Franco-Thai War, 1941

Defeat in 1940 did not take France out of World War II. If anything, the disposition of its worldwide empire became even more important after the Nazis took Paris. Still possessing a powerful navy, large armies in Africa, and bases around the globe, the French remained a major player, and held key logistical territories that both the Allies and Axis valued.

This was certainly the case for France’s Indochina holdings in Southeast Asia. Encompassing modern-day Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, the colony was squeezed between the three major local powers—Thailand, China and Japan—and offered jumping-off points for penetration into Malaysia and Burma. Indochina’s strategic location perhaps made a war with Thailand inevitable; it certainly guaranteed Japan’s keen interest.

{default}Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries Thailand was diminished as its territory was gradually appropriated by Britain and France. Just prior to World War II, (popularly called “Phibun”) began a campaign to restore what was viewed as Thailand’s lost greatness, in much the same way Mussolini championed a resurgent Italy. Recognizing where power lay, Phibun cultivated stronger relations with Japan. He changed the country’s name from Siam to Thailand (Land of the Free) in 1938 and demanded the return of the “lost provinces,” extreme eastern portions of Thailand ceded to French-controlled Laos and Cambodia in 1904.

After the fall of metropolitan France, Phibun recognized there was an even greater chance Thailand might regain its former territory. While wrangling with Indochina over the disputed areas, Phibun sent envoys to Japan, asking what aid that country might offer if Thailand went to war against the French colony. Though happy to encourage any action that might keep potential enemies off balance (especially one so strategically located as Indochina), the Japanese only offered lukewarm support because Thailand refused to allow unconditional access to its roads and ports for Japan’s campaign against the British in Malaysia.

After the fall of metropolitan France, Phibun recognized there was an even greater chance Thailand might regain its former territory. While wrangling with Indochina over the disputed areas, Phibun sent envoys to Japan, asking what aid that country might offer if Thailand went to war against the French colony. Though happy to encourage any action that might keep potential enemies off balance (especially one so strategically located as Indochina), the Japanese only offered lukewarm support because Thailand refused to allow unconditional access to its roads and ports for Japan’s campaign against the British in Malaysia.

The Japanese had already squeezed concessions from the French for their campaign against China. In early 1940 they attacked and captured Haiphong and areas surrounding Hanoi in northern Vietnam. As part of the armistice, the French governor Admiral Jean Decoux allowed the Japanese to base men along the border with China, which gave Japan control of rail traffic into China, cutting one of the Kuomintang Army’s last supply lines.

Emboldened by these events, Phibun decided to reclaim Thailand’s former provinces by force. In November of 1940 Thais started probing Indochina’s defenses with artillery strikes and border raids. The invasion began in January 1941.

Thailand’s forces were a mixture of western and eastern material. The air force consisted of American-built Corsairs and Curtiss Hawks and Japanese Mitsubishi bombers. The army fielded German Krupp guns and British Vickers tanks. The navy was comprised mainly of torpedo boats manufactured in Italy, but also two Japanese-built coastal defense ships. In all, Thailand fielded about 60,000 men organized around four separate armies.

Even with advance warning, Indochina faced a dire predicament. Though not significantly smaller at 50,000 men (12,000 being European French), the Indochinese army also had the double duty of maintaining order within its own borders. Native rebellions plagued the colony, drawing soldiers away from the front to police the local populace. Against Thai armor Indochina could only field one operational tank company. Their air force was considerably inferior, able to muster 100 mostly obsolete aircraft. Only 15 were “modern” and those were appropriated from a shipment meant for the Nationalist forces in China. This was considerably less than what the Thais possessed, a fact that would tell in the coming battles. To make matters worse, the colony was cut off from the home country. Local shortages ensured things such as oil went to Japan first, and the British prevented Vichy ships from ever reaching the distant colony.

In the first few days of fighting Thai pilots took the skies and never relinquished them, while the accuracy of Thai fighter-bombers surprised French commanders. The ground war was little different. Just a week into the conflict the Thai army gained control of Laos and most of the Mekong River’s western bank.

Cambodia proved more intractable. Thailand sent the bulk of its invasion forces into the disputed Cambodian province of Battambang. Strong resistance from native colonial rifle brigades kept Thai gains to much less than in the Laotian offensive.

On January 16th the French counterattacked in Battambang, at the same time committing to a diversionary assault on islands in the Mekong River and a naval strike against the Thai fleet in the Gulf of Siam.

The Battambang offensive was a disaster. The Thai air wing operated with impunity, and the dense jungle made force-coordination nearly impossible. To compound matters, the French broadcast in Morse code, allowing Thai commanders to listen in on field orders. The French lack of tanks also told, and soon the offensive was in full retreat, fleeing a column of Thai armor.

