House of Saddam – Interview with Executive Producer Alex Holmes

Primarily this is a study of the character of a man who changed the course of history . . . his strengths and his flaws.

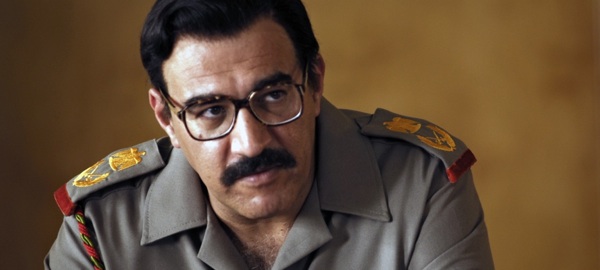

House of Saddam, a four-hour miniseries that debuts on HBO at 9:00 pm Eastern Time, December 7, 2008, examines the repressive Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and the lives of the people who were in his inner circle. It stars Igal Naor (Rendition, Munich) as Saddam and Oscar nominee Shohreh Aghdashloo (House of Sand and Fog) as his cousin and first wife, Sajida Khairallah Tulfah.

A co-production of HBO and the BBC, House of Saddam is more a psychological drama than a simple, chronological narrative. It explores the circumstances within Iraq and within Saddam’s family that contributed to the decisions he made in his dealings with the international community and the Iraqi people. The why is as important as the what.

{default} Many people who knew Saddam and his family were interviewed as part of the research for the series. They ranged from cooks and manservants to politicians and palace insiders. These interviews were then cross-referenced against documents, photographs and home movies left behind by the Hussein family.

Many people who knew Saddam and his family were interviewed as part of the research for the series. They ranged from cooks and manservants to politicians and palace insiders. These interviews were then cross-referenced against documents, photographs and home movies left behind by the Hussein family.

Alex Holmes was the miniseries’ executive producer, writer (with Stephen Butchard) and director on two of its four episodes (Jim O’Hanlon directed the other two). On December 2, Holmes talked with ArmchairGeneral.com in an exclusive interview about the program and his own interpretations of Saddam’s behavior.

ArmchairGeneral.com: What first drew you to this project?

Alex Holmes: Originally, I was researching a film about events in Fallujah in April 2004, the first real outbreak of insurgency in post-invasion Iraq. I had been introduced to some people who had been part of the insurgency in Fallujah, and I soon realized I needed to understand more about the recent political culture in Iraq if I was to understand how these insurgents thought.

That led me to research Saddam. I discussed what I was learning about him and his inner circle with colleagues at the BBC. The more I told them about what I was learning about Saddam’s inner circle, the more they felt that this was the real story that needed to be told—an inside perspective instead of a geopolitical view that news analysis tended to provide. What interested me personally was the way in which the political and the family stories mapped onto one another and were so closely intertwined.

ACG: You seem drawn to stories about people with defects. Your 2004 television movie Every Time You Look at Me is about a character with physical deformities caused by thalidomide. In Flesh and Blood (2002), the protagonists’ parents have severe learning disorders. Did the character of Saddam appeal to you as a filmmaker because he had what might be called a "moral disorder," a sociopathic nature?

AH: Saddam was a very strong person, very charismatic, a strong leader, but ultimately for me his flaws are what defined him. His strengths were undermined by his inability to trust any of the people around him. During his rise to power he felt better able to trust his family than anyone else, so he surrounded himself with relatives who filled many of the most significant government positions. As their authority grew, he became distrustful of them too, removing and killing them one by one. Yes, I would describe the inability to trust as pretty disabling in someone’s character, a "moral disorder" as you say.

ACG: Your television movie The Other Boleyn Girl (2003) didn’t claim to be a historical documentary, but a historical drama that perhaps explores truths rather than facts. You made Dunkirk (2004) as a documentary. Where does Saddam fall between the two?

AH: When you have dramatization of historic events, you always have to find that place where truth and fact overlap. Even in Dunkirk, which was based heavily on first-hand accounts, there was still a need to re-imagine events in order to recreate emotions rather than just recording facts. In House of Saddam, we stuck as close to the facts as was possible, but there were always multiple interpretations of the people and events we discussed. You have to be guided by an understanding of a character, to find a deeper truth, and make your decisions as to how you represent situations on that basis.

ACG: What are you hoping viewers will learn from the program?

AH: Primarily this is a study of the character of a man who changed the course of history. We looked at the workings of his inner circle. We get to see much of how Saddam interacted with the West and the terrible consequences of his regime for the Iraqi people. But ultimately our focus always returns to the man, his strengths and his flaws.

One thing the series does try and do is to provide the family and micro-political background to some of the more significant geopolitical events of his time in power. For example, in the section about the invasion of Kuwait, we had to look at what was going on his family, and the inner circle, as well as the regional factors to get a proper understanding of Saddam’s decision to invade. (Iraq had been economically devastated by the Iran-Iraq War and, in the miniseries, Saddam is depicted as regarding Kuwait’s refusal to cut oil production as betrayal by an Arab brother. — ACG)

ACG: In the miniseries, the Saddam character often makes patriotic declarations about Iraq and seems to genuinely love his country. Shortly before he is captured, he is shown kissing the Iraqi flag. Do you think Saddam came to confuse himself with Iraq and vice versa?

