Shadow of the Sword: A Marine’s Journey – Jeremiah Workman Interview

On December 23, 2004, in the Iraqi city of Fallujah, then-Corporal Jeremiah Workman led a squad of U.S. Marines into an enemy-occupied building where other Marines had been cut off and isolated. For hours, he and his men made repeated attacks under heavy fire. Three Marines died that day, including two of those they were trying to rescue. Workman personally dragged one wounded man to safety as a sniper’s bullets ricocheted off the street.

For his actions, he was awarded the Navy Cross and was told his commander had recommended him for the Medal of Honor. Everyone would say Jeremiah Workman was an American hero.

{default}Everyone except Jeremiah Workman.

Wracked by survivor’s guilt and suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) after returning home, he ran up a $3,000 bar tab self-medicating with alcohol. He fought frequently with his wife and engaged in self-destructive behavior that culminated in a suicide attempt.

He’s not alone. In 2008, the U.S. Marine Corps reported 22 confirmed and suspected post-deployment suicides and eight in-theater, plus 13 more among Marines with no deployment history; an additional 146 suicides were attempted. For the first time, this rate of 19.5 per 100,000 nearly equaled the civilian suicide rate of 19.9 per 100,000. Marine suicide rates in 2002, the last year before deployment to the Mideast began, were 23 known and suspected, or 12.5 per 100,000. Other military branches are also reporting a similar rise in suicides and suicide attempts.

It is, Workman says, "The eight-thousand-mile sniper shot."

It is, Workman says, "The eight-thousand-mile sniper shot."

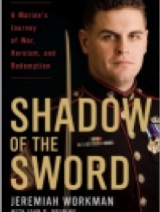

After confronting his own demons, Workman now is a public speaker about PTSD and a consultant to the Marines Corps’ suicide prevention program. With his writing collaborator, John R. Bruning, he tells his story in Shadow of the Sword: A Marine’s Journey of War, Heroism, and Redemption, a soul-searing, nothing-held-back memoir due for publication by Presidio Press in September 2009.

On September 1, Jeremiah Workman, now a staff sergeant serving with the Wounded Warrior Regiment at Quantico, Virginia, talked in an exclusive interview with ArmchairGeneral.com.

ArmchairGeneral.com: Thank you for talking with us, Sgt. Workman. People called you a hero for your actions in Fallujah. You received the Navy Cross. You saved men’s lives. Why would you feel guilty?

Staff Sergeant Jeremiah Workman: We don’t consider ourselves heroes. You always feel like you could have done more. You talk to guys who have received the Medal of Honor, and even they will say that they felt they could have done more. As a squad leader, you want to take your people over there and bring them back alive.

ACG: Your memoir doesn’t seem to hold anything back, and you aren’t always a likeable character in it. In effect, you’re putting yourself in the line of fire again. Why did you decide to go public with your story?

JW: A lot of people are asking me about PTSD. I felt embarrassed, felt like I was hiding something. One day a reporter asked me for an interview for the Washington Post. I didn’t want to do it, but I went home and thought about it, and I decided I’m going to put this out there. Once it’s out there I don’t have to feel ashamed anymore. I don’t have to hide what I’m feeling anymore.

ACG: How have your Marine brothers reacted to you putting this problem out in front of the entire world?

JW: I’ve gotten nothing but positive feedback. It’s a huge stigma, especially in the Marine Corps because of our manly image. But a lot of senior Marines, enlisted and officers, have come up to me and said, "What you’re doing is going to help a lot of guys and gals."

ACG: Many people have scoffed at PTSD, perhaps thinking it shows a "lack of morale fiber," to use a term the British Army applied to World War I veterans suffering emotionally from the effects of combat. What do you say to those who doubt this is a "real" disorder?

JW: It’s kinda weird, but in June, our family went on a vacation to Disneyland. My sister-in-law, a senior in high school, said to me, "There’s no such thing as PTSD."

I asked her, "What about a woman who’s been raped and suffers trauma from it?" She said, "That’s different." But it isn’t.

For most naysayers, their experience with trauma is going through a haunted house on Halloween. They haven’t been in combat or had a traumatic experience in their lives. In the Corps, a lot of people won’t admit to having PTSD, but they won’t say it doesn’t exist either.

ACG: Do you think part of the public may resist the idea that our warriors, the people who protect us, aren’t superhuman?