Only the daring resistance of legionnaires at the village of Phum Preau prevented an unmitigated route. The Fifth Regiment of Legion Infantry brought two 25mm and a 75mm gun to bear against the tanks. Reinforced by a regiment of colonial motorized infantry, the legionnaires destroyed three tanks and forced the rest to retreat.

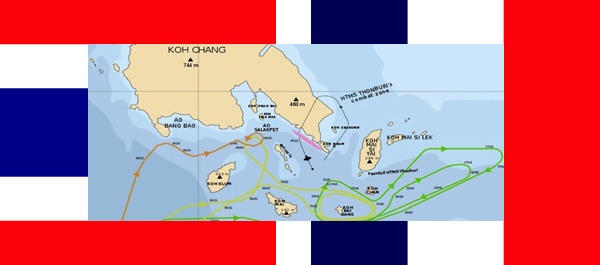

Unexpectedly, the war’s most remarkable battle occurred in the Gulf of Siam.

As support for the southern advance into Cambodia, the Thai navy stationed vessels in the water around the Koh Chang islands. The detachment included three Italian-built torpedo boats and two armored Japanese coastal defense ships, Donburi and Ahidea, with 6”guns.

During the Battambang counterattack, the French hit Koh Chang with the light cruiser Lamotte-Piquet, two sloops named Dumont d’Urville and Amiral Charner, and two gunboats dating from World War I, Tahure and Marne.

The battle’s salvoes began a little after 6:00 a.m. Hardly an hour later the Ahidea ran aground to save itself from sinking after the Lamotte-Piquet inflicted mortal wounds on it. Minutes later, all three Thai torpedo boats went down. The solitary Donburi attempted to flee, but succumbed to fire from the cruiser and sloops. Though it escaped, the ship capsized later in the day, the result of French guns and torpedoes.

The battle’s salvoes began a little after 6:00 a.m. Hardly an hour later the Ahidea ran aground to save itself from sinking after the Lamotte-Piquet inflicted mortal wounds on it. Minutes later, all three Thai torpedo boats went down. The solitary Donburi attempted to flee, but succumbed to fire from the cruiser and sloops. Though it escaped, the ship capsized later in the day, the result of French guns and torpedoes.

The naval success was a great morale boost for the hard-pressed colonials but accomplished little else: the victory was short-lived. Again, the Thai air force proved its worth, and Thai Corsairs forced the French ships to retreat.

Fighting along the border bogged down in late January. At this point, the Japanese decided it was time for the war to end. Its nominal ally in the area, Thailand, had lost the initiative and looked unable to press another advance. Japan showed up in force at the Mekong Delta and “brokered” an accord, though the parties truly had no choice in the face of overwhelming Japanese firepower. Japan allowed Thailand to keep only a portion of the territory it had captured and also forced the Thais to pay restitution to the Vichy government.

What the ceasefire agreement demonstrated was who controlled events in Southeast Asia. Japan made it plain Indochina’s continued independence rested on Tokyo’s whim. Japan’s intercession also allowed it to legitimately increase its presence in the area and gain further access to the corridors that led straight through Thailand to Malaysia and Burma. Phibun, who had hoped for greater cooperation with his country’s Asian neighbor against what many saw as European interlopers, realized Japan had no interest in his nation except for its strategic position. He feared an invasion and later secretly approached the British and Americans seeking aid if Japan invaded Thailand.

Compared to the scale of World War II, the casualties in Indochina were small, with the French coming out the worse. The colonial army suffered 320 casualties, compared to 90 Thais killed on land and at sea.

Compared to the scale of World War II, the casualties in Indochina were small, with the French coming out the worse. The colonial army suffered 320 casualties, compared to 90 Thais killed on land and at sea.

Neither country fared well in the aftermath. Japan invaded Thailand on December 8, 1941. Indochina remained semi-independent until 1945 when the Japanese military—fearing an Allied invasion through Indochina—without warning attacked and killed or captured most of the territory’s armed forces.

The areas of Indochina reclaimed by Thailand were handed back to the French colonial government in 1946 as part of a deal to prevent France from vetoing Thailand’s membership in the United Nations.

About the author:

Stefen Styrsky is a free-lance writer living in Washington, D.C. He has published other military history articles in World at War magazine.

The only quibbles I have is that the caption of Phibun says: “Plaek Pibulsonggram, Hyde Park, New York, 1955.” It should be, London, not New York.

And the name of one of the Thai ships given as “Ahidea” is usually spelt Ayudhya or Ayudia or Ayutthaya, never Ahidea.

Otherwise, good.