Tactics 101 060 – Operations Orders

Operations Orders

"Never tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do and they will surprise you with their ingenuity."

General George Patton

LAST MONTH

In our last article, we concluded our mini-series on smoke operations. During our smoke discussion, we provided a general overview of smoke, the utilization of smoke in the offense, and the use of smoke in the defense. In our concluding article on smoke in the defense, we keyed on several areas. These included: 1) How smoke can help the defender in this operation. 2) How a defende’s smoke can impact actions on both sides. 3) The keys to planning smoke. 4) Things to remember in preparing for smoke use in the defense. 5) The execution of smoke in the defense.

{default}THIS MONTH

We will shift gears a bit this month and begin a new mini-series on the Operations Order (OPORD). In our opening article, we will provide you an overview on the Combat Orders and the OPORD. In subsequent articles, we will address what should the 5-Paragraph OPORD include and provide examples of the good, the bad, and the ugly.

If you have wrote your own OPORD or been part of a staff that crafted one; you know it can be a painful process. Because of the pain, there are some who question the need to develop an OPORD. They will say, "You fight the enemy, not the plan." There is certainly much truth in this. However, you must have an understood plan to begin with or you will be fighting chaos not the enemy. Our mini-series will discuss how you can make that OPORD as effective as possible.

INTRODUCTION

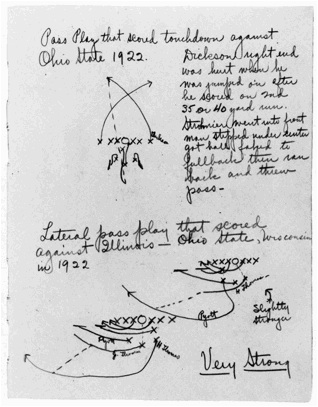

Sandlot to Stadium. Remember when you were a kid playing sandlot football with your buddies? Your QB would draw a play in the dirt and the team would execute it. Then came the high school 20 page Xerox playbook and on to the 700 page NFL playbook. They’re all playing the same game, but they’re all using different tools to plan, prepare for, and play a game. It’s intuitively obvious why. Each successive level is more complicated. The players spend more time training; the opposition is better, the equipment is better, and the stakes are higher. A professional coach wouldn’t last long with a few Xeroxed X and O diagrams. The same principle applies to the use of and ultimate form of operations orders (OPORD).

A Page from the 1927 Playbook of Legendary Football Coach Amos Alonzo Stagg

A quick review of western military history and you can see the growing need for detailed instructions in the Command and Control (C2) process. First we have to break down command and control. Command is the art of providing purpose, direction and motivation. Command is leadership. Control, on the other hand, is the science of monitoring performance, reinforcing success and correcting deviations. Control requires maintaining situational awareness, tracking progress through reporting and shifting effort and resources in order to keep your forces on task. So where does the OPORD fit into all this? The enemy situation defines the problem, while the concept of the operation verbalizes the commande’s vision for the mission. Coordinating instructions, service and support, and signal are all about control. Back to a concise history of western C2 while keeping in mind this is not about weapons or tactics.

Personal Leadership. Combat C2 didn’t change much from Alcibiades to Frederick the Great. Armies were generally small, battlefields were confined, and campaigns were seasonal and limited in scope. The troops were a mixture of untrained peasants and unreliable mercenaries and motives were generally dynastic, centered on the leader who was usually a monarch. This type of fighting required personal leadership from the front, often from a vantage point that could observe the entire battlefield. At this point, most orders were verbal. This might be called the era of command.

Frederick the Great

Decentralization. The French Revolution and the American Civil War shifted C2 from direct and centralized to indirect and distributed. The French Revolution brought nationalism fueled by industrialization—armies grew exponentially. Napoleon’s Grande Armee was too large to move as a single unit given the need to forage. He dispersed to travel and converged to fight, thus requiring subunit orders. The armies of the American Civil War expanded on the above by dispersing to move and fight. The search for the battle that would win it all gave way to simultaneous campaigning on multiple expanded battlefields giving the rise of operational art. Not only were written orders used, often they weren’t even issued face to face as evidenced by the lost Lee cigar wrapped orders recovered by McClellan. The Americans also added two innovations; the railroad for deployment and the telegraph for long distance communications. Command was executed through dispatch riders and couriers. This is the emergence of control.

