A Filipino Guerilla’s Story

Editor’s Note: The May 2011 issue of Armchair General magazine features the Great Warriors article, “Filipino Guerrillas, 1942-45,†which presents the story of the heroic resistance of the people of the Philippines to the brutal Japanese occupation during World War II, and how these freedom fighters helped pave the way for General Douglas MacArthur’s forces to return to the islands and liberate the country. This article, by Romulo “Mo†Ludan complements the Armchair General magazine article with the true story of his father, Victorio P. Ludan’s guerilla experiences.

{default}“Here was a people in one of the most tragic hours of human history, bereft of all reason for hope and without material support, endeavoring, despite the stern realities confronting them, to hold aloft the flaming torch of liberty. I recognized the spontaneous movement of a free people to resist the physical and spiritual shackles with which the enemy sought to bind them. It was a poignant moment.”

– General Douglas MacArthur

The Americans Are Coming

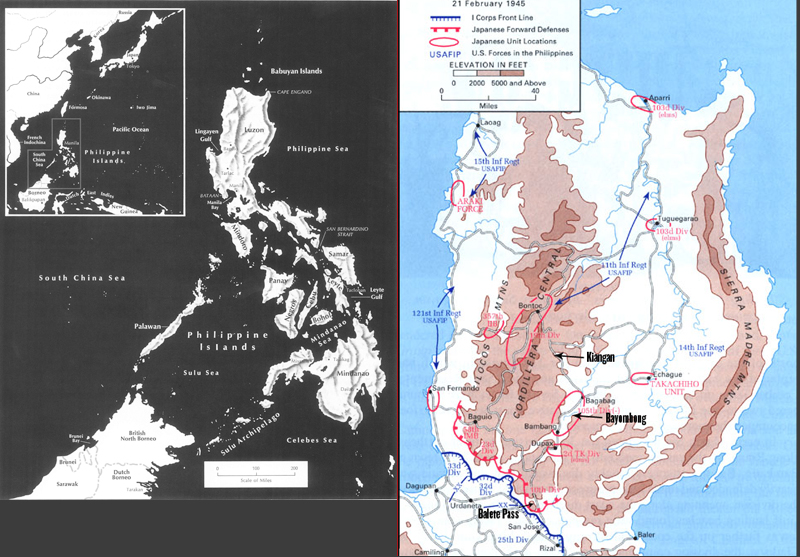

In February 1945, pressed by advancing forces of the U.S. Sixth Army under the command of General Walter Krueger, General Tomoyuki Yamashita, commander of Japanese forces defending Luzon, Philippines, after evacuating a devastated Manila, deployed his remaining 275,000 troops in the mountain strongholds of central and northern Luzon, the Philippines’ main island (40,240 sq miles). Under his personal command was a force named Shobu Group numbering about 152,000 men. General Yamashita knew that he had absolutely no chance of victory. His only objective – to buy time, thereby giving Japan crucial breathing space to prepare for the eventual Allied invasion.

In February 1945, pressed by advancing forces of the U.S. Sixth Army under the command of General Walter Krueger, General Tomoyuki Yamashita, commander of Japanese forces defending Luzon, Philippines, after evacuating a devastated Manila, deployed his remaining 275,000 troops in the mountain strongholds of central and northern Luzon, the Philippines’ main island (40,240 sq miles). Under his personal command was a force named Shobu Group numbering about 152,000 men. General Yamashita knew that he had absolutely no chance of victory. His only objective – to buy time, thereby giving Japan crucial breathing space to prepare for the eventual Allied invasion.

Behind his cordon of superb mountain defenses lay the fertile, rice-growing Cagayan Valley. The 221 mile-long Cagayan River meandered down the valley, emerging from its mountain source in Nueva Vizcaya and heading down to the coastal town of Aparri, off South China Sea. On the west and south of the Valley were some of the steepest and highest mountains of the Philippines, the Central Cordillera and Caraballo range. The rich Valley would feed his troops for several months. It was in this area that the wily Tiger of Malaya decided to make his last-ditch stand. Nestled on the long and jumbled mix of ridges was 3,000 ft high Balete Pass, gateway to the prized valley and heavily defended by the Imperial Japanese Army 10th division.

Behind his cordon of superb mountain defenses lay the fertile, rice-growing Cagayan Valley. The 221 mile-long Cagayan River meandered down the valley, emerging from its mountain source in Nueva Vizcaya and heading down to the coastal town of Aparri, off South China Sea. On the west and south of the Valley were some of the steepest and highest mountains of the Philippines, the Central Cordillera and Caraballo range. The rich Valley would feed his troops for several months. It was in this area that the wily Tiger of Malaya decided to make his last-ditch stand. Nestled on the long and jumbled mix of ridges was 3,000 ft high Balete Pass, gateway to the prized valley and heavily defended by the Imperial Japanese Army 10th division.

Balete Pass was located in the province of Nueva Vizcaya, one of three encompassing the 11,600 sq. mile Cagayan Valley region (the size of Maryland and Delaware combined). The Japanese defenders were constantly harassed by guerilla units of the Northern Luzon guerilla force under the overall command of Colonel Russell Volckmann. General Yamashita, arriving on the Balete front after evacuating nearby Baguio, decided to withdraw the surviving 3,000 troops (out of the 12,000 originally committed) northward to the hilly town of Kiangan.

