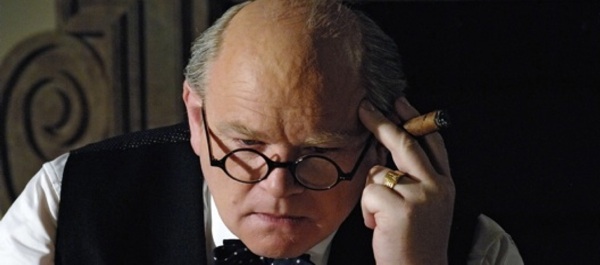

Brendan Gleeson as Winston Churchill in ‘Into the Storm’ – An Interview

Historical dramas are about what happens when people, ordinary people, get into what the Chinese call ‘interesting times’.

On May 31, 2009, at 9 pm Eastern Time, Into the Storm premiers on HBO.This historic drama depicts Sir Winston Churchill during World War II, when he served as Britain’s prime minister. Veteran actor Brendan Gleeson portrays the complex, often contradictory prime minister. Gleeson’s extraordinary career has seen him cast in such diverse roles as Hamish Campbell in 1995’s Braveheart, Walter "Monk" McGinn in Gangs of New York, and Professor Alastor "Mad-Eye" Moody in the Harry Potter films. He was nominated for a Golden Globe award for his portrayal of the hit man Ken in 2008’s In Bruges. Recently, he spoke with ArmchairGeneral.com in an exclusive interview about his career, about portraying Churchill, and about his own grandfather, a member of the Connaught Rangers in World War I. Into the Storm is presented by HBO Films in association with BBC, a Scott Free production and a Rainmark Films production of a film by Thaddeus O’Sullivan; written by Hugh Whitemore.

{default}ArmchairGeneral.com: Your film career contains an interesting mix of character-driven historical dramas along with films heavy with special effects, like the Harry Potter movies, Beowulf, and Mission: Impossible II. Do the two genres place different demands on you as an actor?

Brendan Gleeson: Yeah, I tend to search out variety as much as I can. I try not to do rubbish, number 1, but I do try to take on one project a year that has real artistic merit and is a real artistic challenge. When that’s done, I can go do something fun like Harry Potter. I try to not to get over-grim about it. I think the movie business needs to remember that we need to entertain people.

ACG: What is it that attracts you to history-based films?

BG: There’s a very interesting thing that happens to an actor in terms of historical projects. In any film the huge challenge is to make people believe something happened. If you do a historical film and do it with integrity, you don’t have to convince them this is real. They know it’s already happened.

Historical dramas are about what happens when people, ordinary people, get into what the Chinese call "interesting times," and we see how they react. As an actor, you can’t be the real person, but that’s where imagination becomes important, to show how they might have felt, how they might have reacted.

ACG: In particular, what appealed to you or challenged you about playing Winston Churchill?

BG: He’s such a complex individual. His resilience and self-belief and facing down a situation so much greater than he was at the time—his ability to make people realize they were more than they thought they were.

Coming from my background (growing up in Ireland), I was aware of what it was like to sit across from him at the table. He was very tough, very bullish while negotiating Irish freedom. So for me it was interesting to sit on his side of the table for awhile.

A lady once said, when you first meet Winston you’re aware of all of his faults and you spend the rest of your life discovering his virtues. The longer I portrayed him, the more I saw his virtues.

ACG: In Ireland, feelings toward Churchill might charitably be called mixed, if not outright hostile. Did you find any irony in being asked to portray the Briton who played a key role in negotiating the treaty with Sinn Fein regarding Irish freedom in the 1920s?

BG: It was a definite factor. I had to deal with that baggage. Nevertheless, what he did in the Second World War was remarkable. His maverick qualities, his self-confidence appealed to me. It would be interesting to see how he would be remembered if he had failed.

You know what he gained from the disaster at Gallipoli in the First World War? That what was wrong was that he was only second in command. He needed to be in charge. His conviction that he knew exactly what to do was incredible. I don’t think anyone else could have galvanized his people as he did. Really, circumstances have a large part to play in how a man can rise to destiny.

I’m in no way churlish about it. My grandfather was in the First World War and he was captured by Turks, but he wasn’t at Gallipoli.

ACG: What unit was your grandfather with?

BG: He fought with the Connaught Rangers. They’re an interesting group. In India, there was a mutiny among them (in 1920) because of what was happening in Ireland. Grandfather said that if he had been in India at the time, he wouldn’t have joined the mutineers because he had given his oath (as a soldier). He was proud of his war record.

ACG: There’s one memorable scene in which Churchill grabs a helmet during an air raid and goes onto the roof of 10 Downing Street to watch the bombing. His wife, in a shelter, remarks that he sometimes seems like a little boy playing at war and suddenly it has come true for him. What were you thinking during that scene on the roof? What were you hoping to convey about him?

ACG: There’s one memorable scene in which Churchill grabs a helmet during an air raid and goes onto the roof of 10 Downing Street to watch the bombing. His wife, in a shelter, remarks that he sometimes seems like a little boy playing at war and suddenly it has come true for him. What were you thinking during that scene on the roof? What were you hoping to convey about him?

BG: Funny thing is, I like the fact you don’t know what he’s thinking. That whole thing about playing at war—you know, I’ve thought about his relationship to war. He really was a warmonger at times. He was a warrior. He said, "War which was once cruel and magnificent has now become cruel and squalid."

I feel he didn’t take war less than seriously, but he was fascinated from the time he was a child with war and the glory of war. He didn’t just send men to war, he was willing to put himself into it, in the Boer War for example. (As shown in the film, Churchill intended to personally go ashore with the Normandy invasion force. – ACG) He wanted to do great deeds, and he saw war as a way to elevate himself to great position where he could do them.