Robert E. Lee

The General Staff. The Prussians took French massification and American railroads and telegraph use to the next level during the Wars of German Unification. The army was supersized and mobilization critical. The railroads were the key. It took a professional staff of experts to manage the timetables giving rise to the General Staff. Moltke the Elder used the telegraph to send orders to commanders. Orders grew more complex and more necessary given the proliferation of expert information and specialization required to execute operations. WWI leaders took command from the rear to the extreme, becoming chateau generals. The expert staffs emplaced and provisioned the armies and the commanders sat in the rear using telegraphs, telephones, and couriers to send orders forward. Leadership lost touch with the increasingly lethal battlefield—while weapons evolved, C2 stagnated.

The next C2 leap in this period came from the Russian Civil War. The newly minted Red Army faced simultaneous operations on multiple fronts. They didn’t have the resources to do it all at once, so they had to arrange the battlefield over time and space. The result was Aleksandr A. Svechin’s formalization of the operational level of war. Staff experts, weapons lethality, precise mobilization, and the new operational level of war made the written OPORD critical. This was the explosion of complexity.

Command and Control. WWII capitalized on a few last minute innovations from WWI; decentralized infiltration tactics and the tank. The Germans merged the two; added close air support and mobile artillery; and threw in the radio for good measure. The result was Blitzkrieg. Maneuver returned on a vast scale and written orders production was critical to orienting the rapidly moving forces. The orders established the commande’s vision and emplaced the means of control while the radio took command back to the days of Frederick the Great by putting the commander back at the front. America and the Soviet Union expanded on the German concepts by adding operational maneuver and strategic bombing. The US translated the European experience into a naval/amphibious Pacific Campaign. Broad maneuver on multiple fronts was the modern way of war and the synthesis of command and control.

Knowledge War. We’re in an emerging new age. The advent of precise guided munitions, precision targeting, and precision movement (GPS) coupled with new collection capabilities has changed the nature of C2. Today’s commanders win by knowing more than the enemy. We collect, track, analyze, and display everything. This began in Vietnam and was perfected in Operation Desert Storm and Operation Enduring Freedom where coalition knowledge overwhelmed the enemy. The enemy response has been to revert to guerilla warfare, always a good refuge for the weak versus the strong, and exploitation of commercial technology and the Internet. These are new problems with newly evolving solutions. The issue is that the OPORD remains highly relevant and valid if more complex with new Annexes (we will discuss this subject in future articles) being added all the time.

Written instructions became common during the Napoleonic / Civil War period and have been with us ever since. The increasing complexity of the battlefield driving specialization and the need for expertise has made written OPORD’s more important. The emergence of knowledge based warfare has added detail to the orders. OPORD’s are the key communication tool for disseminating lots of information in a single package. It almost becomes a handbook to guide execution over time with mini updates used to adjust course during execution. In spite of all the technological change, it must be remembered that there are still some battlefield constants; it’s still violent, action is purposive, it requires 2-way communications, and its initiative oriented.

The demand for written orders brought about the standardized format. The Staff College at Ft. Leavenworth developed an orders format for the American Army that was approved by the War Department in 1906. The original outline remained nearly unchanged until the mid 50’s. It saw its first heavy use during WWI when it was adopted by the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). Unfortunately, the desire to plan over-rode the desire to communicate. Initially, the staffs lost sight of the purpose and the plan became an end in unto itself. OPORD’s went into excessive detail, micromanaging subordinate units. The effort to issue comprehensive guidance and elaborate orders led to tardy issuance that hindered subunit planning, preparation, and coordination. The result was flawed and confused execution. The AEF gradually ironed out these initial difficulties as they gained experience over time. The temptation to over plan and consume subordinate’s time has been, and continues to be, a real danger.

Garbage in—Garbage Out. Bad orders kill. We experienced this firsthand during a rotation at the National Training Center, (Fort Irwin, California). Our heavy/light brigade consisted of a Mech Task Force, an Armor Task Force, and a Light Infantry Battalion. The missions we received during the rotation reflected a diverse force package. One such mission was to attack though a narrow pass, defended by a security element in order to strike a larger defense beyond it. The pass could only accommodate vehicles in column. The valley walls were lined with infantry and dug in armor over-watching the road laced with wire and mine obstacles. It would take the light infantry to make a path for the heavy forces. The Infantry Battalion was given the mission to clear the pass.

The infantry struck after midnight and fought till dawn. At sunrise, they sent word that the pass was clear. The tanks and Bradleys charged forward looking to get to the main defense as soon as possible. They never got out of the pass. They were hammered by enemy fire and were stopped cold. It turned out the light battalion commander assumed that "clear the pass" meant to remove all the obstacles while the Mech battalion commander assumed it meant to eliminate the enemy. The order had been vague as to the Brigade Commande’s expectations.

