A Few Acres of Snow – Boardgame Review

A Few Acres of Snow. Boardgame. Publisher: Treefrog Games. Designer: Martin Wallace. List price $39.99 (can go as high as $100 at some outlets, down from $250 before the second printing).

A Few Acres of Snow. Boardgame. Publisher: Treefrog Games. Designer: Martin Wallace. List price $39.99 (can go as high as $100 at some outlets, down from $250 before the second printing).

Passed Inspection: Well-refined game play takes the idea behind Dominion and creates a spare, cyclic turn that allows branching paths for many options and strategies. The deck-building mechanic elegantly serves a number of purposes, acting as resource pool, economic engine, and military force. Consistently great art throughout plus wooden pieces and clinking coins, with plastic bags to store them in after you’re done. The second edition brings the promise of downloadable scenarios from the publisher.

{default}Failed Basic: The game board itself displays a map that has been stretched and distorted a bit more than necessary to make the geometry of North America bend to the will of the art designer. Power gamers have discovered a "sure-fire" path to victory.

“You are acquainted with England,” said Candide; “are they as great fools in that country as in France?”

“Yes, but in a different manner,” answered Martin. “You know that these two nations are at war about a few acres of snow in the neighborhood of Canada, and that they have expended much greater sums in the contest than all Canada is worth. To say exactly whether there are a greater number fit to be inhabitants of a madhouse in one country than the other, exceeds the limits of my imperfect capacity.”

Voltaire’s Candide, Chapter 23 – 1758

Terribly clever people tend to be attracted to one another like magnets, and such is true of game designer Martin Wallace and his military historian friend, John Ellis. One day John got to talking about his line of research for a new book, and Martin got to talking about a new game he had been playing, and like magic the idea behind A Few Acres of Snow took root and began to germinate. Several years later I find myself in possession of a reprint of the now multi award-winning product, and I am very grateful these shared a pint that fateful day. You can almost feel the concept crystallizing inside the designer’s head as you play, as though he were chipping away complexities to reveal the game laying at rest beneath the surface.

A Few Acres of Snow is a rare game where the simplicity of the gameplay, the rhythms of each turn, are matched beautifully to the historical period and place they hope to model. Set in the mid 18th century, it seeks to involve players in the many machinations that lead up to the fall of Quebec and Montreal to the British in 1759–60. At its core it is a deck-building game, in the same vein as the best-selling card game Dominion (a hat tip to which Martin makes in the manual). Players manage and maintain a stack of Empire Cards, which represent the resources, men, and materiel made available by their mother countries as well as the various towns and cities founded in the New World. But unlike Dominion, A Few Acres of Snow is also a fairly crunchy wargame that treats players to an oft-ignored period of military history.

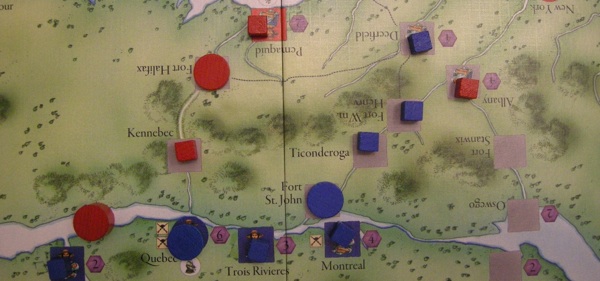

What John Ellis mentioned to Martin was a small quirk of the battlefields that bordered the St. Lawrence River. Because of the ruggedness of the terrain, and the dramatic shifts in climate, the main avenue of approach for both countries was usually a river. A slyly wrought game board models this by putting each player on either side of the great St. Lawrence waterway and forcing them to approach each other through one of only four riverine chokepoints on the map; between Philadelphia and Detroit, New York and Oswego, Newhaven/Boston and Montreal, and between Pemaquid and Quebec. Each step along those routes requires the founding of a new town or fort, a location that must be garrisoned and defended in order to remain a viable beachhead for the next turn’s offensive, and to help itself avoid being flanked or cut off entirely. A simple siege mechanic leads to drawn out conflicts that can easily drain the resources of the entire empire for turns on end. The result is a series of see-saw skirmishes fought far from the civilized coasts, a black powder–filled game of chess across these eponymous acres.

One does not simply walk into Montreal from New York. The handful of roads in the game make their home on the British side, but are primarily located in the area of Philadelphia. So a British player must dip into his hand of Empire Cards for both a bateau (boat) in order to reach Albany and a settler to stay there. Once arrived, a player is rewarded by being able to add to their Draw Deck the Location Card for Albany, itself the key (literally) to moving along the river to Fort William Henry. The fort then opens the door to Ticonderoga, then Fort St. John, etc.

It’s hard to hide your movements from your competition on the map itself, but the true subtleties of the game come in the deck management. As you advance across the map your hand becomes polluted with multiple redundant cards. If you want to besiege a town or launch a raid you need military units to play then and there. But, like a gambler at a cold blackjack table, you can easily go bust for turn after turn pulling nothing but boats and baby-making settler cards from your hand. According to Martin, this is representative of the delay colonial forces had in receiving requested forces and supplies from across the Atlantic.

It’s maddening. Players have a reserve pool of cards they can build up, but a pile of open-faced military cards illustrates your intentions quite clearly. The better solution is judicious use of two unique cards, one on each side of the contest. The corpulent Governor allows a British player to repeatedly select any one or two cards from his hand and return them to the available cards, while the French Intendent charges a small corruption tax to allow you to select one card of your choice from your discard pile.