AH: I have no doubt there was both a conscious and an unconscious decision to identify himself with his country. He needed people to believe that any attack on Saddam was an attack on Iraq.

But Saddam took this level of identification between himself and the country to extremes. In Part Two of the series there is a scene in which a sculptor shows him a miniature of the Victory Arch Saddam wanted built to commemorate what he called a victory in the Iran-Iraq War. The arms holding the swords are actual casts of Saddam’s own arms. What is remarkable is that the arms and hands of the actual arch weren’t just representations, they were replicas of Saddam’s arms and hands—right down to the sworls on his thumbprints. That is a very strong example of how Saddam identified himself with Iraq. Later in his regime, he placed an Islamic statement on the flag; it is in his own handwriting.

But Saddam took this level of identification between himself and the country to extremes. In Part Two of the series there is a scene in which a sculptor shows him a miniature of the Victory Arch Saddam wanted built to commemorate what he called a victory in the Iran-Iraq War. The arms holding the swords are actual casts of Saddam’s own arms. What is remarkable is that the arms and hands of the actual arch weren’t just representations, they were replicas of Saddam’s arms and hands—right down to the sworls on his thumbprints. That is a very strong example of how Saddam identified himself with Iraq. Later in his regime, he placed an Islamic statement on the flag; it is in his own handwriting.

ACG: The Saddam character deludes himself into believing he had won the Iran-Iraq War, which was actually more of a bloody stalemate. Later, that same self-delusion leads him to conclude he won a great victory in the First Gulf War. What are you thoughts on this delusional side of the real Saddam’s personality?

AH: Saddam was a man who believed in himself. He was able to conceive events in a way that he wanted. He chose the facts that suited him best and created a story out of them.

That had an impact on how he thought he should be treated by his neighbors. Even more disastrous than his misrepresentation of the Iran-Iraq War was his misinterpretation of what lay behind the decision of Coalition Forces in the First Gulf War to halt their advance into Iraqi territory. He read this as a sign of weakness on the part of the U.S.–led forces. In 2002–2004, based on this misrepresentation, he miscalculated the true intent of the coalition forces this time to actually occupy the country.

ACG: One thing the miniseries clearly does is to provide insight into the women in Saddam’s family. I’m particularly thinking of a couple of scenes involving his first wife Sajida Khairallah Tufah (portrayed by Shohreh Aghdashloo). In one, she tells him he has killed all his true friends, and all he has left are weak men who fear to tell him the truth. In another, she is horror-stricken that the bodies of her murderous sons Uday and Qusay were displayed on international television. Do you think viewers will be able to identify with the women depicted?

AH: I hope so. One thing important thing to do is to make people understand that characters, whatever their historical role, had reasons for what they did and what they feel. Any mother would be appalled at seeing her son’s bodies displayed on television.

In a way, Sajida was the one person who could tell Saddam the truth. Several people I talked with told me she was one of the few people who could be honest with him. They had a very complex relationship.

ACG: Then there’s Saddam’s mother, a paranoid hag who almost makes Tony Soprano’s manipulative mom look sweet. How much influence do you think she had on Saddam’s life?

AH: If you look at her circumstances, the way we told the story, she had to represent an awful lot of history—all of Saddam’s upbringing. She represented the hard way of life when you live in poverty in Iraq. To grow up in Iraqi society without a father, as Saddam did, is exceedingly difficult.

Her character was based on what people who knew her told me about her relationship with Saddam. To survive and raise a son in the circumstances she did she had to be a formidable person, but she had antiquated views of power and loyalty that Saddam was both attracted to and repelled by.

ACG: In an early scene, Iraq’s president Ahmed Hassan Bakr praises his minister Saddam for all Saddam has done for the Iraqi people—building schools, hospitals and the like. Were Saddam’s actions indeed beneficial for his people before he gained complete power?

AH: I think that during the 1970s there’s no doubt Saddam did a great deal to improve the lot of the average Iraqi, such as nationalizing the oil industry, establishing a level of women’s emancipation beyond anything else found in the Islamic world, and so on. He was a social reformer but politically repressive. Ultimately, the political repressive side took over. That is when the true tragedy of Saddam for Iraq became clear.

If you could have included the work of http://www.regimeofterror.com and http://www.husseinandterror.com you could have had a much better movie though this one was good. These two sites were run by people who studied Saddam very closely for many many years.

If you could have included the work of http://www.regimeofterror.com and http://www.husseinandterror.com you could have had a much better movie though this one was good. These two sites were run by people who studied Saddam very closely for many many years.

—————–

You mean a much better propaganda piece. (“Regime of Terror” LOL… As opposed to what? “Regime of Femdom”?)

Sadaam and distrust of staff…

Interesting thing about leaders –natural (childhood alpha males) types (and the few political types left who fit that mold): they don’t trust their underbosses.

This is a “module”(bio chemical compulsion selected by reality) to protect the leader from [sexual] oustings which must come often enough evolutionarily to select for this distrust impulse. A distrust which as said every alpha male type has from Zeus down to kindergarten leaders and chimp and gorilla top dogs.

…The envy module (grass is always greener compulsion and jealousy impulse, related to hunger module itself) is the true root of all evil (and coup’d eta).

Boopy,

What are you talking about propaganda? There certainly has been propaganda about Saddam. It’s been that he had “no links” to terrorism or al Qaeda.