around the crossroads town of Gettysburg. Later, in November 1863, President Abraham Lincoln immortalized the battle in his Gettysburg Address. Already the significance of the battle was being etched onto the American historical consciousness. In a war upon which the fate of the entire nation turned, Gettysburg would be seen as the pivotal point. This previously insignificant collection of farms and fields, low ridges, streams, stony hills and tangled woods would become hallowed ground; each terrain feature assuming a terrible significance, and some, like The Devil’s Den, Little Round Top and The Angle, would achieve iconic status in American military history.

The study of military history is essential to the discipline of military science. The serious student of military history attempts to unravel the confusion of the battlefield, obscured not only by smoke and the fog of battle, but also by the emotions and political interests of the participants. The goal is to understand what really took place. Unless you are a participant in the battle – and even then each player’s part and perspective is limited – you can only begin to understand a battle through accounts of those who fought. Over time, military historians, with their own points of view, assemble a story of the battle from these narratives, complete with the analysis that comes with hindsight. In a battle like Gettysburg, where the fate of the nation was in the balance for three days, the story of what happened has been told from thousands of different viewpoints, first by the men who were there and then by the professional military historians. However, no matter how many of these stories and histories you read, in the end you must go to this hallowed ground, and walk it, in order to understand the tale of the Battle of Gettysburg.

{default}Norwich University, the first private military college in America, has a Master of Arts in Military History program that includes a course on the Battle of Gettysburg which culminates in a trip to the battlefield known as the Gettysburg Staff Ride. Students spend nine weeks studying the battle, interacting online both with their professor (noted military historian John Votaw) and their fellow students before traveling to Gettysburg for three days of walking the battlefield. Recently, I accompanied them. It was a fascinating and educational experience that I recommend to any serious student of military history.

The terrain of Gettysburg is typical for this part of Pennsylvania, with gently undulating ridges and valleys, generally open, interspersed with woods. It is the subtle changes in elevation that make it essential to see and walk the ground first hand. From the top of the observation tower on Confederate Avenue, near the site where Confederate generals James Longstreet and Robert E. Lee planned their assault on the Union left on day two of the battle, it is easy to see with the hindsight of nearly 150 years how things would go awry that day. For Lee and Longstreet, their plan made sense. How different is your viewpoint when walking through The Wheatfield as it inclines gently up to the northeastern wood line, where regiment after regiment of Union troops would emerge the afternoon of July 2 to contest the advancing lines of yelling Confederate troops. The Wheatfield would become a killing field, where thousands would fall in a few hours. Unless you are able to see how compartmentalized the terrain is, it is nearly impossible to understand how this bloody and confusing fight developed and raged on all afternoon.

There are hundreds of narrative plaques and markers to help understand the battle. These key points are further memorialized by statues and monuments erected by the individual regiments and states to honor their heroic contribution during these three days that in retrospect were the most important days of their soldiers’ lives. At each location on the battlefield, now immortalized by a name such as The Peach Orchard, a Norwich student would make a presentation of the events of the battle. Clearly, the students were well prepared by the study of the previous nine weeks for they addressed not only the events of the battle, but key tactical considerations, weapons effects and what the participants of the battle had experienced that day. The Staff Ride leader, Dr. Votaw, enlightened us further by reading aloud the after-action battle reports of the Union and Confederate commanders. Standing on the very ground on which these men fought, listening to them tell of the day’s events in their own words, brought a clarity to the battle not easily found in history books. I marveled at the incisiveness of Confederate General Joseph B. Kershaw’s terrain analysis found in his after-action report of the battle; matching the picture he painted with his words to what I saw as I surveyed the jumble of rocks and trees near Plum Run below Little Round Top.

The students loved it. One of them, a busy executive who had taken a week from his full schedule, told me that for these few days he was transported back in time and forgot all his worldly cares. Each student repeated over and over again how special it was to see the ground. Each echoed the thought: "You have to walk the ground." And as they walked that ground, as many generations of American before them, they re-fought the battle in their mind’s eye. For those who know our nation’s history, the Civil War still evokes subterranean emotions. The student from Tennessee is still proud of the legacy of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest despite his subsequent post-Civil War vilification. The student from Minnesota puffs out his chest as he told the story of the brave charge of the 1st Minnesota Regiment as it stemmed the Confederate tide that threatened to turn a Union retreat into a rout on the afternoon of the second day. For the students, the Staff Ride made history real.

There is a monument next to the Copse of Trees, not far from The Angle, near where Confederate General Lewis Armistead fell, that marks "The High Water Mark of the Rebellion." From this vantage point you can easily see the mile of open ground that Pickett’s charge had to cross on the third day of the battle. The charge ended in disaster, but that was not obvious from General Lee’s point of view on a low ridge opposite. Seeing the ground from both points of view lets you begin to understand how things turned out as they did. The trip to Gettysburg was well worth it.