Confederate Boys and Peter Monkeys

(Adapted from a talk given to the Geological Society of America on March 25, 2004.

See the following link)

It is difficult for young men who are not able to handle a musket on the field to participate in Civil War reenactments. These young men are too old to stay in the camp with their mothers, and too young to march out on the field. It is hard for them to find first person roles to play in speaking to spectators. For Southerners, however, one role young men can play is that of “Peter Monkey.†This little known occupation among southern boys was an important, although often overlooked, aid to the men at the front.Â

During the American Civil War, the blockade of southern ports by the Union Navy prevented the importation of gunpowder into the Confederacy. Without gunpowder, the muskets wouldn’t go bang and the Yankees wouldn’t fall down. So, to fight, gunpowder was one of the more important materials that was needed. Thus, the Confederacy needed to manufacture gunpowder. Lots of it.Â

{default}Gunpowder (a. k. a. blackpowder) is made from the following three items: potassium nitrate (about 75%), charcoal (approximately 15%), and sulfur (about 10%). The potassium nitrate, also known as “saltpeter,†is the oxygen producer of the compound, whereas the charcoal is the combustible agent. The sulfur makes the powder readily inflammable and forms, on burning, potassium (K) or sodium (Na) sulphide which prevents some of the CO2 from forming K or Na carbonate (which would reduce the amount of gas and pressure). The sulfur produces a rapid burn, because strictly speaking, blackpowder burns and does not explode, and it was used in the cannon and muskets of both armies during the American Civil War. Charcoal is made of charred wood, and is easy to come by. Sulfur comes from a number of sources, and was fairly plentiful in the south. Potassium nitrate, however, was more difficult to find, and a special agency, called the Confederate Mining and Nitre Bureau (a.k.a. Confederate Niter Bureau; Confederate Nitrate and Mining Bureau, etc.) was formed to find sources of potassium nitrate. Nitrate was taken from dead horses and cows, the floors of tobacco barns, and from night soil (urine and excrement- see the Appendix).

Another way of getting potassium nitrate was from cave dirt.

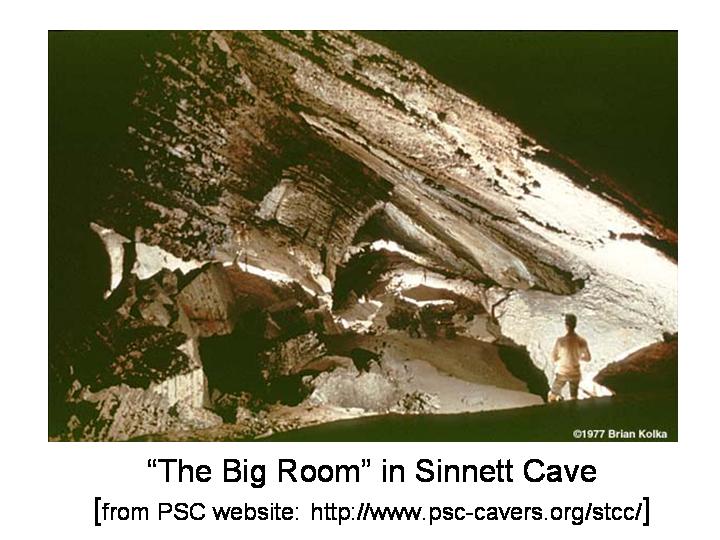

To see how difficult it was to get potassium nitrate from cave soil, we took some samples from two caves. The first cave the Sinnett-Thorn Mountain Cave System near Moyers, West Virginia. The second cave was Organ Cave, near Ronceverte, West Virginia. Both cave systems were mined by the Confederacy during the war, and we wanted to see how effective were their methods of nitrate production.Â

Map of the Sinnett-Thorn Mountain Cave System (from Swezey et al., 2004, A Guide to the Geology of the Sinnett-Thorn Mountain Cave System: The Potomac Caver, v. 47, p. 3-14). (Click on images to enlarge).

Sinnett Cave is privately owned, and we needed written permission both to explore the cave, and to take the samples of dirt. Each endeavor has it’s own rules of conduct. For example, reenacting has the non-farb rules of using only accurate period clothing and equipment. Likewise, caving has its own rules. The rules for caving are that one should never go caving alone; each person must carry at least three light sources; and that the caves should be undisturbed as much as possible. The states of Virginia and West Virginia have very strict laws that prohibit defacing caves or disturbing cave environments, etc. By law, even taking small samples of dirt requires written permission of the cave owner.