Historic examples:

-

Lord Ragland’s order on October 25, 1854; "Ride and bid them take that battery where the guns on the left are frowning there", sent the Light Brigade into the "Valley of Death" at Balaklava.

-

Lee at Gettysburg orders General Ewell to capture Cemetery Hill "if possible". Ewell was accustomed to specific orders from General Jackson. To Jackson, Lee’s order would have meant to seize Cemetery Hill. To Ewell "if possible" meant don’t bother.

On the other Hand … On yet another rotation, our task force was ordered to execute a night attack to dislodge an enemy force from a dominant ridgeline. Night attacks are tough and this was no exception. We had to across a six kilometer stretch of open desert to get to the ridge, all while under enemy observation. The commander issued a detailed OPORD. The ridge was too long to be fully defended and there were too many avenues of approach to cover. He knew there would be gaps and he told us to find a gap. We would use it to envelope the enemy—"to peel" them off the ridge.

Night fell and we got off to a rough start as is common for night ops. Units got scrambled up and the cross talk between commanders made it hard to talk on the radio as the scouts found out when they tried to call us to update the enemy situation. A scout found the gap, but couldn’t cut through the radio traffic to get the word out. He had to flip down to a company frequency where he was able to direct the lead company to the gap he’d found. Nothing needed to be said; we knew what to do and the battle ended in an hour. The clarity of the order enabled a solid win.

Historic Examples:

-

US Grant’s campaign plan sending Sherman to Atlanta while Meade maintained pressure on Lee by threatening Richmond provides the Union with a clear strategy for winning the Civil War.

-

Operation Fortitude, 1944, is so detailed and comprehensive that it completely fools the Germans as to the time, place, and forces to be used, for the invasion of Europe. Fortitude enables the success of the Overlord landings and freezes German reserves during the early critical moments of the invasion thus allowing the allies to seize and fortify a beachhead in France.

Flavors.

Combat orders come in several flavors. This reflects the C2 evolution described above. When Scipio commanded his legion in Carthage, he could give his orders verbally and could direct the action personally, but when Eisenhower invaded Europe, he had to issue the order to his top commanders who issued their own orders and on and on. Once the invasion was in motion it largely went on auto-pilot with minor corrections. To do this requires many types and levels of orders.

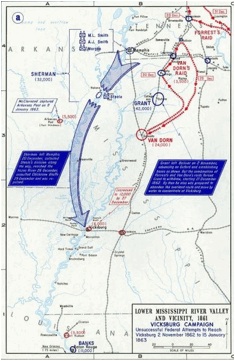

Click map to enlarge.

OPLAN. An Operations Plan (OPLAN) is an order that outlines a campaign. A campaign is a series of battles and engagements that occur over time and space in pursuit of an operational objective that supports a strategic goal. Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign is such an operation that included multiple battles; Raymond, Champion Hill, the Big Black, and the siege of Vicksburg. OPLANS require large staffs and lots of time to prepare. They include multiple detailed Annexes that cover the science of military operations like signal, targeting, logistics, movement and so on …

OPORD. An Operations Order (OPORD) outlines the military actions taken to win a tactical engagement or battle. While an OPLAN would outline the entire Vicksburg Campaign, an OPORD would define the missions for the subunits attacking the enemy at Champion Hill. This is the order we spend most of our time on. It wins the immediate fight.

WARNORD. A warning order (WARNORD) is an alert of an impending mission. The higher commander wants his units to be leaning forward in the foxhole so, when he gets inkling of what’s next, he warns his subunits so they can begin preparation. This inkling comes from the OPLAN which is the overall roadmap. The WARNORD is a partial OPORD that alerts the subunits as to what their next task will most likely be.

FRAGO. A Fragmentary Order (FRAGO) is a partial order that typically adjusts the original order or accelerates the execution of a subsequent mission. For example; if your unit is assigned to take Hill 101 while your sister unit is taking Hill 102, you might get a FRAGO to continue you attack to take Hill 102 because your sister unit cannot. FRAGO’s allow the commander to make adjustments on the fly based on his superior situational awareness.

Characteristics.

None of the orders above will work unless they meet certain basic characteristics. There must be a degree of uniformity and a shared lexicon that ensures comprehension in a single rapid reading. If each commander could "roll his own," there’d be confusion and poor execution. Efficient communication demands a recognizable and widely accepted format that visualizes the concept with maximum comprehension. The format can be neither too specific nor too general. It addresses the infinite variety of unique combat situations while retaining details common to all.