Balete Pass was located in the province of Nueva Vizcaya, one of three encompassing the 11,600 sq. mile Cagayan Valley region (the size of Maryland and Delaware combined). The Japanese defenders were constantly harassed by guerilla units of the Northern Luzon guerilla force under the overall command of Colonel Russell Volckmann. General Yamashita, arriving on the Balete front after evacuating nearby Baguio, decided to withdraw the surviving 3,000 troops (out of the 12,000 originally committed) northward to the hilly town of Kiangan.

On May 9, 1945, soldiers of U.S. 25th division and a regiment of 37th Division, ably aided by Filipino guerillas, finally broke through the pass and were in pursuit of the retreating Japanese. It was a typical hot tropical day, shortly after Easter, when long lines of starving, haggard Japanese troops in tattered, dirty uniforms, began to stagger toward Kiangan, some 45 miles north of the municipality of Bayombong, the provincial capital and key military command post. Some bedridden Japanese patients were killed by their own doctors rather than fall into the hands of the advancing Americans and Filipino guerillas.

The survivors, many begging for food, belonged to the once proud 14th Imperial Japanese Area Army that triumphantly had marched down Manila’s grand Luneta Park three years earlier. Perhaps out of sheer humanitarian instinct, some Filipino onlookers would quietly peel away from the crowd to hand the emaciated enemy soldiers small cans containing water and dollops of fruits and rice cakes.

A Violin-Playing Guerilla

My elder brother, Arturo, then a spunky 5-year old tot, with older sister, Ofelia in pigtails beside him, caught a glimpse of an officer standing in an armored car. He immediately recognized the officer’s face. He was a colonel in the Japanese Imperial Army and the last to command the crucial military post at Bayombong, which sat astride Balete Pass and the rest of Cagayan Valley. Young Arturo suddenly felt a sense of sadness mixed with a tinge of anxiety at the sight of the fleeing officer. He could recall that, in a strange twist of fate, father’s violin-playing and the colonel’s love of music combined to save dad from certain execution. He would recall the days when the colonel would carry him in his arms like a doting uncle.

My elder brother, Arturo, then a spunky 5-year old tot, with older sister, Ofelia in pigtails beside him, caught a glimpse of an officer standing in an armored car. He immediately recognized the officer’s face. He was a colonel in the Japanese Imperial Army and the last to command the crucial military post at Bayombong, which sat astride Balete Pass and the rest of Cagayan Valley. Young Arturo suddenly felt a sense of sadness mixed with a tinge of anxiety at the sight of the fleeing officer. He could recall that, in a strange twist of fate, father’s violin-playing and the colonel’s love of music combined to save dad from certain execution. He would recall the days when the colonel would carry him in his arms like a doting uncle.

Shortly before the war, my father, Victorio P. Ludan, graduated with a degree in education from the University of the Philippines. His first job was as a schoolteacher in his hometown of Bayombong. In one of the town’s formal dance fiestas, the orchestra leader invited the young Victorio to play his violin. That evening, Victorio was introduced by his sister, Trifena, to her high school classmate, Damieta (“Daming”) Beltran Carbonell. Victorio and Daming got married thereafter and started to raise a family. In December, 1941, war broke out, engulfing the U.S, possession of the Philippines.

Shortly before the war, my father, Victorio P. Ludan, graduated with a degree in education from the University of the Philippines. His first job was as a schoolteacher in his hometown of Bayombong. In one of the town’s formal dance fiestas, the orchestra leader invited the young Victorio to play his violin. That evening, Victorio was introduced by his sister, Trifena, to her high school classmate, Damieta (“Daming”) Beltran Carbonell. Victorio and Daming got married thereafter and started to raise a family. In December, 1941, war broke out, engulfing the U.S, possession of the Philippines.

With amazing speed following their December 22, 1941 main landing at Lingayen Gulf, the victorious Japanese Imperial Army dashed toward Manila, capturing the capital city on January 2, 1942. The Japanese juggernaut smashed northward to capture Luzon’s major towns along the Cagayan Valley to the east, the heavily populated Ilocos region to the west, and the scenic, pine-clad Mountain Province to the center, where lay the 5,000-foot high resort city of Baguio. Seventy-percent of Cagayan Valley’s outlying area remained, however, under the effective control of the Philippine 11th and 14th Infantry Regiments belonging to Colonel Volckmann’s Northern Luzon guerilla force.

With amazing speed following their December 22, 1941 main landing at Lingayen Gulf, the victorious Japanese Imperial Army dashed toward Manila, capturing the capital city on January 2, 1942. The Japanese juggernaut smashed northward to capture Luzon’s major towns along the Cagayan Valley to the east, the heavily populated Ilocos region to the west, and the scenic, pine-clad Mountain Province to the center, where lay the 5,000-foot high resort city of Baguio. Seventy-percent of Cagayan Valley’s outlying area remained, however, under the effective control of the Philippine 11th and 14th Infantry Regiments belonging to Colonel Volckmann’s Northern Luzon guerilla force.

