A Journey to World War II Battlefields Part 7: How an Incredible Piece of Luck and American Fighting Spirit Saved the American Beachhead at Salerno

Editor’s Note: This article is the seventh installment in a series on World War II battlefields by Carlo D’Este. Please click on the following links to read Carlo’s other articles from this series Tunisia, Kasserine Pass, Malta, Sicily, Biazza Ridge and Messina.

{default}The next stop on our tour of Mediterranean battlefields last year took us on an overnight voyage from Messina to Salerno. Not long after departing Messina our ship passed by the tiny Aeolian island of Stromboli and its famous volcano, nicknamed “the lighthouse of the Mediterranean,” which has been erupting almost continuously for 20,000 years. At night the red glow of molten lava flaring from its crater was easily visible as our vessel passed around the island.

On September 17, we were unable to dock at the small harbor of Agropoli and were taken ashore by the ship’s tender. As we made the brief trip from ship-to-shore I couldn’t help making a distinction between this peaceful morning on the Tyrrhenian Sea and what it must have been like on a similar September morning in 1943 when the Allies invaded the Gulf of Salerno. From Agropoli it was a thirty-minute bus ride to the coastal town of Paestum, the site of the landings by the 36th (Texas) Infantry Division, where it received a horrific baptism of fire that one officer would record as “just plain unadulterated hell.”

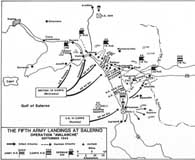

Operation Avalanche was designed to give the Allies a firm foothold in Italy and to isolate German units then operating between the Gulf of Salerno and the Italian “boot.” Avalanche began badly the morning of September 9, 1943 and got steadily worse. Covering an excessively lengthy thirty-mile sector, Salerno quickly became a deathtrap that within a few days nearly resulted in a possibly disastrous decision to evacuate the beachhead.

Operation Avalanche was designed to give the Allies a firm foothold in Italy and to isolate German units then operating between the Gulf of Salerno and the Italian “boot.” Avalanche began badly the morning of September 9, 1943 and got steadily worse. Covering an excessively lengthy thirty-mile sector, Salerno quickly became a deathtrap that within a few days nearly resulted in a possibly disastrous decision to evacuate the beachhead.

Not only was the German Tenth Army anticipating the Allied landings but their artillery was entrenched in the rugged hills overlooking the beachhead and posed a serious threat. Lt. Gen. Mark Clark, the Fifth Army commander, made two critical and nearly fatal decisions before the landings even began. The landing craft were launched at too great a distance offshore (in some instances as much as fifteen miles), thus requiring them to traverse much longer distances to shore and making them more vulnerable to German artillery fire; and Clark, in an effort to achieve tactical surprise, deliberately chose to forego a preliminary naval bombardment under the misguided perception that naval gunfire would unnecessarily attract German reinforcements to Salerno. However, as the Allied naval commander, Admiral Kent Hewitt argued forcefully but fruitlessly, “any officer with a pair of dividers could figure out that the Gulf of Salerno was the northernmost practicable landing place for the Allies. Reconnaissance planes would snoop the convoys; in short, it was fantastic to assume we could obtain tactical surprise.”

From the outset the landings not only took place under heavy enemy fire but the security of the beachhead was immediately threatened by a seven-mile gap between the two assault units: the British 10th Corps and the U.S. VI Corps.

Another major obstacle that would cause untold problems was the Sele River, which abutted the boundary between the two corps. The banks of the Sele were so steep that it could only be crossed using engineer bridging equipment.

Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, still in exile in Sicily after two nearly career-ending slapping incidents in August, was appointed the reserve commander of Fifth Army in the event Mark Clark was killed or captured. When he was briefed on the plan for Operation Avalanche he immediately identified the Sele River gap as a major problem that the Germans were certain to exploit, noting that “just as sure as God lives, the Germans will attack down that river,” which is exactly what they did.

