Creating the Nazi Marketplace – Book Review

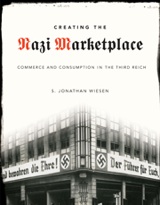

Creating the Nazi Marketplace: Commerce and Consumption in the Third Reich. S. Jonathan Wiesen. Cambridge University Press, 2011. 243 pages, 22 Illustrations. Paperback. $26.99.

Creating the Nazi Marketplace: Commerce and Consumption in the Third Reich. S. Jonathan Wiesen. Cambridge University Press, 2011. 243 pages, 22 Illustrations. Paperback. $26.99.

Even in the midst of WWII, German consumer-oriented businesses retained some autonomy within the Nazi-managed and -organized economy.

While there are other examinations of the Nazi economy, no previous work focused on the business leaders and how they marketed their products from the pre-Nazi era through the post-Nazi years. Professor Jonathan Wiesen’s analysis uses a framework of three lenses to view businesses during this time: continuity with the years of the Weimer Republic, compatibility with Nazi ideology and economic policy, and autonomy from Nazi control:

{default}"The continuity between the pre-1933 and post-1933 economy should not obscure a simple but crucial point: Hitler’s aims could never have been realized without a broad and sustained economic recovery."

Initially, the Nazi party proclaimed itself the champion of ethical business behavior and friend of the consumer. In those early years, pragmatism won over political ideology, which influenced how fast they implemented anti-Semitic laws and rules. A calculated by-product of their focus on military conquest brought full employment to those deemed Aryans. This bought a lot of good will that muted resistance.

"Rather than simply offering a negative story of a homeland beset by political and racial enemies, Nazism offered an affirmative—if corrupted—ethos, based on racial superiority, economic and military might, and the promise of affluence." Nazis publicly used the populist German views of themselves as being more interested in quality over mass production, shopkeepers who could be trusted experts on the products they sold, and advertising that focused on the product’s features instead of denigrating its competitors. To these they added an anti-Semitic and anti-foreign message, blaming them for corrupting German ideals.

As the Nazis became more entrenched and comfortable with their power over the German government and people, they moved from pragmatism to cynical manipulation to ideological purity. For me the most telling—and chilling—example of this move is perfectly captured in the story of the German Rotary organization in Germany, which is the focus of Chapter 3, "Rotary Clubs, Consumption, and the Nazis’ Achievement Community."

At first the Nazis encouraged the Rotary Clubs to freely discuss the "German Economic Miracle" and bring it to the attention of Rotary organizations in other countries, especially the United States. All they had to do was expel their Jewish members. All the clubs complied, with only a few members resigning in protest. Members of the Nazi party were appointed to the various Rotary Clubs to make sure they presented Germany in the best light, especially at the Berlin Olympic Games. Once war started the Nazi government saw no need for the Rotary Clubs, and so it banned them. This brief summary really doesn’t do justice to Professor Wiesen’s descriptions of what happened. This chapter hit close to home for me, as my father has been a member of Rotary clubs in the U.S.

Learning a lesson from the privations and hyperinflation of the end years of World War I and continuing into the Weimer Republic, Nazi economic policy sought to manage wages, prices, production, and consumption even in the worst days of World War II. Their success was mixed, as there were several competing groups in the Nazi government as well as contradictory policies. Companies could not advertise how long they were Aryan and Jew-free, nor could they promote any affiliations with the Nazi party, as that was unfair comparisons with other companies. But companies were expected to extol the Nazi-approved virtues such as consumer thrift. One company was told it could not say of its product, "Still today we offer the same volume to choose from, meticulous service, carpets at a good value, and free delivery" because it was an implied criticism of the government and was unfair to its competitors. The company appealed the decision by the Advertising Council. The Reich economics ministry found in favor of the company, but the propaganda ministry said that the words "still today" had to be removed. As can be seen by this example, companies maintained some autonomy by playing one government group against another.

For a book on economic history, Creating the Nazi Marketplace, is relatively short. The author presents background information, then illustrates the topic with stories about the people who were involved: business leaders, marketers, consumers, and Nazi officials. I found myself stopping several times to think about the stories of those individuals. I found it to be very readable, which may be contrary to people’s expectations of a book on economic history. The bibliography has primary German language sources from the period, as well as post–WWII secondary material and analysis in German and English.

I recommend this book to those who are interested in non-military aspects of WWII Germany, particularly the German home front. While I had read other books on the Nazis rise to power, this really brought home the appeal the party had for German consumer businesses and the limits of Nazi control even at the height of their power.

Steven M. Smith has been an Armchair General contributor since 2010. He has a life-long interest in history especially the Napoleonic and Victorian periods. He was the owner of The Simulation Corner gaming retail outlet in Morgantown, West Virginia until 1983. He is currently a member of the Historical Miniatures Gaming Society and works for Lockheed Martin in Baltimore, Maryland.