After we got the samples, we followed an account of Confederate nitrate production techniques (Powers, 1981 and Eller, 1981). Some chemistry comes into play here, so pay attention. First, the dirt was placed in large bins shaped like the letter “Vâ€. At the bottom of the bin was a slit, and beneath this slit was a trough that led to a larger trough or bucket. The bin would be filled with cave dirt, and then water would be poured slowly over the dirt. As the water percolated though the soil, calcium carbonate and nitrate would come with it. The water would then drip through the slit at the bottom of the bin, and be captured in the troughs or buckets arranged to collect the muddy water. In chemical terms, the cave soil plus water resulted in ions in solution “[calcium nitrate + calcium carbonate] + water à calcium, nitrate, and carbonate ions in solution.â€Â

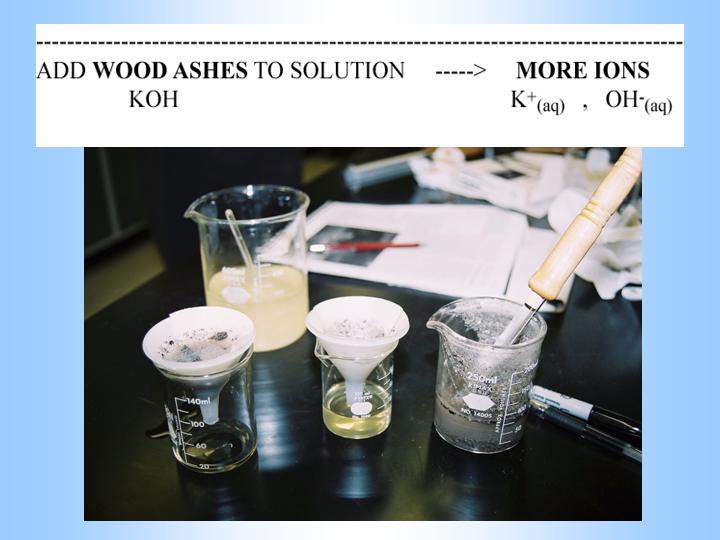

To get potassium ions in solution, the Confederate manufacturers added wood ashes to the leached solution from the cave dirt. Potassium is present in all trees, but is more prevalent in hard woods. Traditionally, willow has been preferred, but almost any wood will do. By adding water to the wood ashes, potassium hydroxide would dissolve into potassium and hydroxide ions in solution. Â

Getting the potassium from wood ashes needed for gunpowder.

Mixing the water from the cave dirt and the water from the wood ashes, resulted in calcium, nitrate, carbonate, potassium, and hydroxide. From this mixture, a precipitate would form, which was called “curds†by the miners. The curds were calcium hydroxide and calcium carbonate. What was left in solution were the ions of nitrate and potassium. The evaporation of the solution resulted in the precipitation of the nitrate and potassium ion as K2NO3 (saltpeter).Â

So, what does all of this mean? The process is pretty easy, and requires only a few crude instruments and procedures. The soil and water need to be close together. The wooden bins are easy to make. Large iron kettles used to evaporate the water were fairly common and easy to obtain. The only thing that was in short supply was the manpower to mine the dirt.Â

This mining was fairly easy to do, as it was “in-your-face†mining, in that the dirt was dug out at face level, and it was easier than hard rock mining. Cave dirt mining does not require a great deal of experience, as there is little blasting, drilling, or other specialized mine engineering needed. One simply gets to the dirt and starts digging.Â

At Sinnett Cave, the miners climbed up to the “Big Room,†where the dirt was dug, and then dumped down a natural opening or chimney nearer to the entrance. There the dirt would be gathered at ground level into bags, and taken to the front of the cave where the water was. The bags often may have weighed as much as fifty pounds each.

[continued on nextpage]

Pages: 1 2

I noticed you have no comments posted so I thought I should let

you know how much I appreciiated reading this. Marion Smith did

an article on Trinity Nitre Cave and it included the name of my

great-great-grandfather on the payrolls, and I bought his book

also. I live only a few minutes from where he worked and that has

been an amazing discovery for us. I am sharing your article with

my relatives who are participating in our genealogy research,

and your article gives insight into what it was like foim. The year

conscription up to age 40 was made law was the year he went to

work in the cave.

I was about six weeks past my eleventh birthday when John Salling died in my hometown in 1959. I was just beginning a life-long interest in the Civil War. There is much debate about John’s age still today, but for me this lays to rest any debate about his service. I recently found in the OR the directive allowing the hiring of “free persons of color” to work the cave sites. Could you further elaborate on use of “boys under conscription age” ?

Reportedly, Sallings’ father was one of his great-grandmother’s slaves. His mother, was her white grand-daughter. Technically, he could have been considered a “free-person of color.” In an interview shortly before his death, he claimed to recall helping bury his great-grandmother in 1862, so he was a big enough boy to do that. In the same interview he said he only collected dirt from under houses and outbuildings and never worked in the caves.

Thanks for the article.

Glenn

John Salling is my husband’s great great great Grandfather. Thanks for the article and the comment above has helped me try to figure out who his father is. Very helpful!