My father continued his teaching job while operating as intelligence gatherer for the guerillas. At the outbreak of the war, he was assigned as sergeant to the Luzon Intelligence Detachment (L.I.D.), 6th Military District (guerilla) based on Panay Island under the command of Major Macario Peralta, Jr. Since his unit was 400 miles away south of Bayombong, he operated with the Nueva Vizcaya-based 14th Infantry Regiment under Major Guillermo Nakar of the famed Philippine Scouts.

In September 1942, Major Nakar was captured by the Japanese. Major Romulo Manriquez promptly succeeded him. Both Nakar and Manriquez operated clandestine radios in the hills northwest of the Bayombong-Palanan line, sending vital information to Allied forces about Japanese shipping and troop movements, and weather. Considered one of the most dangerous jobs during the Japanese occupation, operating radios eventually grew to a network of 169 transmitters. By January 1945, when the U.S. return to the Philippines was in full swing, they were sending MacArthur’s HQ 3,700 reports a month.

In September 1942, Major Nakar was captured by the Japanese. Major Romulo Manriquez promptly succeeded him. Both Nakar and Manriquez operated clandestine radios in the hills northwest of the Bayombong-Palanan line, sending vital information to Allied forces about Japanese shipping and troop movements, and weather. Considered one of the most dangerous jobs during the Japanese occupation, operating radios eventually grew to a network of 169 transmitters. By January 1945, when the U.S. return to the Philippines was in full swing, they were sending MacArthur’s HQ 3,700 reports a month.

Next to teaching which ran deep in the family (his father was one), Victorio’s other passion was playing the violin. He did this mainly for private relaxation and for entertainment at the family’s Sunday gatherings. His cousins, aunts and uncles, who included the old families of Danguilan, Bunanig, Maddela and Panganiban, to name a few, would join in the singing while others played the upright piano, the frame harp and the ubiquitous Philippine guitar. Little did he know that the violin would one day have a profound impact on his life.

Dr. Arturo C. Ludan Recalls

My brother Arturo, today nearing retirement as a pediatrician, remembers almost 66 years to the day: “My father, Victorio, affectionately called ‘Toyung,’ secretly worked with the intelligence unit of Major Nakar’s guerilla outfit. Nobody in town knew about his role. Hence, he was allowed to move around freely while using his teaching job as cover.

The Japanese headquarters was just around the block from our house. The 2-story ancestral home stood directly across the street facing the lateral section of centuries-old St. Dominic Cathedral. The iconic church was built in the 1700’s under the direction of Spanish Franciscan friars. To this day St. Dominic has been able to retain its distinctly Spanish colonial architecture.

The Japanese headquarters was just around the block from our house. The 2-story ancestral home stood directly across the street facing the lateral section of centuries-old St. Dominic Cathedral. The iconic church was built in the 1700’s under the direction of Spanish Franciscan friars. To this day St. Dominic has been able to retain its distinctly Spanish colonial architecture.

In time Victorio’s reputation as a popular violin player reached the ears of the local Japanese hierarchy. Thus, on Sundays, as many as five Japanese officers led by their commander and smartly dressed in military uniforms, would visit our house. To the delight of the Japanese officers, Victorio obligingly played his favorite violin encore pieces, which included Jules Massenet’s Meditation de Thais, Vittorio Monti’s Czardas, Manuel Ponce’s Estrellita, Georges Bizet’s Habanera, and a sprinkling of contemporary music. This became a regular weekend rendezvous. In the process, Victorio cleverly picked up bits and pieces of information which he secretly passed on to his guerilla unit handlers.

In time Victorio’s reputation as a popular violin player reached the ears of the local Japanese hierarchy. Thus, on Sundays, as many as five Japanese officers led by their commander and smartly dressed in military uniforms, would visit our house. To the delight of the Japanese officers, Victorio obligingly played his favorite violin encore pieces, which included Jules Massenet’s Meditation de Thais, Vittorio Monti’s Czardas, Manuel Ponce’s Estrellita, Georges Bizet’s Habanera, and a sprinkling of contemporary music. This became a regular weekend rendezvous. In the process, Victorio cleverly picked up bits and pieces of information which he secretly passed on to his guerilla unit handlers.

“This went on for some time until one evening, a group of Japanese soldiers, brandishing guns and rifles and led by an officer, suddenly appeared at the doorstep of our house. They brusquely demanded to see Victorio. Without any explanation and much to our horror, they forcibly took him away and led him down to an undisclosed location. We learned later that he was taken as a prisoner of war. A Filipino collaborator squealed to the Japanese authorities on Victorio’s covert intelligence-gathering role. I remember following my dad and his escort that night until they entered a schoolhouse, past St. Dominic, that served as an army stockade.

“In the ensuing months, we gathered horror stories of how the Japanese would torture their prisoners, Victorio included. The most horrible was the ‘water torture treatment,’ where they would force the prisoners to gulp down large amounts of water. Afterwards, while the prisoners were on a supine position, a soldier would jump on their bellies and water would gush out from their nose, mouth, etc. The imprisoned guerillas would try to sleep standing up against the wall, sometimes on top of each other’s shoulders, for several seemingly endless hours.