D-day at Paestum was deadly. German panzers, machine guns and mortars created havoc against the lightly armed American infantry of the 36th Division as all attempts to take out the enemy met with repeated failure. Supporting artillery was desperately needed but was unable to land under heavy enemy fire. The toll on the navy was equally heavy. Offshore the hulks of LSTs and LCTs burned after being hit by German gunners. Especially telling were the German defenses along the beaches, defenses which might otherwise have been neutralized had Admiral Hewitt’s advice been taken and the navy permitted to bombard the beaches before the landings.

D-day at Paestum was deadly. German panzers, machine guns and mortars created havoc against the lightly armed American infantry of the 36th Division as all attempts to take out the enemy met with repeated failure. Supporting artillery was desperately needed but was unable to land under heavy enemy fire. The toll on the navy was equally heavy. Offshore the hulks of LSTs and LCTs burned after being hit by German gunners. Especially telling were the German defenses along the beaches, defenses which might otherwise have been neutralized had Admiral Hewitt’s advice been taken and the navy permitted to bombard the beaches before the landings.

On D plus 1 (10 September), badly needed reinforcements began coming ashore. The 157th and 179th Regiments of the 45th Infantry Division, previously in floating reserve offshore, joined the fray. With the exception of one infantry battalion, their mission was to plug the increasingly dangerous gap along the Sele River salient.

One of the primary crops grown on the tenant farms that dotted the landscape in the nearby reclaimed marshlands was tobacco. Its leaves were processed in a massive tobacco factory near the village of Persano. Consisting of five large, red, fortress-like stone buildings, the tobacco factory (the Tabacchificio Fiocche) commanded the roads and river crossings providing access to two highways, both of which were principal German supply and escape routes in this sector of the beachhead.

One of the 45th Division regiments, Col. Charles Ankhorn’s 157th Regimental Combat Team, advanced astride the left bank of the Sele River in order to capture the high ground around the tobacco factory. With the Germans in control of these buildings they were able to block any forward advance along the left flank of the U.S. VI Corps. The tobacco factory became like a dagger pointed at the heart of the seven-mile Allied gap and for six critical days not only foiled the VI Corps advance but threatened to derail the entire beachhead.

There were many desperate battles fought in the Salerno beachhead and the fighting over the tobacco factory symbolized the intensity with which both sides fought to the death. Using the tobacco factory as a wedge, the German 10th Army commander, Gen. Heinrich von Vietinghoff, intended to use his panzers and infantry to drive down the Sele River corridor to Paestum, thereby isolating the two allied corps from one another. By September 12 the beachhead was so tenuous that Clark seriously contemplated the need to evacuate the beachhead.

Over a period of several days vicious battles were fought for the tobacco factory. On September 12 it changed hands twice before being secured by the 157th Infantry. The situation came to a head on September 13 as battles raged not only for control of the tobacco factory but also for the entire beachhead. Across the battered American front came the order: “Hold at all costs.”

U.S. losses grew so heavy and with such disturbing speed that the dead began to pile up at collecting points. The 157th was ousted from the tobacco factory and lost some 500 men. Units were isolated from one another and chopped to pieces, communications were severed, and the battle became a simple struggle for survival. At the end of the fight a mere sixty men were all that was left of one infantry battalion of the 36th Division. The VI Corps commander had no more reserves. “Desperate” became a frequently used but hardly exaggerated word.

U.S. losses grew so heavy and with such disturbing speed that the dead began to pile up at collecting points. The 157th was ousted from the tobacco factory and lost some 500 men. Units were isolated from one another and chopped to pieces, communications were severed, and the battle became a simple struggle for survival. At the end of the fight a mere sixty men were all that was left of one infantry battalion of the 36th Division. The VI Corps commander had no more reserves. “Desperate” became a frequently used but hardly exaggerated word.

As German tanks and infantry penetrated deeper into the Sele River gap, von Vietinghoff became confident that Tenth Army would soon drive the Allies back into the Gulf of Salerno. Sensing victory, he ordered his commanders to throw everything they had into the battle in order to annihilate Fifth Army.

The afternoon of September 13 the German panzer grenadier commander unwittingly let his enemy off the hook. The focus of the battle became the corridor where the Sele and Calore Rivers converge, some two miles south of the tobacco factory, where at first the Germans were successful. A large force of panzer grenadiers and twenty-one tanks had driven a battalion of the 157th Regiment from the tobacco factory, while another powerful force struck a battalion of the 36th Division, forcing it to retire across the Calore River with enormous losses totaling 508 casualties.