When he’s out there watching the bombing of his city, I think he has a feeling of being truly appalled and truly alive, and he felt could do something about (the war and Hitler). This is his job, this is what he felt he was born to do. I think he pictured himself as a knight.

War was always savage, it’s not a new thing. I think in my generation we’ve forgotten we have to overcome our sense of survival in order to face danger for some larger cause.

ACG: In early scenes, Churchill is shown standing up to Lord Halifax, who is urging a compromise with the Germans in order to save the British Expeditionary Force in France. Churchill adamantly refuses. At this stage of the war, did that contribute to his reputation as a warmonger?

BG: I think he already had the image. He was very warlike; he was Lord of the Admiralty. He looked for ways to fight. He thrived in it. A lot of people did not like him. He even changed political parties then changed back. But what he had was this conviction Hitler was a real danger. He’d said that throughout the Thirties, and people were tired of hearing it—but he was able to say, I was right.

When the burglar comes through the house, that’s when you want to make sure you’ve got the Rottweiler. I think the mood of the country was to go at this guy (Hitler), so I don’t think calling Churchill a warmonger was a negative thing at that time in Britain.

ACG: People today, Americans especially, tend to forget what a near-run thing it was for Britain standing alone against Nazi Germany in 1940. There are scenes in the film in which Churchill seems unshakably confident and others when he is gripped by what he called his "black dog of despair." Would you care to comment on those two sides of his personality?

BG: I think they were inextricably linked. One of his most admirable traits was that he refused to lay under the black dog. He’d paint, he’d build a wall, he wouldn’t give in to it. The self-belief was something he needed.

ACG: Churchill didn’t have a close relationship with his parents, something touched on in this film.

BG: He adored his parents. There was a feeling from a very early age that he wasn’t the center, like a dunce put in the corner but who knows the answer. He knew he wasn’t in line to inherit Blenheim Castle, a huge estate (Churchill’s birthplace – ACG). He’d been slightly in second place for much of his life, and that allowed him to see the center from outside, so when he got to the center he was able to say, this is why I am here.

You know Churchill was both British and American. (His mother was American—ACG) There are different views between the British and Americans toward failure. Americans don’t like failure. The British tend to admire people who do their best, even if they fail. His reaction was much more American. He did not settle for it. He didn’t want the heroic failure. The greatest gift he gave the British people was to tell them "we will not surrender." Even if driven from the island, they would set up a government elsewhere, perhaps in America or Canada, and even if it took a thousand years, they would reclaim England. He took surrender off the agenda, and that freed people up a bit. There was no feeling that if we talk to them maybe they won’t throw the stones at us as hard. By taking away the option of surrender, he took that out of consideration.

ACG: How would you sum up your experience playing Winston?

BG: Slalom without a ski lift. You’ve got to walk up the mountain, but it’s well worth the ride down.

ACG: Is there anything you hope viewers will take away about Churchill after watching Into the Storm?

BG: His humanity. I’m an actor, not a historian. I would hope we would sit in his shoes for a little bit and share the amazing kind of life he had at that time.

Read an interview with Hugh Whitemore, who wrote the script for Into the Storm. Click here to read an article about Churchill’s unconventional mother.

“Shalom [sic] without a ski lift. ” It seems likely that Mr. Gleeson actually said “slalom” at this point.

[thanks for the catch! — Ed.]

I know that I’m a bit late to comment, but I just saw this remarkable programme last night. The interview was very interesting, however I think there’s one piece of information about Brendan Gleeson that will expand upon something he says.

Gleeson’s first major role was actually another tv programme on an historical figure, Gen. Michael Collins in “The Treaty”. What is truly ironic about him also playing Churchill was that Collins was responsible for negotiating a new Irish Free State and it was Churchill that was the main bulldog on the British side, fighting the proposal tooth and nail. So when he says “coming from my background” I think he means not just as an Irishman, but as one who played a man whose reputation and life was dealt a fatal blow by Churchill’s doggedness.

He said it’s funny how Americans forget how England stood up to the Nazis. Maybe he should remember how the Irish never stood up to the Nazis, actually let them roam around and go to school in Ireland.

And if England didn’t declare war against Germany cause they attacked Poland, whom England never helped, but actually sold out, then they wouldn’t have been in that mess.

bit of personal memory:

monsignor shannon (of wealthy Irish lineage) of st.thomas apostle catholic parish,( serving University of Chicago neighborhood’s arriviste yankee- irish gentry) entered the classroom of us 13 yr olds to ask a show of hands – “how many of your parents support germany against england?”. all hands up.

this, before pearl harbor. the well-bred msgr. shannon then launched a war of his own, to right our teenaged heads to defeat nazi millenial blood-lust. the monsignor single-handedly turned hundreds of feckless irish-american louts into fighting irish yanks- at Leyte Gulf, Mindanao, The Bulge, my 3 eager uncles among them,

…

Msgr himself a hero of sorts.

Unpopular at first, but then respected, after we beat Shickelgruber. (Chicago took in a large migration of slavic Poles, camp survivors., and oddly, mostly litterati…people of superior mentation).

A man of full discretion, he met weekly (Thurs. afternoons at 4, had the maid turn down the bed, then gave her and the young sacristan the half-day off)—with the wife of pres, of Hyde Park Bank. The maid was my relative.

The Monsignor never made bishop, so he just faded away to a wealthier far-off suburb after the war. But the pious women of St Thomas Apostle parish had only kind words of him in his wake- for at least 50 yrs….my grandmother, my mother, and surely the banker’s wife.