“Under unbearable torture, Victorio confessed to being a guerilla intelligence operative and was promptly sentenced to death. Japanese authorities however had not been able to pinpoint his official unit which was in faraway Panay. Throughout the Japanese occupation, Major Peralta, Jr. controlled most of the 4,440 sq. mile island with the exception of the large port city of Iloilo. As the Japanese prepared Victorio for execution, the arrival of a Japanese commander, who, as it turned out, loved listening to classical violin music, changed things around.” Arturo continues:

“After the war, Victorio wrote his war story entitled My Violin Saved My Life, published in The Philippine Free Press, a popular English language monthly magazine patterned after The Reader’s Digest. The article won a ‘First Person Story’ monthly award. In fact, his life story appeared in Ripley’s Believe It Or Not. Later publications, including some popular Tagalog language newspapers, would, from time to time, feature Victorio’s story in their Sino Sila (Who’s Who) section. It was too bad that the family had neglected to keep a copy of this historical episode of his life. Yet Victorio was a hero in the true sense. He, with the loving support of mother, risked his life to defend the country as best he could. He did it in his own quiet and stoic way. Until the day he died in 1978, he would rarely talk about the torture and deprivations he suffered during those dark days. I remember while growing up that, whenever my younger brother and I would get queasy and complain about pain, Victorio would look at us and, in a reassuring voice, try to calm us by simply saying, ‘Sons, you don’t know what pain really is like. C’mon, you’re big, brave men now. You can handle whatever pain comes to you like I did when I was a young man.’”

“After the war, Victorio wrote his war story entitled My Violin Saved My Life, published in The Philippine Free Press, a popular English language monthly magazine patterned after The Reader’s Digest. The article won a ‘First Person Story’ monthly award. In fact, his life story appeared in Ripley’s Believe It Or Not. Later publications, including some popular Tagalog language newspapers, would, from time to time, feature Victorio’s story in their Sino Sila (Who’s Who) section. It was too bad that the family had neglected to keep a copy of this historical episode of his life. Yet Victorio was a hero in the true sense. He, with the loving support of mother, risked his life to defend the country as best he could. He did it in his own quiet and stoic way. Until the day he died in 1978, he would rarely talk about the torture and deprivations he suffered during those dark days. I remember while growing up that, whenever my younger brother and I would get queasy and complain about pain, Victorio would look at us and, in a reassuring voice, try to calm us by simply saying, ‘Sons, you don’t know what pain really is like. C’mon, you’re big, brave men now. You can handle whatever pain comes to you like I did when I was a young man.’”

“The Hour of Your Redemption is Here!”

On October 20, 1944, speaking from the invasion beach at Leyte Gulf where his forces had just landed, returning him to the Philippines as he had promised, an emotional General Douglas MacArthur began to deliver his long-awaited address: “People of the Philippines. I have returned. By the grace of almighty God, our forces stand again on Philippine soil… the hour of your redemption is here!”

Later, under the watchful eyes of Japanese occupation officials, Yale-educated and the only Filipino recipient of a doctorate from the University of Tokyo, President Jose P. Laurel of the Japanese-sponsored Philippine Republic, gave an equally stirring speech to the grieving nation. He ended it with a deftly placed hint of good things to come echoing MacArthur’s phrase that he slipped past Japanese censors: “Have courage, my dear countrymen, your unhappiness will soon be over. Surely, the day of redemption is dawning.” (Dr. Laurel’s eldest son, Jose, Jr. was Victorio’s classmate and seat mate at the University of the Philippines – students were seated alphabetically according to surnames. After the war, the elder Laurel was granted clemency and Jose, Jr. went on to become a distinguished Speaker of the House.)

The reassuring news had not yet reached most Filipinos. But one of the guerilla runners with the 14th Infantry Regiment made it to Bayombong, carrying the important message. He wanted to relay the news to Victorio that General MacArthur and President Sergio Osmena had returned and that the invasion to liberate the Philippines was in full swing. Happily, Victorio would play, as usual, both Japanese and American melodies during the Sunday soirees. But that late Sunday afternoon, he tweaked his repertoire to include a medley of three new pieces (American, Filipino, and Japanese) for the concluding two minutes of his performance. The first two were Stars and Stripes and Mabuhay (Filipino for “Long Live”) followed by the third, Sayonara (Japanese for “Goodbye’). The first two were intended to announce to his neighbors that General MacArthur, accompanied by Philippine Commonwealth President Osmena, was coming. The third would let them know that the Japanese occupation forces were being pushed back by MacArthur’s forces.

For the next couple of months, Victorio would play his popular repertoire and concluded each performance with the rousing 3-piece medley. On December 20, 1944, the dreaded Kempeitei (Japanese counterpart of the Nazi’s thuggish Gestapo) arrested Victorio and took him and his violin away. After being interrogated and tortured for several weeks, Victorio confessed to being a guerilla intelligence operative. He was convicted and sentenced to the gallows. On New Year’s Eve, the new commander learned of Victorio’s violin-playing and arranged for him to play several Japanese tunes. Victorio played the violin like he never played it before, with consummate passion. He concluded his performance with an emotional rendition of Sayonara, painfully aware that the clock was fast ticking and that soon he would say his last “Goodbye” to his wife and young children.