JW: I don’t think Americans send us over there thinking we’re superhuman. This kind of trauma has happened in every war, it’s just been called by different names. Americans know we are susceptible to this kind of injury because they’ve seen it in other wars. I just never thought it would be me who was affected.

I think America as a whole looks past mental injuries and just thinks about physical injuries. People don’t send their child to war and think, "I hope he doesn’t come back with PTSD." They’re hoping the child doesn’t come back with shrapnel or gunshot wounds.

ACG: Depression, which goes hand-in-hand with PTSD, was long viewed as a sign of weakness, but a respected professor of psychiatry, Dr. Aaron Beck, has stated that it is most likely to strike self-reliant people who are used to depending on themselves to achieve their goals when they fail or suffer a loss they can’t fix. (Aaron T. Beck, Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders, Plume Publishing, 1979). Were you one of those self-reliant people prior to joining the Corps?

JW: Yeah, I think that’s why people are so surprised when they read my story. People who knew me when I was growing up knew I was an achiever. I played four sports a year; I was the homecoming king. I thought I had life right where I wanted it.

I hadn’t thought about it before, that people who are used to achieving might be more susceptible to depression, but now that you say that, I can see where it would be true. Some of us are just not used to failure.

ACG: This seems to present a Catch-22 for the military, then. All military training is necessarily designed to create extremely self-reliant individuals, yet that same self-reliance may increase service personnel’s chances for post-combat depression and even suicide. Is there a solution to this dichotomy?

JW: I don’t know if I have an answer off the top of my head. We’re taught failure is not an option. But when you go to combat, you’re always going to have some level of failure, whether it’s some guy losing equipment on patrol because he didn’t secure it properly or having men injured or killed. That’s a tough question. That’s how war has always been, the way the service has always been. But that’s a good point about the training. It could be setting people up for PTSD.

ACG: What advice do you give to returning veterans regarding signs of PTSD and coping with it?

JW: You have to really look at yourself in the mirror and be honest with yourself. You don’t just come home and say, "I have PTSD." You have to watch for the signs. You start spending money, drinking a lot.

Don’t fail to get help because you’re embarrassed or you’re afraid you won’t be promoted, because it’s not just you – it affects your family.

That’s why I wrote the book. I’m a respected Marine who got help. Others can look at this and realize they’re not alone. People with PTSD think they are the only ones who feel like this. If you nip it in the bud when you get home and don’t internalize it like most of us do, that dog doesn’t have to have puppies, so to speak.

It’s like any other injury; catch it early, you can get counseling, talk it through and not have to go through all the turmoil and medication – or so I’ve been told. For so long I knew something was wrong with me, but not what it was.

ACG: In your book, you berate popular media such as movies and TV programs for showing vets as dangerous psychos, but you also describe a burst of anger in which you choked a neighbor’s Rottweiler into unconsciousness after it bit you. Do you fear that may feed the psycho-vet image?

JW: You know, looking back, (that passage) doesn’t help the situation. That was a period when I had hit rock bottom, when I was lost in a really, really dark place. I’d just been relieved from duty as a drill instructor. (Workman had a breakdown in front of men he was training and was sent home on leave – Ed.)

The Vietnam guys are the ones who really got the bad psycho image applied to them, and I think it’s unfair.

ACG: You point out in the book that PTSD isn’t limited to combat veterans. Any traumatic event, such as the death of a spouse or child can trigger it. Do you think your story may help people outside the community of veterans who are suffering PTSD?

JW: Oh, yeah. When we first sat down to work on this project, that was one of my big things. I didn’t want this to be just for veterans. If you lose a family member, if you’re a victim of rape or some other violent crime – anyone who reads this book, if they haven’t sought help, it will encourage them to go get that help if they need it.

ACG: Thanks again for talking with us. Is there anything you’d like to add?

JW: Let people know they’re not alone out there. Keep your head up, keep marching, and you’ll get through it. There are a lot of people out there who care about you, whether in the service or out.

Editor’s Note: Every branch of the U.S. military has established suicide prevention programs. Click on the service branch below to visit its Website on the subject.

I am trying to contact Jeremiah Workman in reference to a Rally in Washington DC on July 25, 2011. I am interested to see if he would like to take part in this. Is there any way I can get an email address to contact him or a phone number.

Thank you