Authoritative. For an order to be useful it must be directive in nature. Lee’s "if possible" violated this principle. The order must clearly specify what is expected of each unit while depicting their role in the overall operation. The order is issued by the authority of the commander and is non-negotiable in terms of the purpose of the operation.

Precise. Tasks must be well defined to be understood. This requires a shared lexicon that provides common understanding. The language of the order is exact. A unit is not simply ordered to attack. This is too generic. It attacks to seize, secure, clear, destroy etc. … The task is defined in military publications that address terms and graphics.

Concise. Orders are usually issued under tight time constraints. They also require the receiving unit to take action in a short period of time. The commander will hinder execution if his order reads like War and Peace. The application of a standard format reduces excess verbiage by disciplining the authors to stick to a designated script. There still remains the opportunity for verbosity. This must be avoided. The purpose of the order is not florid description, but clear issuance of instructions within the framework of a well laid-out concept of operations. On the other hand, the author should not bulletize the narrative. Complete sentences enhance comprehension.

We’ve come a long way from Julius Caesar personally directing his army against Vercingetorix at Alesia in 52 BC. Caesar had to fight in two directions at once and his personal presence on the battlefield influenced the battle at several key moments. Today, we have Tommy Franks sitting in Qatar as his Army attacks on two axes into Iraq effectively double enveloping Bagdad. The commanders on the front were battalion and brigade commanders, not army commanders and the order that launched the offensive was issued to senior commanders who plucked out the relevant portions to issue to their subordinates within their own orders.

An effective order lends structure to the fight, communicates the commande’s intent and vision, and serves as a roadmap to victory. A poorly written order leads to poor execution and victory becomes a matter of luck rather than skill. Given the lethality of today’s weapon systems, luck is not a preferred method.

REVIEW

In this article, we wanted to set the conditions for the rest of the series. We provided you with a brief discussion of the evolution of the OPORD. We also focused on the types of combat orders and the characteristics of a good OPORD. Along the way, we threw in some historical examples (good and bad) and we will conclude with a basic 5-Paragraph format from World War II. We believe this month’s discussion sets you up nicely for the rest of the mini-series.

NEXT MONTH

We will get into far greater detail in our next article. We will dissect the OPORD and provide our thoughts on what should go into a functioning 5-Paragraph OPORD. Our focus will be on the battalion level and below. To whet your appetite for next month, we will offer the 1940 US OPORD format. It is the one that drove many a successful Allied Operation.

1940 OPERATIONS ORDER FORMAT

GENERAL FORM FOR A COMPLETE WRITTEN FIELD ORDER

Issuing unit

Place of issue

Date and hour of issue

FO

Maps: (Those needed for an understanding of the order.)

1. INFORMATION—Include appropriate information covering:

a. Enemy.–Composition, disposition, location, movements, strength; identifications; capabilities. Refer to intelligence summary or report when issued.

b. Friendly forces.–Missions or operations, and locations of next higher and adjacent units; same for covering forces or elements of the command in contact; support to be provided by other forces.

2. DECISION OR MISSION.—Decision or mission; details of the plan applicable to the command as a whole and necessary for coordination.

TROOPS

(Composition of tactical components of the command, if appropriate)

3. TACTICAL MISSIONS FOR SUBORDINATE UNITS.—Specific tasks assigned to each element of the command charged with the execution of tactical duties, which are not matters of routine or covered by standing operating procedures. A separate lettered subparagraph for each element to which instructions are given.

Instructions applicable to two or more units or elements or to the entire command, which are necessary for coordination but do not properly belong in another subparagraph.

4. ADMINISTRATIVE MATTERS.—Instructions to tactical units concerning supply, evacuation, and traffic details which are required for the operation (unless covered by standing operating procedure or administrative orders; in the latter case, reference will be made to the administrative order).

5. SIGNAL COMMUNICATION.

a. Orders for employment of means of signal communication not covered in standing operating procedure. Refer to signal annex or signal operation instructions, if issued.

b. Command posts and axes of signal communication.—Initial locations for unit and next subordinate units; time of opening, tentative subsequent locations when appropriate. Other places to which messages may be sent.

Authentication

Annexes (listed):

Distribution:

READ NEXT MONTH’S ARTICLE—THAT’S AN ORDER!

This was an excellent article, especially beneficial for someone such as myself, that’s unfamiliar with the mechanics of a staff.