The western-educated Japanese colonel was apparently taken by Victorio’s violin-playing. The Japanese songs Victorio played were dear to his heart. They evoked fond memories of the colonel’s wife and family back home in Japan. After Victorio’s masterful performance, the colonel slowly rose to his feet. He reached for Victorio’s hand to thank him. With that, he gently picked up the violin and carefully handed it back to him. The colonel turned to his aide and told him to rescind the order for execution. He then declared to a stunned Victorio “You are free to go and you are a friend.” In the midst of an ugly war, a new friendship between a violin-playing, condemned guerilla and a stern Japanese military adversary with an ear for Western classical music had curiously emerged. Victorio, trying to grasp the sudden turn of events, could only mutter, “Thank you, Sir” The colonel’s aide led Victorio to the door. Clasping his beloved violin close to his heart, he looked up the starlit sky and thanked God. He quietly walked past the creaky old iron gate. “Daming” and a few family members were on hand to greet Victorio and bring him home a free man.

The western-educated Japanese colonel was apparently taken by Victorio’s violin-playing. The Japanese songs Victorio played were dear to his heart. They evoked fond memories of the colonel’s wife and family back home in Japan. After Victorio’s masterful performance, the colonel slowly rose to his feet. He reached for Victorio’s hand to thank him. With that, he gently picked up the violin and carefully handed it back to him. The colonel turned to his aide and told him to rescind the order for execution. He then declared to a stunned Victorio “You are free to go and you are a friend.” In the midst of an ugly war, a new friendship between a violin-playing, condemned guerilla and a stern Japanese military adversary with an ear for Western classical music had curiously emerged. Victorio, trying to grasp the sudden turn of events, could only mutter, “Thank you, Sir” The colonel’s aide led Victorio to the door. Clasping his beloved violin close to his heart, he looked up the starlit sky and thanked God. He quietly walked past the creaky old iron gate. “Daming” and a few family members were on hand to greet Victorio and bring him home a free man.

With Daming was her brother, Bataan Death March Survivor Pedro (“Pete”) B. Carbonell, later Captain (ret.), U. S. Army. After the war, Pete taught chemistry at Iloilo City’s San Agustin University until his retirement. With Pete at the Bataan Death March was Victorio’s younger brother, Pacifico, who succumbed to dysentery during the brutal march. Both were classmates at the University of the Philippines when the war broke out. Pete passed away last year. A cousin, Torcuato “Cato” Ludan of the crack Philippine Scouts, was also a Bataan Death March Survivor. He escaped by furtively sliding down a deep ditch and pretended to be dead. Cato spent the rest of the war as a guerilla operating in Cagayan Valley.

On June 7, 1945, Bayombong fell to elements of the U.S. 37th Division and Filipino guerillas of the 14th Regiment. One of the first casualties of the town’s liberation was our house, which was converted into a vital Japanese communications center before the end of 1944. P-38 fighter planes from General George Kenney’s 5th U.S. Army Air Force streaked out of the blue sky and demolished the house and other enemy installations. Advancing U.S. ground troops and guerilla units in Northern Luzon also received close air support from the Marine Corps Aviation. For the period March 5 to 31 for example, 186 separate missions were conducted by the Marine Corps.

Preparing to lead his troops out of Bayombong, the Japanese colonel was offered protection by Victorio from guerilla reprisal by suggesting the colonel surrender directly to him (Victorio earlier had met with his guerilla leaders about this). But the colonel graciously turned down the offer, saying: “I can’t do that, Victorio. You know that. I have a moral duty to stay with my troops to the bitter end.” He thanked Victorio and grabbed his hand as the two new friends, fighting back tears, said their goodbye for the last time. The colonel was never heard of again.

Epilogue

Author Bernard Norling says it best when he describes in his book The Intrepid Guerillas of North Luzon the immense, unsung contribution of Filipino guerillas, ranging from the major figures of the movement to ordinary citizens. All were united in the struggle to bring freedom back to their homeland: “Much has been written by or about most of the Filipino and American leaders of guerilla resistance to the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, from 1942 to 1945: (former presidents) Ramon Magsaysay, Ferdinand Marcos, and Manuel Roxas; Terry Adevoso, Wendell Fertig, Russell Volckmann, Donald Blackburn, Robert Lapham, Ray Hunt, Edwin Ramsay, and others who have written their memoirs or been the subjects of biographies. All these men succeeded in living through the war (no mean feat in itself). All contributed variously to Allied victory.

“Many less well-known Americans and Filipinos also resisted the enemy, but either they did not survive the war, or they left no records, or they simply returned to civilian life and forgot the war. Thus, it is that their achievements, often brief but significant, that have attracted much less attention.”

One such story was that of a quiet, unassuming, and unsung guerilla named Victorio.

For further reading on experiences of ordinary Filipinos during the Japanese occupation, Click here and here.

Bonus Stories of “The Philippines in World War IIâ€

During the preparation of this article on my father’s experiences as a Filipino guerilla, I uncovered the following fascinating stories that have a “Philippines in World War II†connection.

A Filipino “James Bond�

While reading Norling’s The Intrepid Guerillas of North Luzon, I came across a brief narrative on the exploits of an amazing Philippine Scout named Pvt. Joe E. Tugab. His incredible adventures make him a good candidate for the title of a “Filipino James Bond.â€

“On New Year’s eve 1941, famed guerilla leader, Capt. (later Major) Ralph Praeger, checked over his troops in the town of Aritao, province of Nueva Vizcaya, and noticed that Troop C’s normal strength was only 59 that morning, down from a strength of 89. The missing 30 either had simply disappeared during the arduous six-day hike over the mountains or made it to Bataan and Corregidor.

