France Invades North America in World War II

World War Two evokes images of military forces clashing on a massive, if not continental scale: the D-Day invasion, Leyte Gulf, the North Africa Campaign come immediately to mind in any discussion of the conflict’s battles. Most are also imagined occurring outside the Western Hemisphere. Yet there was action, less expansive events, in other places—even North America.

One such incident was the invasion of two islands off the coast of Canada’s Newfoundland by the Free French. Despites its minor nature compared to what was happening elsewhere, the incident caused a serious rupture among the Allies and threatened an important agreement the United States possessed with Vichy France. It had the potential to dramatically alter the course of war.

{default}France’s surrender in 1940 split the French nation in two. As part of the armistice agreement with the Nazis, the German army was allowed to occupy Paris and France’s northern half, while the French retained control of their country’s southern portion. Interestingly, the French were also allowed to retain civil administration, such as the police and courts, of all of France.

Called Vichy France after the government’s administrative center, this new entity declared itself neutral in the continuing war between Germany and Britain. The Vichy also retained control of France’s colonies and the armed forces outside the mainland, enabling Hitler to concentrate on defeating Britain without having to worry about France’s still formidable navy and colonial armies. Though neutral, Vichy France was ultimately subject to Nazi control, and was believed to provide intelligence and logistical support to the German military.

Called Vichy France after the government’s administrative center, this new entity declared itself neutral in the continuing war between Germany and Britain. The Vichy also retained control of France’s colonies and the armed forces outside the mainland, enabling Hitler to concentrate on defeating Britain without having to worry about France’s still formidable navy and colonial armies. Though neutral, Vichy France was ultimately subject to Nazi control, and was believed to provide intelligence and logistical support to the German military.

Not all of France’s citizens accepted this arrangement. General Charles de Gaulle was in London when France fell. He declared the Vichy regime illegitimate and urged his countrymen to continue the struggle. Those French who answered his call named themselves the Free French (Forces Françaises Libres) and were often integrated into the British military. It was the conflict between the two competing French governments that set the stage for the Newfoundland action.

The United States maintained full diplomatic relations with Vichy France, even recognizing it as the legitimate French government up until 1943. There was the hope that working with the Vichy might discourage them from directly aiding the Nazi war machine. The French colonies of North Africa and the Middle East were key logistical points. By pursuing good relations with Vichy France the American government endeavored to dissuade them from allowing the Germans to use these areas as staging grounds (the armistice agreement did not require the Vichy to do so). There was also the hope a friendly stance now would encourage the Vichy to ally themselves with the US against Germany at the appropriate time.

In pursuit of this goal, the US even conceded to one particular Vichy demand—the neutrality and safety of all French colonies in the Western Hemisphere. The US guaranteed no forces, even American allies, would be allowed to challenge Vichy control of her colonies.

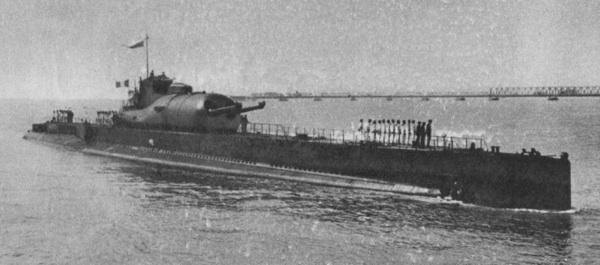

However, at the same time the US was providing support to de Gaulle’s forces. The Free French submarine Surcouf was granted a three-month refit in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. starting in April 1941—a curious allowance since the Americans refused to recognize the Free French as a legitimate organization. The Surcouf was not just some minor French unit. At the time it was the world’s largest submarine. She sported two eight-inch deck guns, weapons usually only installed on cruisers, and possessed a crew of 100 men. She even carried her own reconnaissance seaplane, folded up in a hangar behind the conning tower. The Free French considered it the pride of its operating navy—hardly something that would be overlooked by the Vichy.

America’s precarious balancing act almost collapsed shortly after Pearl Harbor. In late December of 1941 Admiral Emile Muselier, in charge of the Free French navy, assembled off the Canadian coast a small armada of three corvettes—Mimosa, Alysse and Aconit—led by the Surcouf.

