Confederate Boys and Peter Monkeys

Some caves were mined during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, as well as during the Civil War, but rarely were American caves mined for saltpeter during peace times. When we examined the amount of potassium nitrate that we were able to manufacture from the dirt of Sinnett Cave, we found that our six pound dirt sample produced only enough potassium nitrate for one charge (65 grains) of black powder. Thus, each fifty pound bag of dirt pulled out of Sinnett Cave had only enough nitrate for eight musket rounds. This is an enormous amount of work for very little reward, and only the emergency situation of the war and the cheapness of the labor made this activity possible and lucrative.Â

At first, many men of military age wanted this job. Although it was dirty, fatiguing, and dangerous, saltpeter mining was still safer than joining the Army of Northern Virginia. Eventually, General Robert E. Lee issued several orders and directives that men were to be removed from saltpeter mining and conscripted into the army instead. Slaves were then proposed for this work. However, many of these cave sites along the “Old Salt Peter Trailâ€Â were targets for Union cavalry raids. Any slaves caught during these raids were often carried off to freedom, and this was a loss of capital investment in the saltpeter industry. So, in a surprising move, the Confederate Nitre Bureau proposed that either free blacks be used, or boys younger than the age of conscription. Thus, if the cave site were raided, there would only be the loss of the wooden bins, kettles, sheds and other property, but not the loss of manpower.Â

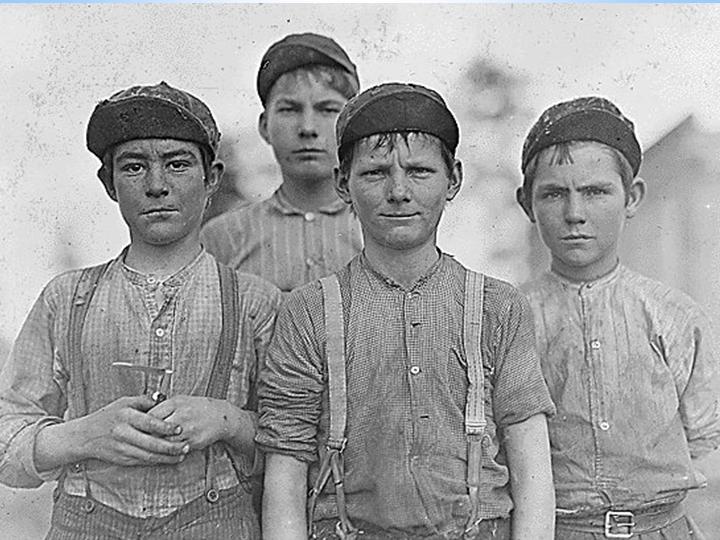

{default}As saltpeter miners, boys were cheaper and expendable. Throughout much of the 19th and early 20th century, boys were preferred for many mining jobs because they were more willing to obey orders from older men, they could be paid less for the same work that men do; and often they came from homes where they were the sole breadwinner, (such as a widow’s home), and thus were desperate to get and keep a job to support their family. These boys were sometimes called “Peter Monkeys,†possibly in imitation of the term “Powder Monkeys,†used for the boys who carried bags of powder from the magazine to the firing deck on navy war vessels. Scrambling up and down the narrow companionways of a ship is probably not all that different from scrambling in and out of the caves.Â

The work of saltpeter mining was very unhealthy. The boys often entered the caves before dawn, and left after sunset. All day they worked in the dark, lit only by the glow of candles or burning splinters of pitch. The dust and dirt in the air often caused lung problems, and the weight of the bags often caused joint and back problems, and frequently hernias. Much of the movement was in confined spaces, and much of the distance to be traveled to and from the dirt site was bent over or by crawling on all fours.Â

The last surviving Confederate soldier in Virginia was John Salling. When he was a “Peter Monkeyâ€, he was only fourteen years old, and for his work he received no pay, and did not wear a uniform. Â

Source: Robertson, G. Alexander. “Vanishing American.†National Speleological Society News. 1954. Volume 12 (4), pages 7-8.

So often the fighting of the men at the front was only possible by the back-breaking work of the boys at home. The role of “Peter Monkey†is a good first-person role to play for boys too young to march in the ranks, and this role shows that boys like them contributed to the cause as well.

Appendix:

Desperate for saltpeter necessary for the making of gunpowder, the Confederacy sent out agents around the South to collect deposits of it. John Harrelson, an agent in Selma, Alabama of the Confederate Nitre and Mining Bureau, advertised the following in the local paper: "The ladies of Selma are respectfully requested to preserve the chamber lye collected about their premises for the purpose of making nitre. A barrel will be sent around daily to collect it."

These poems were soon to written by the soldiers and civilians on both sides:

The Southern version:

"An appeal to John Harrelson"

John Harrelson, John Harrelson, you are a wretched creature,

You’ve added to this war a new and awful feature,

You’d have us think while every man is bound to be a fighter,

The ladies, bless their pretty dears, should save their p** for nitre,

John Harrelson, John Harrelson, where did you get this notion,

To send your barrel around the town to gather up this lotion,

We thought the girls had work enough in making shirts and kissing,

But you have put the pretty dears to patriotic p*ssing,

John Harrelson, John Harrelson, do pray invent a neater

And somewhat less immodest mode of making your saltpeter,

For "tis an awful idea, John, gunpowdery and cranky,

That when a lady lifts her skirt, she’s killing off a Yankee.

A little while later came the Yankee version:

John Harrelson, John Harrelson, we’ve read in song and story

How a women’s tears through all the years have moistened fields of glory,

But never was it told before, how, ‘mid such scenes of slaughter,

Your Southern beauties dried their tears and went to making water,

No wonder that your boys are brave, who couldn’t be a fighter,

If every time he shot a gun he used his sweethearts nitre ?

And, vice-versa, what could make a Yankee soldier sadder,

Than dodging bullets fired by a pretty woman’s bladder.

These poems were discovered by Professor E. B. Smith in the Francis Blair papers in the Library of Congress.

See the webpage accessed on July 10, 2004 here.

A special thanks is given to:

Mr. Dave Dumars, 4th NC reenactment organization (www.4thnc.org)

Organ Cave, Inc. ( http://www.organcave.com/)

Potomac Speleological Club (http://psc.cavingclub.org/).

Pages: 1 2

I noticed you have no comments posted so I thought I should let

you know how much I appreciiated reading this. Marion Smith did

an article on Trinity Nitre Cave and it included the name of my

great-great-grandfather on the payrolls, and I bought his book

also. I live only a few minutes from where he worked and that has

been an amazing discovery for us. I am sharing your article with

my relatives who are participating in our genealogy research,

and your article gives insight into what it was like foim. The year

conscription up to age 40 was made law was the year he went to

work in the cave.

I was about six weeks past my eleventh birthday when John Salling died in my hometown in 1959. I was just beginning a life-long interest in the Civil War. There is much debate about John’s age still today, but for me this lays to rest any debate about his service. I recently found in the OR the directive allowing the hiring of “free persons of color” to work the cave sites. Could you further elaborate on use of “boys under conscription age” ?

Reportedly, Sallings’ father was one of his great-grandmother’s slaves. His mother, was her white grand-daughter. Technically, he could have been considered a “free-person of color.” In an interview shortly before his death, he claimed to recall helping bury his great-grandmother in 1862, so he was a big enough boy to do that. In the same interview he said he only collected dirt from under houses and outbuildings and never worked in the caves.

Thanks for the article.

Glenn

John Salling is my husband’s great great great Grandfather. Thanks for the article and the comment above has helped me try to figure out who his father is. Very helpful!