“But one adventurous (and phenomenally lucky) Scout, Pvt. Joe E. Tugab, who had been wounded on December 10, managed to escape to China on a Japanese ship after Corregidor fell. He then made his way to Chungking, the wartime capital of China, located hundreds of miles inland, and eventually fought in the Papuan and New Guinea campaigns. Ironically, and tragically, Tugab somehow survived the war only to succumb to tuberculosis soon after it ended.” The Tugabs are from Nueva Vizcaya. This is the first time I’ve heard of Pvt. Tugab, who, in all likelihood, was dad’s cousin. Unfortunately, the book was not clear on how exactly Tugab ended up in Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s HQ in far away Chungking, crossed South China Sea, made his way back to join MacArthur’s South West Pacific Area in New Guinea, returned to the Philippines, and helped liberate his home province.

One wonders if the resilient and resourceful Pvt. Tugab ended up playing the role of an unofficial go-between for the stoic Generalissimo and his grumpy American nemesis, General “Vinegar Joe†Stilwell. How did Pvt. Tugab manage to get on a Japanese ship and make his way to Chungking? What various disguises and ruses did he use? How did he talk his way out of being caught? Perhaps Pvt. Tugab spoke fluent Mandarin or was, in fact, on a secret mission for MacArthur’s G-2. One can only wonder. From Aritao to Bayombong to Bataan to Corregidor to Chungking to Papua New Guinea, and back to Aritao, returning as a “conquering” war hero … that seems a hard act to follow, even for James Bond!

Shakespeare-Quoting Japanese Commander in the Philippines

There are numerous accounts of the fascinating military career of General Shizuichi Tanaka, who was sent to the Philippines to take command of the14th Imperial Japanese Area Army in 1942 to 1943.

There are numerous accounts of the fascinating military career of General Shizuichi Tanaka, who was sent to the Philippines to take command of the14th Imperial Japanese Area Army in 1942 to 1943.

After graduating from the Imperial Japanese Army Academy and the Army Staff College, Tanaka was sent to Oxford, where he earned a degree in English literature, studying Shakespeare’s works. Due to his skill in English, he was assigned as military attaché in Washington, D.C. from 1930 to 1932. There he met General MacArthur who was then U. S. Army Chief of Staff. their paths would cross again at a building in Tokyo which miraculously had escaped General Curtis LeMay’s firebombing campaign.

General Tanaka served brilliantly in other posts, including his participation in the June-October 1938 Battle of Wuhan during the China campaign and in WWII. He was, however, bypassed several times due to his pro-Western sentiments. Toward the end of the war, General Tanaka’s last assignment was to guard the Emperor as commander of the 1st Imperial Guards Division. He was instrumental in quelling the rebellion led by Major Kenji Hatanaka, who planned to assassinate the Emperor to prevent him from publicly announcing on August 15, 1945, over the radio, Japan’s acceptance of U.S. surrender terms. Ironically, General Tanaka’s office was at Tokyo’s Dai-ichi , the same one used by General MacArthur during the six-year U.S. occupation of Japan following World War II.

Filipinos Among America’s First Casualties of the Pacific War

Stephen Harding, journalist, author and Senior Editor of Weider History Group’s Military History magazine, reveals an interesting “Philippines connection†regarding America’s first casualties of the Pacific War in his outstanding new book, Voyage to Oblivion: A Sunken Ship, a Vanished Crew and the Final Mystery of Pearl Harbor (Amberley Publishing, 2010). The book is an examination of the mid-ocean sinking by Japanese submarine, I-26, of the unarmed American merchant steamer, Cynthia Olson, on the morning of December 7, 1941. The ship’s entire crew disappeared without a trace, and Harding investigates whether the attack on the Cynthia Olson preceded Japan’s Pearl Harbor strike which would make I-26’s attack Japan’s first shots of the Pacific War. Harding unravels that mystery and presents his extensively researched, well-reasoned conclusion.

The “Philippines connection†in this fascinating story so ably told by Harding is that 23 of Cynthia Olson’s 35 crewmen were Filipino sailors. Their disappearance when the ship sank put them among America’s first casualties of the war – two weeks before Japanese forces invaded the Philippines being defended by General Douglas MacArthur’s U.S. and Filipino troops.

Author: Mo Ludan lives in the Seattle, Washington area, is a longtime Armchair General subscriber, and has frequently contributed to the magazine. His web articles include his virtual tours of MacArthur’s Dai Ichi building Tokyo headquarters and Corregidor.

Bibliography and Suggested Further Reading:

Archival records, collections, and photos courtesy of James Zobel, Curator, MacArthur Memorial, Norfolk, VA.

Boggs, Charles W. Major, Marine Aviation In The Philippines. USMC Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps. 1955

Breuer, William B. MacArthur’s Undercover War. Edison, N.J: Castle Books, 2005.

Guardia, Mike. American Guerilla: The Forgotten Heroics of Russell W. Volckmann. Philadephia & Newbury: Casemate Publishers, 2010.

