Command & Leadership

A Classical View of Leadership

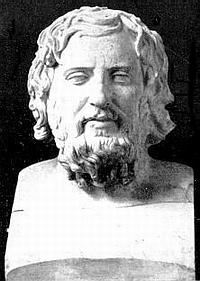

Xenophon

Â

The Classical Greek General Xenophon presented his view of good leadership in Oeconomicus III: "it [is] highly indicative of good leadership when people obey someone without coercion and are prepared to remain by him in times of danger."Â He further stated that the true test of a leader is whether people will remain of their own free will even during times of immense hardship.

The Classical Greeks and Romans developed a framework for the very problem of using coercion to obtain results: pietho (persuasion) as opposed to bia (force). Persuasion was the "natural" medium for a "statesman" or leader to influence humans, since humans were separated from animals by reason. Force, the absence of reason, was the way of the tyrant – unnatural in humans and fitting only for beasts. Xenophon, speaking through Socrates in Memorabilia I states, "persuasion produces the same result without danger in a friendly spirit", while "violence is not to be expected of those who exercise reason: such conduct belongs to those who have strength without judgment."

{default}

Socrates

Â

Plato, in Republic, further develops the pietho/bia discourse to account for the difference between the philosopher-king and the tyrant, thusly:

Pietho              Bia

persuasion        force

leading            coercion

follower/free    subject/slave

just                  unjust

human             beast

natural            unnatural

"Only the true statesman, the ?good, wise and skillful guardian and protector’, who rules for the practical interests and the self-respects of citizens can truly be called the guide and pilot of a nation. Once a leader uses coercion rather than persuasion, he is no longer, by definition, leading. Cicero, De Re Publica.

Even such a "barbarian" as Attila the Hun formed a definite conception of leadership, one that he expected every Hun leader at any level to abide by. This is his encapsulation: "There is no quick way to develop leaders. Huns must learn throughout their lives – never ceasing as student, never above new insights, procedures, or methods."

Leading from the front was considered by the Classical Greeks and Romans to be the only honorable way of leadership. Though not considered appropriate in 20th (or 21st) Century warfare, some 20th Century leaders nonetheless also felt it to be the way of an honorable leader, as noted below:

"We are in a long war against a tough enemy. We must make them [soldiers] tough in mind and body, and they must be trained to kill. As officers we will give leadership in becoming tough physically and mentally. Every man in this command will be able to run a mile in fifteen minutes, in full military pack including a rifle. . . . We will start running from this point in thirty minutes! I will lead!"

General George S. Patton (Age 57!), upon assuming command of the Desert Training Center, Indio, CA, 15 January 1942.

If there is a current that runs through these accounts, it is thus: a true leader leads by consent, by persuasion, not by force, fear, or coercion. The leader who must inflict his command and leadership upon his subordinates does not command, but rather steals his authority from the fear of their hearts.

Another concept often discussed when speaking of command and leadership is cohesion. I present here two definitions of cohesion:

"the feeling of belonging to a team of soldiers who accept a unit’s mission as their mission." – DA PAM 350-2

"the existence of strong bonds of mutual trust, confidence and understanding among members of a unit." – FM 22-100 (1983)

Â

(http://www.belisarius.com/modern_business_strategy/moore/mie_12.htm)

Â

In a further expression and clarification of cohesion and its importance, research has indicated that soldiers in more cohesive units suffer considerably less casualties than other units. In one example, during World War Two, both the 82d Airborne Division and the 101st Airborne Division (who both had very specific, goal-oriented training) suffered markedly fewer casualties than did basic line infantry divisions (who received only the most basic, often vague, training). In another example, similar units of the Israeli Defense Forces suffered similarly differing casualty rates in both the 1973 Yom Kippur War and the 1982 invasion of Lebanon.Â

Cohesion flows from leadership and command. An effective leader inspires and encourages his troops, building cohesion, teamwork, and dedication. A commander must inspire leadership amongst his troops. It is a natural progression – the commander so acts and, when a need or opportunity arises, someone recognizes and addresses it whether a junior officer, top sergeant or private. The sort of command and leadership they have experienced will bring forth in them both the recognition of the need for action, and the professionalism and motivation to take the action. In action, this will come as no surprise to the commander. By his leadership, he expects his troops to step up in such situations, without having to tell them. Why? Because it is what he would do, and by his actions, he inspires his troops to do the same.Â

Building from camaraderie, espirit de corps, and fellowship, a soldier views his fellow soldiers to be an extended family, a brotherhood, and he would no more betray or fail them than his own family. And so when the need for action presents itself, he steps up to the bar and addresses the need to the best of his ability. Thus are heroes sometimes made. But, hero or not, the soldier derives pride and satisfaction for his actions, for he knows that, by his actions, he has preserved the safety and security of his brothers, leaving them ready to fight another day.

Further Reading