The group set sail in cold, stormy seas for what was billed as an independent training exercise. Once out of sight of land, Muselier relayed top-secret orders by line-guns. They were not on a training mission, but one of conquest.

Their goal was the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon five miles into the Atlantic. Some of the last vestiges of French colonies in North America, these islands were now under control of the Vichy government. Muselier intended to retake them for Free France.

St. Pierre and Miquelon were some of the earliest areas occupied in the New World. The first settlers came for the abundant cod fishing, but more recently the islands had been a base for alcohol smuggling to the United States during the Prohibition era of the 1920s. Throughout its history of European settlement the archipelago was always considered of national and strategic importance. The French and British continually passed the islands back and forth, either through invasion or treaty. France regained St. Pierre and Miquelon after Napoleon’s abdication in 1815.

The islands occupied a special place in French history—and a crucial point in North Atlantic shipping. Among the Allies there was the worry the Vichy on the island might provide information about convoys to German U-boats. A radio station on St. Pierre also reportedly broadcast Axis propaganda to the mainland.

Admiral Muselier’s invasion took place on Christmas Eve. The seas were rough and the Surcouf, always an unstable vessel, rolled so badly acid spilled from its batteries, endangering the crew. Unable to enter St. Pierre’s shallow harbor, the giant submarine transferred its boarding personnel to the escorting ships. Landing parties from the corvettes took the Customs House and Gendarmerie without incident. The bloodless invasion was over in fifteen minutes.

Admiral Muselier’s invasion took place on Christmas Eve. The seas were rough and the Surcouf, always an unstable vessel, rolled so badly acid spilled from its batteries, endangering the crew. Unable to enter St. Pierre’s shallow harbor, the giant submarine transferred its boarding personnel to the escorting ships. Landing parties from the corvettes took the Customs House and Gendarmerie without incident. The bloodless invasion was over in fifteen minutes.

When De Gaulle announced the operation’s success, US Secretary of State Cordell Hull was furious.

“Our preliminary report shows that the action taken by the so-called Free French ships at St. Pierre and Miquelon was an arbitrary action contrary to the agreement of all parties concerned, and certainly without the prior knowledge or consent in any sense of the United States Government,” Hull said in a public statement.

Hull even went so far to suggest American or Canadian forces turn out the Free French. Canada actually threatened such an action but never followed through. Just in case, the Surcouf was ordered to prevent any foreign ships from approaching the harbor while the matter was being argued. Though Roosevelt pressed the issue with de Gaulle, it was dropped when de Gaulle ignored him.

Unimaginable as it is now, the threat of a shooting war between the Allies could not be ruled out. Just after France’s surrender the British devastated a French armada stopped at port in North Africa, because British Prime Minister Winston Churchill worried the ships might fall into German hands. As a result of the attack—unprovoked, in French opinion—all French units were ordered to engage the British military. French planes bombed the British base at Gibraltar before it was realized a war between the two allies would not defeat the Axis.

The possibility of the Vichy French taking revenge for the loss of their North American colony could not be ruled out. They still fielded a large army, one that certainly could have made it difficult for the Allies to gain control of North Africa, the Middle East and the Mediterranean. A hostile Vichy navy could have caused trouble for Allied shipping as well.

Fortunately, the Vichy maintained their outward neutrality.

And an event that might have caused serious rift among the Allies was greeted with approval from an American populace now engaged in a battle against worldwide tyranny.

As Churchill wrote in his history of the war, “[Americans] were delighted in this grave hour that the islands had been liberated, and that an obnoxious radio station which was spreading Vichy lies and poison throughout the world, and might well give secret signals to U-boats now hunting United States ships, should be squelched.”

About the Author:

Stefen Styrsky is a freelance writer living in Washington, D.C. He has published other military history articles in World at War magazine.

The article stretches events quite a bit to say the least. This event was a tempest-in-a-teapot and quickly forgotten. It was certainly not a piotential for a fight between allies nor did even remotely threaten tio bring Vichy French forces against the Allies.