The way was now open for the Germans to strike toward the beaches at Paestum and drive a wedge between the two corps that would leave VI Corps outflanked. Their focus was the area of the corridor where the Sele and Calore Rivers converged, some two and a half miles south of the tobacco factory.

The main body of tanks and infantry drove down the corridor between the two rivers intending to cross the Calore River and continue south to Paestum, five miles beyond. The German force was part of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, a unit that had been rushed north from Calabria. Its commanders were unfamiliar with the terrain, and, more importantly, the panzer commander’s map failed to indicate that an all-important bridge had been destroyed. With the steep banks of the river making fording impossible, their once promising advance had instead led them to a dead end cul de sac.

In the open fields across the river was a hastily assembled American force that was determined to prevent any further German advance. It consisted primarily of two field artillery battalions of the 45th Division augmented by a few Sherman tanks and tank destroyers. The U.S. commanders had rounded up every soldier they could lay hands on – clerks, cooks, truck drivers, and even the Fifth Army band – and pressed them into service. This ad hoc force was the only element between the Germans and the sea.

In a scene reminiscent of the Gela counterattacks of July 11, the American gunners, with some support from other nearby artillery units, poured some four thousand rounds into the German force. By nightfall the German commander had found no way around the dead end obstacle he had stumbled into, and, unable to counter the hail of fire raining down on his column, admitted failure and pulled back up the corridor toward the tobacco factory, and the crisis passed. A determined band of gunners, bandsmen, and mixed troops had saved the day. Although the Fifth Army was by no means out of the woods, the failure of the German counterattack on September 13 was a decisive factor in the battle for Salerno.

That night the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment successfully parachuted into the beachhead from Sicily to reinforce the hard-pressed G.I.s, followed the night of September 14 by Jim Gavin’s 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

The tobacco factory was like a revolving door: after first being attacked on the September 11 by the 157th Regiment, it changed hands twice the following day before coming under American control. On September 13 a strong German counterattack recaptured the tobacco factory, and they remained unshakable there for five more days and in so doing were able to block any American advance further inland.

The tobacco factory was like a revolving door: after first being attacked on the September 11 by the 157th Regiment, it changed hands twice the following day before coming under American control. On September 13 a strong German counterattack recaptured the tobacco factory, and they remained unshakable there for five more days and in so doing were able to block any American advance further inland.

Although the area is now well built up, the five stone buildings that comprise the tobacco factory still stand as empty shells symbolic of the bloody battles fought there in September 1943.

Fifth Army casualties at Salerno were 2,149 killed, 7,339 wounded and 4,099 missing, 3,000 of whom were taken prisoner. German losses were comparatively small: 3,472 of which 630 were killed in action.

Author’s note: There were two bloody battles fought for factory complexes during the Italian campaign. The other occurred at Anzio and will be the subject of a future article.

In Part 8 we travel to an Italian town that was so badly fought over that it ceased to exist.

Recommended further reading

Rick Atkinson, The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944 (Henry Holt, 2007).

Des Hickey and Gus Smith, Operation Avalanche: The Salerno Landings, 1943

(Heinemann, 1983).

Martin Blumenson, Salerno to Cassino, United States Army in World War II

(of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Army, 1969).

An old friend, Norm Tucker, a US Citizen flying Spitfires for the RAF would tell us about his Salerno story. The evening before the invasion Norm was shot down and crash landed his spitfire on the beach where the 45th Infantry division came ashore. He hid in a shell hole during the night and then welcomed the GI’s ashore with shouted warnings that he was in fact an American.

Several years after telling this story at a local Rotary club function, Norm passed away. At his wake I saw a photograph taken on the beach at Salerno of his RAF Spitfire. The one he had crash landed. I enjoy Carl’s tour commentary. Keep up the good work.

Peter,

Norm did indeed fly Spitfires, but it was in the USAAF, not the RAF. There were, surprisingly, 2 or 3 American squadrons that flew Spitfires.

KO’M