No Retreat: The Russian Front – Boardgame Review

No Retreat: The Russian Front. Boardgame. Publisher, GMT Games 2011. Designer, Carl Paradis. $60.00

No Retreat: The Russian Front. Boardgame. Publisher, GMT Games 2011. Designer, Carl Paradis. $60.00

Passed Inspection: Outstanding physical components, interactive combat system, little downtime.

Failed Basic: Numerous errors in rule book, scripted play, no production system, "counterblows" are confusing.

No Retreat is a two-player, grand-strategic, WWII Russian Front hex-based boardgame, with army-sized units (80,000 to 210,000 men) and two-month game turns. The game is GMT’s release of Victory Point Games’ (VPG) 2008 No Retreat (including the scenario-modules of "Na Berlin!" and "No Surrender"), given a deluxe makeover, GMT-style.

{default}The game’s notable characteristic is its simplicity. VPG is known for small-format games with high-quality components; designer Carl Paradis keeps true to that without abusing GMT’s larger budget. The map has oversized hexes (1 1/16"), soft pastel colors, and a matte (non-glare) surface. The large counters (3/4") are double thick and have simple graphics (NATO symbols, although optional counters include armored vehicles’ profiles), making them easy to read and to pick up.

This is a game with extremely low unit density. Most of the scenarios will likely not have more than 40 units in total on the map at any one time: the entire German army is 25 units at most, with the Russians being not much more. And there always seem to be counters missing. For example, during 1942, nearing the time of the Germans’ deepest penetration, they may only have four units south of Moscow, and the Russians perhaps as many as five. After the large games of the past, this reviewer welcomes the easy-to-manage low density, however. The small number of counters is more than made up for by the clever design, which is intended to constantly produce uncertainty and to keep each player busy during the entire turn.

The Components

Victory Point Games have outstanding components and graphics, but GMT surpasses even those. This deluxe version includes a standard size, mounted mapboard (22"x34"), in eight folding panels. It comes, elegantly enough, in its own zip-lock bag, but the fit is tight and using the bag too often may not be practical. The map is itself elegant and simple, utilizing cool pastels to differentiate open terrain, swamps, mountains, and rivers. The matte finish means there won’t be much glare, a factor almost all other designers ignore in order to have a literally glossy-looking map. The graphics do not overwhelm and, with the large hexes and counters, players can focus on strategy and tactics without having to move counters to see the terrain.

Most unit counters feature large type and only two bits of information, the standard attack/defense and movement factors. Some have their attack value printed in white, indicating a limited attack capability. Almost all are back-printed with a second step value. The German units always have two step losses; the Russians phase those in. At first, Russian counters can take only a single step loss, with their strength represented by the weaker side of the counter; then, as units upgrade they still take just a single step loss, but use the stronger side of the counter. Finally, near the end of the game, Russian units are full two-step-loss units.

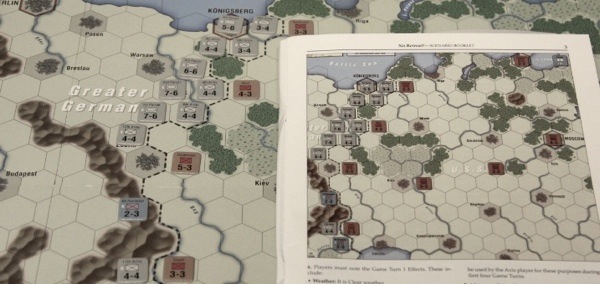

Setup is easy; just use the picture provided.

Each of the 55 cards has two events, one for the Russians and the other for the Germans. During play, some cards are limited, e.g., some only have effect in years other than 1945, others depend on which force has the initiative, etc. The cards also become a form of currency. They can be played for their stated event but also can be used to buy units, make additional attacks, or to allow strategic movement. Don’t think of this as a card-driven game, however. The cards may provide important tactical advantages (such as giving two units two extra movement points) but rarely dictate overall strategy.

The game has two booklets: 24 pages of rules and a scenario/notes book. The rules are mostly clear, but also contain a surprising number of errors such as incorrect rule references and unclear or misused terms. You should download the latest living rules from GMT’s Website to get the latest edition, which makes some corrections. Otherwise, the books are easy to read, are in color, and provide copious and detailed play examples. The first two turns are covered and provide ample insight, rules clarification, and hints about play.

Game Play

There are six scenarios (Barbarossa, Fall Blau, Operation Saturn, Operation Citadel, Operation Bagration, and Na Berlin [On To Berlin!]), plus a campaign game and a tournament scenario. Each scenario is usually four to six turns long, commonly considered an evening’s play, and each has its own victory conditions; in some you may earn an automatic victory by capturing objective hexes. An interesting aspect is that each scenario can be used as a starting point to the campaign game. In that case, just ignore the scenario victory conditions. You don’t even have to decide this when you start the scenario. I wish more games had this feature.