Hunt, Ray C. and Norling, Bernard. Behind Japanese Lines: An American Guerilla in the Philipines. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1986.

MacArthur, Douglas. Reminiscences Annapolis: Bluejacket Books Naval Institute Press, 2001.

Norling, Bernard. The Intrepid Guerillas of North Luzon. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2005.

Steinberg, Rafael and the Editors of Time-Life Books. Return to the Philippines. Richmond: Time-Life Books, 1998.

Willoughby, Charles A. and Chamberlain, John. MacArthur 1941-1951. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1954.

Acknowledgments

Arturo C. Ludan, M.D. Interview. My Recollection of My Father’s Acts of Heroism as Guerilla Undercover, Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines.

Joel L. Nunez. Credits: Pictures of St. Dominic’s Cathedral, Balete Pass, Municipality of Bayombong, old famly house/lot. Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines

Ofelia Ludan Nunez. Quezon City, Metro Manila, Custodian: Ludan family pictures, documents, collections, archival records.

Lilia Ludan Lorenzo. Greenmeadows, Metro Manila and Vancouver, B.C., Canada Editing, compiling, layout.

Nena Ludan Dizon, Sunnyvale, Calif.

Rogel L. Gacerez, Sunnyvale, Calif.

Ennie C. Salvanera. Scanning and emaling of exhibits. Quezon Province, Philippines.

Copy and Print Store Owner Zahir Faruqi and Staffer Slav Kislyanka for copying, printing, faxing, and performing various types of high tech services.

Excerpt from “The Dawn of Redemption” narrated by Nancy Navarro from an account by Gerardo Cruz, Bayombong, Nueva Vizcaya, Philippines .

I think “freedom†is much dearer to us when it’s taken away. This article by his son Romulo shows that there are certain special people, like Victorio Ludan, a Fillpino, who was willing to put himself in harms way; and at risk of his life in order to regain his freedom and self-respect. It is interesting that we are now seeing many thousands that are attempting to do the same in several uprisings in the Middle East. We’re very far removed now from WWII, but we know we’re not finished with the human endeavor of giving the disenfranchised, poor of spirit, hungry, homeless, and women on this planet their due! We can be thankful that there were a few brave souls like Victorio Ludan who stepped up and who bravely carried the torch towards “freedom†for all of us in every sense that that word implies!

Fantastic true story.

Victorio was a hero for his country and risked his life 3 times.

His music and personality saved his life and his information to the Guerilla’s saved many Filipinos and Americans.

I am glad to read this heroic story of Victorio. It is amazing to learn how his love for music and the violin saved his life. Please continue to print stories of ordinary men like Victorio who risked their lives during World War II.

What a great story about your Dad’s (Victorio’s guerilla) role. Your Dad is a hero and such great deed. Thanks for sharing your story. His love for music saved him and his violin was his greatest weapon and companion in saving his life.

This article about a man that was willing to give his life to eliminate a scourge from his beloved country and to ensure that life returned to the civilized peaceful existence they all enjoyed before the invaders arrived is a tribute to Mo Ludan’s father.

Mo and I are friends and have been for several years. I have heard Mo speak of his father many times. I knew Mo’s Dad was a violinist but this is the first time I was privileged to find out that Mo’s Father was one of the bravest of men during WWII.

Great article about a great man by a great son. What else can I say.

…”He immediately recognized the officer’s face. He was a colonel in the Japanese Imperial Army ….Young Arturo suddenly felt a sense of sadness mixed with a tinge of anxiety at the sight of the fleeing officer. He could recall that, in a strange twist of fate, father’s violin-playing and the colonel’s love of music combined to save dad from certain execution”.

I have often felt that these story’s, frankly of men, women, and children of all ranks, services and nations all have so much in common. As the years lay behind us all the memories of the deeds fade back into those years. This is more then a story of life and death but of humanity in a world that had turned around upon itself. For one brief moment in time,can our fates and futures behold.

Mo your brothers words,tell a tale that sound as clear as a note on your fathers violin.

A well witten article. A very impressive and very exciting war story of Victorio P. Ludan. My father, Hilario G. Esguerra, was a major in the Filipino Guerilla Unit. Because of U.S. recognition of his unit, he was given an educational benefit by the U.S. Educational Administration. He passed the benefit on to me as one of his legacies. This made it possible for me to enter the College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Victorio’s alma mater. In a special safe cabinet at our family home in Manila, his guns are well preserved along with other paraphernalia from his days as a Filipino guerilla fighter.

Hil Esguerra III, M.D.

Stockton, CA

Dear Dr. Hil Esquerra, how did you get your USDVA educational benefits although most of the Filipino guerrillas were not recognized under title 38 section 107, Veterans Benefits?

Dear Redentor C. Lorbes,

The educational benefits were passed on to me by virtue of the fact that my father’s Guerilla Unit was one of the recognized few by the US goverment. Not all units were given recognition by the United States.

I had the privilege of meeting Victorio Ludan’s widow, “Daming,†who retired as English and History schoolteacher, during my visit to their family compound in Manila in 2004. I also met Victorio’s son, Dr. Arturo C. Ludan, noted pediatrician-scientist. At the gathering were the rest of the family and their cousins. One of whom was Dr. Mauricia Danguilan Borromeo, at the time Dean of the College of Music, University of the Philippines. I can see that in addition to being fervent Filipino patriots, Victorio’s family prides itself for its long, distinguished lineage in education and music.