The economic asymmetry of the conflict goes deeper than the cost of timely reinforcements. During my play-throughs I often found the British player rolling in dough brought in by profitable shipping, while the French player eked out a meager subsistence hocking furs to the elite back home. The British coffers were always comfortably full, but at times the French player was able to cash out for large sums of money that would bankroll a huge offensive. Of far less cost to either side were alliances with the multiple Native American units at play in the game. Either side can enlist the help of these rangers to allow for the harassment of the opponent from a distance, or to parry similar advances.

Two players familiar with and playing quickly can finish a game in 45 minutes to an hour and a half. The British player wins as soon as he takes Quebec, while the French player at all times should be hoping to bring Boston or New York to its knees. Otherwise, the game can end when a player places all their available settlements on the board (signaling the tipping point in the colonization efforts), or when a player has captured 12 points worth of an opponent’s cities or towns (modeling the costly attrition required to convince a country to give up their colonizing and take the next schooner back “across the pond”). The simplicity of the turn, coupled with the myriad actions available to the player, and bolted onto an attractive game board makes this a remarkably efficient game. It is truly deserving of the awards it has earned.

That said, there is an exploitable flaw in the system that some players have used to create a "sure-fire" path to victory as the British. In roleplaying games we call such players “power gamers.” They study the rules religiously, taking it as a personal challenge to create the most powerful character possible by bending the rules without breaking them. A handful of these rules lawyers have found a single, well-timed route to British victory. Their strategies have been validated by the designer himself: The notes to the Second Edition, available for download state: “Some of these folk think there is a particular British strategy which is hard for the French to beat. I have to say that I agree with them.”

Because of this, I can’t recommend this game to power gamers or to those who regularly face that style of player. On the other hand, I hardily recommend the game to players who love to explore a variety of options within a single game. There are reasons why gamers were willing to shell out over two hundred bucks for a copy of A Few Acres of Snow before the second edition became available—despite knowing about the "British gambit." It is that much fun to play.

My advice? Ignore the worn path to victory and let yourself explore the myriad trails through the forests of pioneer-era North America that may lead to triumph. Subtle rules changes in the second edition, related to raids and the reserve pool especially, should be used to make the game more balanced.

Armchair General rating: Based on personal enjoyment, this reviewer would give it a 93% rating, but the exploitable flaw knocks that down to 86%.

Solitaire Suitability (1-5) 1 (Poor). The game is designed for two players to improvise at a number of possible win states using dozens of possible actions and potential strategies. Playing it alone would be a crime.

About the Author

By night Charlie Hall is a writer for Gamers With Jobs (www.GamersWithJobs.com). His relevant interests range from pen-and-paper role playing games, to board games and electronic games of all types. By day he is a writer for CDW Government LLC. Follow him on Twitter @TheWanderer14, or send him hate mail at charlie@gamerswithjobs.com. He, his wife, and daughter make their home in far northern Illinois.

A Few Acres of Snow is a fantastic game. Contrary to the strategic and tactical notes above, through over roughly 100 games, the game is very balanced. However, it requires much different play strategies from the French and English players. Card management skills are critical for both sides but paramount for the French. The player who can know his opponents hand near an upcoming deck shuffle, due to card counting, has a tremendous advantage. Adroit use of the Governor is important for both sides to control the size of their decks.

The English side is somewhat easier to play due to the smaller deck and later the potentially greater military strength. But the vaunted Halifax Hammer can be defeated and delayed successfully by aggressive French counter attacks with both French initial military superiority and importantly by raiding and ambushing. Ambushing can be devastating to the English player while the French player can neutralize the ambush threat with militia – simultaneously building military strength. Meanwhile while the English are occupied with Nova Scotia, the French can be expanding west, selling furs like mad to support the campaign and can “cube out” to beat the English on victory points. One or two mistakes in card counting by the English and a quick French player can be in Boston. Even if the English succeed in holding Halifax, they have neutralized their one advantage – a small deck – by building military. Then they are susceptible to repeated ambushing by good French card counters.

The English can concede Pemaquid to a militarily aggressive French player – the card is useless anyway except as a route to Port Royal or Halifax which the English do not need to win a development victory. Instead the English might build a line of fortresses from Duquense to Albany to Deerfield to Boston/Pemaquid with the intention of “disking out” on the French player. By placing disks on every VP location from Duquense to Boston, without Pemaquid, the English can defeat a “cube development” strategy by the French. An early protracted siege in Pemaquid is to the benefit of the French player as it reduces the size of their deck critically and allows them to build Treasury and military increasing the risk of an assault on Boston.

If the English get sucked into defending Pemaquid early, the French can opt to protract the siege expanding west and disking select locations such as Montreal, Louisbourg and Detroit. the English are then stymied with most of their money producing location cards tied up to defend the siege. If the English player isn’t careful, the French will accumulate a devastating VP total. The French can win without holding Nova Scotia by disking key locations in the West and disking Louisbourg. If the French destroy the garrison at Pemaquid and attempt to settle, they themselves are susceptible to ambushing. While raiding to take a cube or disk can be productive, ambushing is by far the more important tactic and favors the French. Even so, the English can ambush successfully against a growing French military to neutralize them and buy time.

All in all in a “century” of game play, we have found the game to be very balanced but requiring different approaches from English and French players which emphasize their respective initial strengths and weaknesses. Moreover, it requires a quickness and flexibility on the part of both players to roll with the punches. To win against a capable opponent, the French player must manage the deck well and, to that extent, it is harder to play the French. But, who said war was fair?