Some players claim they can finish the campaign game in a long evening—it takes me three sessions—but the campaign is at most 28 turns and can be won in several different ways, including Sudden Death. At the end of every three turns, the side with the initiative can win if it has more victory points than the amount shown on the turn track for instant victory that turn. That means you check as early as turn three. The required points are high for a sudden-death victory that early in the game, of course, but not impossible. In fact, there is a detailed example of play covering a German attempt to end the game on turn three.

Your first impression of the rules will likely be that this is a standard game straight out of the 1970s or ’80s and isn’t going to be much fun for experienced players. It has the familiar I-go-you-go sequence, standard zones of control, step losses, two-factor unit strengths, and a ratio-based combat results table (CRT) including a 3:2 column. The game comes with a scripted feel. There is no production—new units come in according to a schedule—and events occur on specific game turns, as does the switch of initiative.

But first impressions mislead. The combat section provides two important twists.

The phasing player has to declare all the hexes he plans to attack that turn, after which the non-phasing player is allowed to announce his own attacks—called counterblows—but must also designate the hexes that will be attacked. The attacker can resolve the combats in any order, as long as all combat hexes announced by both sides get attacked. This clever mechanism means the attacker can never precisely plan an attack phase. The counterblows are usually not free. It costs one card to specify each hex (some card events allow you to place additional counterblows), up to a maximum of five hexes. Often, a counterblow is a long-odds situation for the non-phasing player (e.g., 1:3) but is not always foolhardy. It can be used to weaken one of the phasing player’s attacks or to seize an opportunity to do some additional damage.

The second twist is that the CRT provides one of the most interactive combat systems I’ve encountered. Some results are standard, such as Exchange (both lose a step), Retreat (retreat two hexes, with elimination if unable to do so), and Shattered (retreat two hexes, then remove the units, but they come back next turn), and Destroyed (which removes one step, but most Russian units are only one step). The potential results that set this combat system apart are the Counterblow (the phasing player places a free counterblow marker on one of his own unit’s hexes so as to force an attack next turn) and Counterattack (allowing the other player to optionally attack back immediately). Counterattack results can go on indefinitely.

Each player has a different CRT. The Russian’s emphasizes exchanges while the German’s is heavy with retreat results. From among the six results, you get a diverse set of situations sure to keep each player planning. Gaining ground is done more through combat than through the movement phase. Most retreats are two hexes, and victorious units also advance two, with armor sometimes getting three hexes. ZOCs do not restrict advances.

Paradis himself notes that reading and understanding those rules may be tricky at first (something I can agree with, as a lot of the time during the first playing was spent re-reading the counterblow/counterattack rules). However, using those concepts maximally is critical in the game.

Solitaire

The game also comes with a solitaire version, downloadable from the VPG site but with a password that comes inside the game box. This version doesn’t provide a new artificial intelligence guideline; you are still expected to play both sides fairly. Instead, it encourages fair play by adding the possibility of having to change sides! The print and play set comes with 12 new cards. During the normal Sudden Death checks, the card drawn might have you change sides outright or to change if you’re within the indicated number of Sudden Death points (typically one to four points). Thus, an otherwise runaway victory becomes a mess you have to clean up. "Fuhrer Directive," which puts additional victory points on certain locations, ensures you’re always pushing the armies.

Summary

No Retreat plays surprisingly well. The scenarios have a high replay value. The different victory conditions allow players options; combined with the cards, this mean tactics change with each game. Automatic victories almost always seem within reach. In some cases, the temptation to go for that kind of win is high—but if you don’t pull it off, your units will be in a very vulnerable or inferior position.

The best part is that these mechanisms prevent downtime. Each player has considerable options in combat phases (which should occupy much of the time), but even during movement, cards may be played interactively. The low unit density changes the time focus from the movement phase to the combat phase, a more interesting part, anyhow. There are enough other options through card play, unit replacements, non-standard units, and the combat results that players have all the critical decisions of a large game, in a shorter and more manageable package.

Armchair General rating: 83.

Solitaire rating: 3 out of 5; 5 out of 5 with the separate solitaire game system.

About the Author

Robert Delwood is a long-time board gamer and author. Between Saturday nights, he writes software in Houston, Texas, that, among other things, makes sure the astronauts have clean underwear every day. Mundane, but they appreciate it.

I’ve been playing this game for almost a year. I’m loving it.

Thanks for reviewing my little game (first design ever). It’s very appreciated.