Alexander Odell

Mt. Vernon, WA

Incredible story. So many stories of individual heroism have been lost to time. I am happy that the story of Victorio was published and can be preserved. I was especially touched by the bond Victorio created through his music.

Good article, after 60 years, we still see a teacher become a hero when his country and people need him. Let’s always remember them.

“Author Mo is my first cousin. I was a playful, little 7-year old at the time. I recall that one day with first cousins Nonoy (Wilfredo Ludan Gacerez) and Turo (Arturo Ludan) , the prisoners were outside infront of the church, and they were lined up infront a wooden structure with ropes and gasoline drums filled with water. This is one of the Japanese torture techniques they used to their prisoners infront of the public. I saw a glimpse of “Uncle Toyung” (my mother, Rosita, was one of Victorio’s two sisters) hideously being tortured. I learned later that his Japanese captors apparently didn’t get the information they wanted so my uncle was promptly sentenced to death. Thank you, Armchair General, for helping preserve the memory of my uncle’s act of heroism.

Bert Ludan Abriam

Natick, MA

Congratulations for the publication! So true that there are those that were no longer remembered, I feel our father was one of them due to unfair judgement of a leader. Objecting to a higher rank officer to a surrender to the Japanese, he later found out he was stripped of being a US scout, escaping from the Japanese garrison.Later in life, I met the wife of the said officer in a Minnesota church, while some of us nurses looked after her husband, Windel Fertig.I did not know then the story of our father, who passed on as a Col. in the Phil. military, having been a scout in his early years.Wars…so unacceptable!!

Thank you for this article. It’s like listening to my Lola all over again. I’ve always wanted to write her story as she often tell us about her experiences during the war. I was searching the internet for clues about the characters in her recollections. She’s a medical aide and my Lolo was Captain Fernando Maliwanag (I’m not really sure of the rank) and they both served during WWII in Batangas province. It was my lolo who supposedly recruited her, she’s probably not yet 18 during that time. She just came from Bicol aboard the train full of Japanese, cannot read or write (Lolo just gave her instructions on what for each of the medicines in the huge red cross bag which was as tall as her), ran away because her parents (who were fond of gambling and ignoring her and her siblings) are setting her up for marriage. So, I was looking up in the internet for two prominent names from her story. One is whom she calls Capt. Licopa and the next was Capt. Tanaka. About Capt. Licopa, all I found were 1) List of official guerillas in WWII, LICOPA UNIT. 2) There was a mention of Sgt. Licopa in a book called One out of eleven. Could he be the one our nanay is describing as a sharpshooter and leader of their group who walked the grounds and forests of Batangas? Capt. Tanaka is described by nanay as a very good Japanese soldier. He even played cards with them and gave them a pass to show to Japanese soldiers so that they will not be harmed. She even kept a small wooden box which Capt. Tanaka himself made and gave to her. I’m wondering if this is the same Capt. Tanaka you have featured here. It is unfortunate that nanay’s memory is no longer as vivid as before, now I’m left with my own memory to rely on and relive their stories of courage, strength and compassion during the war. I always ask her if she was afraid back then and she just replied that perhaps because she was still young and thus never afraid, naive of the chaos in our then war-torn country.

Thank you for this article. It’s like listening to my Lola all over again. I’ve always wanted to write her story as she often tell us about her experiences during the war. I was searching the internet for clues about the characters in her recollections. She’s a medical aide and my Lolo was Captain Fernando Maliwanag (I’m not really sure of the rank) and they both served during WWII in Batangas province. It was my lolo who supposedly recruited her, she’s probably not yet 18 during that time. She just came from Bicol aboard the train full of Japanese, cannot read or write (Lolo just gave her instructions on what for each of the medicines in the huge red cross bag which was as tall as her), ran away because her parents (who were fond of gambling and ignoring her and her siblings) are setting her up for marriage….

…So, I was looking up in the internet for two prominent names from her story. One is whom she calls Capt. Licopa and the next was Capt. Tanaka. About Capt. Licopa, all I found were 1) List of official guerillas in WWII, LICOPA UNIT. 2) There was a mention of Sgt. Licopa in a book called One out of eleven. Could he be the one our nanay is describing as a sharpshooter and leader of their group who walked the grounds and forests of Batangas? Capt. Tanaka is described by nanay as a very good Japanese soldier. He even played cards with them and gave them a pass to show to Japanese soldiers so that they will not be harmed. She even kept a small wooden box which Capt. Tanaka himself made and gave to her. I’m wondering if this is the same Capt. Tanaka you have featured here. It is unfortunate that nanay’s memory is no longer as vivid as before, now I’m left with my own memory to rely on and relive their stories of courage, strength and compassion during the war. I always ask her if she was afraid back then and she just replied that perhaps because she was still young and thus never afraid, naive of the chaos in our then war-torn country.

Hello, Sgt. Licopa is my grandfather 🙂

Does anyone know of a Fr. Patrick Magnier, a Catholic priest who was involved with the Guerrillas? He was eventually evacuated via submarine.